Alex attempts to write about the work of Terrence Malick in a non-idiotic way. (He fails.)

There are many things said about Terrence Malick’s work, and most of these things are nauseatingly oft repeated. He doesn’t care about structure, his films are boring wannabe philosophy classes on the nature of being human, and they feature endless scenes of people running their fingers through grass. Characters keep feeling walls for no reason. All of these things are true, and yet Malick’s movies are tremendous.

My first exposure to Malick came when I watched The New World in the dark basement of my parents’ home, while I was between apartments. Since I had not yet figured out that I shouldn’t lie down on a couch while watching movies, I fell asleep soon after Christian Bale entered the picture. I loved the first half of the movie, but for some reason was not compelled to rewind the rest when I awoke to a DVD menu screen. I continued on with my life, as one does.

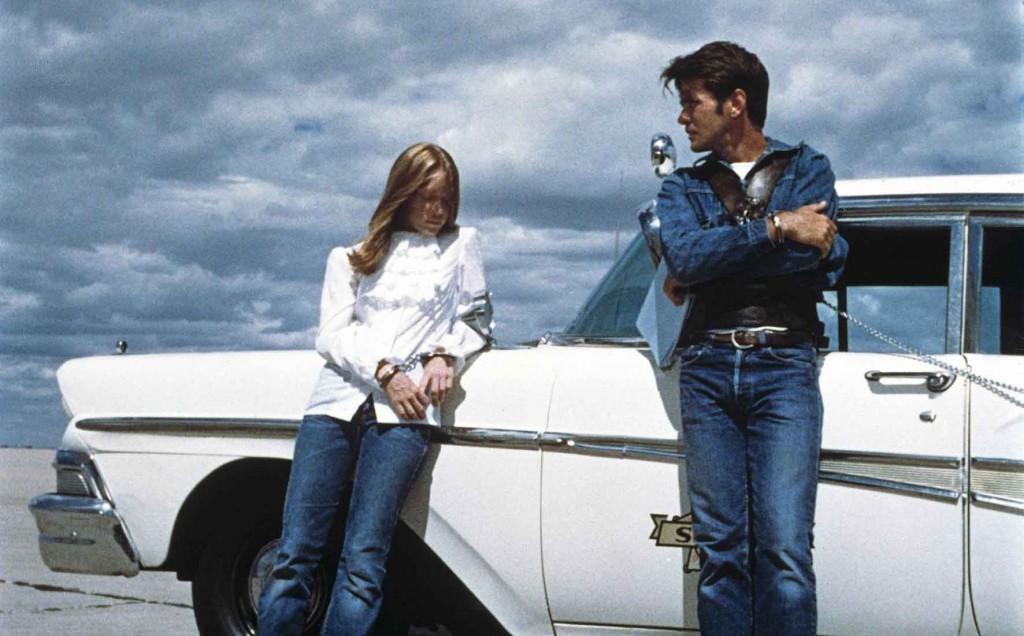

Badlands was up next a few weeks later, on the main floor of the apartment I had since moved into. Despite not loving my first foray into his world, the grasp of Malick’s promise remained firm. I did not fall asleep, because I had no furniture and had yet to acquire anything I could comfortably lie down on. Again, I enjoyed the first half, but by the time Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek were visiting some dude named Cato, I had checked out and begun writing about it to a far-flung friend instead.

About a week later, I watched The Thin Red Line in the top floor of that same apartment. It was an exceedingly warm apartment in the summer, so all the windows on the small upper floor were open. A cross breeze and the sounds of birds flying around carried through the living room for the duration of the movie, as I sat in my newly acquired movie watching chair. I realized that this was the perfect way to watch these movies that capture the feeling of the natural world: with elements of the natural world surrounding you as you watch it.

