Alex writes about a specific scene in Last Action Hero, because a podcast apparently wasn’t enough.

I get annoyed when people on podcasts mention a subject briefly and then say things like, “Oh we’ll get to that later,” before promptly ignoring the subject for the rest of the conversation. (I’m sure there are some who get similarly annoyed with essays that start with three consecutive sentences beginning with the word “I.”) I don’t quite know why this bothers me – it happens in casual conversation pretty much every day of my life – but it does. It makes the podcaster in question sound like the subject in Room 237 promising to Photoshop Stanley Kubrick’s face over the clouds in The Shining. So in an effort to avoid becoming that which I proclaim to hate, I must add an addendum to our recent Last Action Hero podcast.

When James and I discussed Last Action Hero, we were on a bit of a time crunch due to technological issues and the existence of the Buffalo Bills. During the podcast, I mentioned the jaw-dropping scene when Jack Slater and that shithead kid arrive at a premiere for a movie about Slater himself, before saying that we would move on, promising to return to the subject later. I said “But we’ll get back to that.” We did not get back to that. The podcast ended, I realized my error, but James had to flee the country. So here I am.

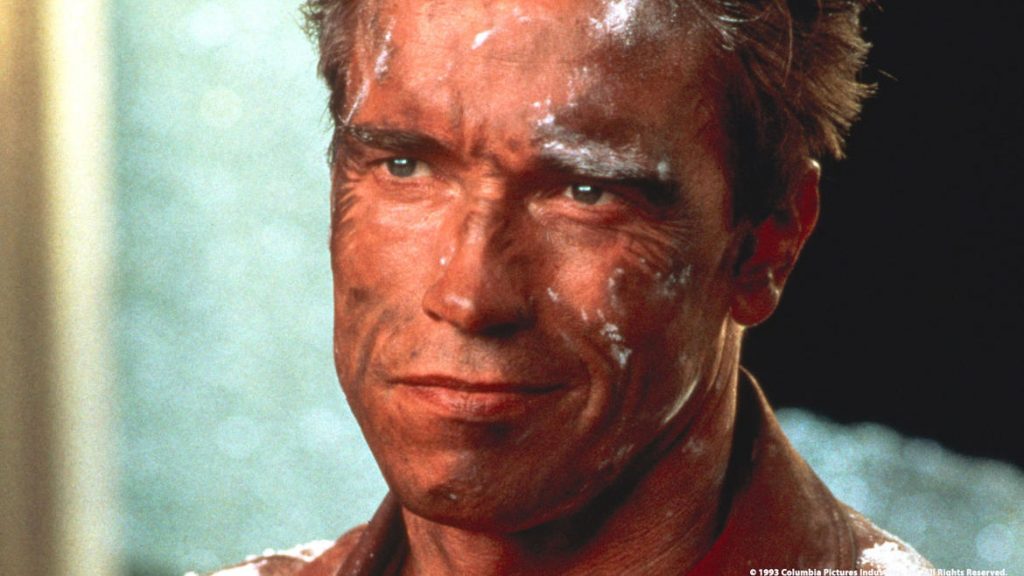

Watching Last Action Hero again, I remain a touch surprised I didn’t expect Slater to end up at a premiere for his own film in the third act, because once that idiot child returns to the real world with Slater, it seems like the most logical place to go in this overlong, postmodernist tale of hubris. Seeing Arnold Schwarzenegger playing himself was something I definitely expected to see over the course of this film, but seeing Arnie put his arm around his (then-)wife Maria Shriver deeply surprised me. This was 1993, and such things didn’t happen. Something about Shriver being brought along for the ride allowed for an added layer of self-awareness, especially once she delivers a couple lines painting her as somebody who is deeply annoyed by how frequently her husband talks about Planet Hollywood. Then Arnie proceeds to give a red carpet interview that is legitimately funny and self-reflexive.

“We kill less people in this movie,” Arnie tells Chris Connelly, the man who would eventually help kill Grantland. “In this movie we only kill forty-eight people, compared to the last one where we kill a hundred and nineteen.” Like had been talked about so frequently in the press, Arnie was owning up to the extravagances of his own movie, and doing so in his most extravagant movie to date.

If there is one missed opportunity that Last Action Hero skirted past, it is the concept of the destruction the action hero leaves in his wake. There are touches of it – talking about how Slater has no contact with his ex-wife, that there is always somebody in the closet of his apartment trying to kill him – as well as a deeply honest moment as the villain Benedict enters the real world and realizes there is much less of an effective police presence here than he is used to. (Original screenwriters Zak Penn and Adam Leff built their script around this concept of the action hero having to deal with consequences for said action until it got micromanaged to shit.) But we got to that on the podcast.

There is a simple reason this premiere scene speaks to me more than any other in Last Action Hero: it is a scene of deconstruction, and my brain has been molded by deconstructionists. Like so many of my generation, Charlie Kauffman and Quentin Tarantino scripts morphed my brain, and I am thusly very aware of anything that’s a little too set up without being acknowledged as an obvious construction. The 1990s are the decade when these things flipped. In the past, postmodernism and self-reflexivity existed, but in the 1990s explicitly toying with predictable formulae became more popularly accepted. It was the decade where David Foster Wallace reached the highest level of popularity, and David Foster Wallace was a man who never wrote a sentence without immediately deconstructing it.