Earlier today, I saw Knight of Cups in a movie theatre, and the experience was just like seeing any later Malick work. Myself and a number of others in the theatre clearly loved it, some people were stymied by it, and at least five people straight up walked out. As I left the theatre, though, I was hit with a different version of the same feeling I had over ten years ago when watching The Thin Red Line for the first time. Routinely ignored sounds were a little bit clearer to me and – upon leaving the theatre – I noticed details in the downtown world that I would never pay attention to otherwise. Malick’s unreality had given me a firmer grasp on my own reality.

This is the core problem of Terrence Malick’s work: you almost always sound like an overly pretentious idiot when you’re talking about it. You write endless preambles about your attachment to it, trying to make the films sound intelligent, and yet it all still makes you sound like an idiot.

As I was sitting down to write what is in front of you now, I wondered to myself why it has taken me so long to write about one of my favourite directors, and then I realized it is because I prefer to avoid sounding like a dummy whenever possible. Malick’s talk of nature and the philosophical verse that peppers his work never makes you sound like a logical person when removed from the context of the film. And yet, here we are, because this is where Malick brought us.

“There is the way of the wind, and the way of the rain. They will guide us, guide us through it all.”

“There is the way of the wind, and the way of the rain. They will guide us, guide us through it all.”

Malick’s career begins with Badlands, his contribution to the Hollywood Renaissance movement, and as such his debut features all the tropes we have come to see as attached to a 1970s movie commenting on the 1950s. Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek literally burn down the latter’s family home, and taking the ideas of the Greatest Generation with it. Sheen’s character Kit explicitly models himself after James Dean, not unlike Jean-Paul Belmondo’s fascination with Bogart in Breathless. Even Kit and Holly’s meeting plays out very similarly to Bonnie & Clyde’s introduction in the Arthur Penn classic that jumpstarted this specific cinematic movement.

Time has proven Badlands to be Malick’s least-Malickian work, mostly because he was still working out the kinks. More than any of his other movies, Badlands feels like it could have been made by somebody else. But the ingredients were there, weaving their way into the fabric of the film, like Spacek’s rushed voiceovers throughout. The voiceovers sounded a bit rushed, and there was less improvisation than usual, but they would be further discovered in time.

Malick really leaned into his impressionistic tendencies in his next film, Days of Heaven. In order to maintain shooting in natural light whenever possible, characters were often backlit in a way that would become one of his trademarks. Many key ideas in the film would be communicated via voiceover, another one of the newfound Malick staples. Much of the film’s dialogue was even scrapped in the editing room so that Malick could replace it with Linda Manz’s voiceover.

The film itself is simplistic but good and, like the rest of Malick’s work, you can find as much in the movie as you’re willing to look for. As Richard Gere and Sam Shepard politely spar over the hand of Brooke Adams, the working class quarrels with the rich once again. Gere accidentally murders his boss at a Chicago mill in the prologue, though, and that sense of pending dread hangs over the film, compounded by Shepard’s terminal illness. We see the movie through the eyes of Manz’s character Linda, the younger sister of Gere, who provides voiceover about the nature of the world in connection with all the things that are happening around her, all the influences on her existence. The movie ends up being a meditation in how there’s good in everybody and evil in them all the same, half devil and half angel found within us all.

And then came the hiatus of immortality. Malick perfected his naturalistic style just in time to leave it behind for two full decades.

“Father. Son. Sun. Clouds. Forever approaching, forever challenging us.”

Malick left Hollywood for decades, for reasons that remain unclear. He had a carte blanche production deal in place after Days of Heaven, and he worked on a variety of screenplays after that film’s completion, but it seems he never deemed any of it to be worth following through on. Regardless, he left Hollywood, moving to Paris to teach, write screenplays, and do some Heidegger translations. Maybe he preferred to spend his time simply frolicking in various ponds, listening to Carl Orff and touching leaves, talking about the wonder surrounding him. This is the unending mystery of Malick, the mystery of a man perpetually asking questions of the world while steadfastly refusing to answer any of ours.