Similarly, the process of watching a movie can mean traveling through a metaphorical minefield of my own (not so total) recall. When I watch a movie, I can never simply focus in on the story, and it has been many years since that has been a possibility. One of the oft-repeated discussions from our earlier podcast episodes was that James would describe how as a youth he watched movies as novels committed to screen, barely paying attention to cinematic grammar. I’m sure I did that as a child, but by the time I was eighteen I was very aware of the effect technical choices had on my appreciation (or lack thereof) of a media product. Outside of that, I am also so aware of the constructions of the filmmaking industry that I rarely get to sit in a movie theatre without being aware of what lead the Digital Cinema Package I’m watching projected onto the screen. Seeing Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri makes me think of how much warmer Martin McDonagh’s previous film In Bruges looked in comparison, and the effect the industry’s collective transition to digital cinematography and projection had on my Three Billboards experience.

Then there’s Lady Bird, a movie I felt lacked connective tissue, which lead me to think about Boyhood, a movie that I thought used a lack of connective tissue to accentuate the feeling of this whole movie being a collection of memories Mason was cycling through in the final scene. I wondered if I was giving Richard Linklater too much credit for that idea, just like I wondered if I was giving Greta Gerwig too little simply because I have less experience with her work as a director (given that Lady Bird was her first solo directorial effort). These thoughts occur while I’m watching the film in question, and I have no way to quell them. Who the fuck knows what I, Tonya is going to make me think of when I eventually see it, but judging by the trailer all these thoughts are going to be multiplied by thirty.

Does this sound exhausting? Yes? Good. Because it is.

There’s another portion to the Last Action Hero premiere scene that I adore. After Ripper stages an attack on the real Arnie, Slater rushes in to save the day before rushing back out of the premiere to chase Ripper. The real Arnie, however, chases him, leading to a thoroughly impressive special effect – these two Arnies in 1993 look better than the two Armies in 2010’s The Social Network – and an intriguing exchange of dialogue.

Arnie: “You know, you’re the best celebrity lookalike I’ve ever seen… Hey, if you get to Los Angeles, call my office. We can get you shopping centre openings…”

Slater: “Look, I don’t really like you, alright? You’ve brought me nothing but pain.”

The scene does not cut back to Arnie after this line is delivered – Slater immediately dashes out, leaving the quote unquote real version of Arnie in the metaphorical dust. The real is nothing but an annoyance at this point. To put too much critical analysis into a movie that its own director says had an absurdly short post-production process is silly, but it is telling that there is no return to the real Arnie’s perspective. We don’t get to see how he feels about what Slater said to him, because the real Arnie no longer matters. He’s brought nothing but pain.

James asked me on the podcast if I felt like Last Action Hero was ahead of its time, and I felt uncomfortable saying “yes,” mostly because so little of Last Action Hero was designed by artistic thought, instead dominated by capitalistic desires. Seemingly every decision was driven in some capacity by Arnie’s own producerial desires – from replacing Penn & Leff’s thoughts on violence with more casually self-reflexive zingers to the way Arnie’s hair was coiffed on the poster – because in the early 1990s the star of the movie was what mattered most. The advertising for Last Action Hero was so out of control that an ad was sent into space, and the production was so rushed that said ad was sent to space months after the release of the picture itself. All of these things lead to critics teeing up to talk shit about this movie in a way that is (a touch) unfair and (for sure) unwarranted, but it was the 1990s and Hollywood had yet to figure out how to throw money at the screen until the reviews came in positive.

When that dumbass kid gets transported into Slater’s world, said transportation happens inside a gigantic, one screen cinema. Outside the cinema (and I believe inside as well, and Frank mentions it as well), there are signs explaining that the kindly projectionist Frank’s one screen cinema will soon become a ten-screen Loew’s multiplex. One room for collective focus will soon be replaced by ten rooms containing different genres, different mentalities, different movies. Some of them will be more formulaic than Last Action Hero, some of them will be more adventurous, some of them will be similarly genre-mashed messes meant to capitalize on what corporations have decided is currently cool. The only thing that will seem real is the existence of all these different, bizarre thought processes coming together in a way that we no longer find bizarre. Everything will happen all at once, and we will become accustomed to this without really thinking about why.

Recently I asked James if he would be accepting of trying to do podcasts on more foreign films. I wasn’t thinking about this at the time, but I’m sure this has something to do with wanting to be able to experience a story with fewer of these constructions that I like to throw back in my own face. I know less about Andrei Tarkovsky and Aleksandr Kaydanovskiy than John McTiernan and Arnold Schwarzenegger, so talking about Stalker is less of a loaded experience. If the goal of this podcast is to learn something about myself – which it quietly is, as that’s the only real reason I can explain my obsession with films in any sort of vaguely intelligent way – it will theoretically be easier to learn when certain elements are stripped away.

Would I go back to a day before I started thinking about all these things entirely? No. I don’t want to live in The Matrix any more than I have to. So much of my cinematic appreciation is built around the fact that knowing these things makes me feel smart, that I understand the thoughts going through these auteurs’ heads, that the decision to use a dolly here makes me feel like I know this unknowable auteur slightly better than those around me. Again, this sounds exhausting only because it is.

I want to get closer to reality, because I know these cinematic constructions aren’t real. Reality is what I need, but I still need my reality to come through a screen, because the actual version of reality I thought existed becomes more difficult to grasp with each passing day.

Can we get back to a point before the Last Action Hero premiere scene? We can’t get back to that.