Malick doesn’t seem to want us to know anything about him at all. When he eventually returned to filmmaking, he started writing in his contracts that his image not be used to promote the film, and as such there are not many modern pictures available of him. Malick is so able to blend into the fabric of existence that, in 2012, TMZ released a video of Benicio Del Toro walking to his car with an unnamed pal, and TMZ initially didn’t realize that the pal in question was actually Terrence Malick. (After the Internet informed TMZ who the schlubby-looking dude walking with Del Toro was, they changed the clip to this.) Malick never wants to be seen and for some reason perhaps that lead him to not want to shoot images of his own.

For a couple of decades, anyway.

“Nobody’s home. Principles don’t exist, merely circumstance. Treat us, treat this world, as it asks of us.”

Eventually though, Malick came back, turning his roving Steadicam and endless whisper monologues to the horrors of war. The film that marked his return, The Thin Red Line, works as an interesting comparison to Saving Private Ryan, with the latter released only a handful of months before the former. While Steven Spielberg’s film is immaculately directed in its own right, it uses a focus on combat and its results to make war seem like a thing that leaves a physical toll on its participants, a toll that is best exemplified by intestines hanging out of their stomach. In Malick’s version, though, he shows more characters but less violence, instead choosing to show the effect war has on their own inner dialogue about the world. The Thin Red Line isn’t as much about the fear of death as the fear of what war has done to our world. There is no clear-cut main character; I can think of a solid argument for at least five of the characters, and a hypothetical sixth once you realize Adrien Brody was mostly cut out of the movie in post.

The finished version of his follow-up, The New World, came together in the editing room once again, this time with Malick continuing to recut the film even after its initial theatrical release. The eventual film combined The Thin Red Line’s pondering about the human effect of war (and in this case, colonization) with the conflicting status of the working class explorer John Smith and Christian Bale’s rich, come-along-after-the-tough-part John Rolfe. It was Days of Heaven all over again, this time with Q’orianka Kilcher’s Pocahontas replacing Brooke Adams’ Abby. And this time, The New World had more of a focus on what factors created the world its viewers were still living in today. In the film we see the characters building the world in the way it would eventually become: filled with fighting, and nobody particularly caring what happens to the natural world along the way. It comfortably functions as an allegory about the United States’ occupation of Iraq, regardless of whether or not Malick intended it as such. It shows us a world crushed by our own good intentions.

“My memories of you are the memory of a world, a world I couldn’t grasp. Reach to me, and we will reach together.”

There are, fundamentally, three different stages of Malick’s career. His American New Wave films showed a man figuring out his place in the world of filmmaking, fumbling about with old tropes in new, gorgeous ways. His first two post-recluse films were about notable times in American history, and the reverberations those events have had on the modern world and its inhabitants. And then, Malick began to point the camera inward, as he began his most explicitly autobiographical films.

The Tree of Life is clearly about Malick’s relationship with his parents; the problematic one he shared with his father, and the more accepting, nurturing relationship he had with his mother. To The Wonder is another film about a Malickian Love Triangle of Everlasting Indecision, as a man is pulled by a variety of options around him, ever refusing to settle on one of them for fear of giving up what could come with the other. And Knight of Cups is about a man questioning whether or not the career path he has chosen for himself is one of merit.

In each these three films, there is a consistent visual idea that is hit on repeatedly throughout their respective run times. The Tree of Life is shot almost entirely from the perspective of a child, with a constantly roaming camera that never seems to be shooting from higher than a child’s eye level. In To The Wonder, we see Malick’s interest in casting normal people pushed to its furthest. He had always cast non-actors – think the workers in Days of Heaven and the Polynesians in The Thin Red Line – but in To The Wonder it seemed like he and Javier Bardem spent days walking the streets of Bartlesville talking to the population of their set. We got more of that in Knight of Cups, as Wes Bentley’s wayward brother (almost certainly inspired by Bentley’s own struggles with addiction) talks to the homeless of Los Angeles, and as Cate Blanchett’s doctor treats the perpetually afflicted.

As we learned more about Malick through his later movies, it put his earlier ones through a different lens. It’s easier to see Badlands about him meeting his wife as they were younger and first began a relationship, just like it’s easy to see him re-meeting her after a couple marriages as Rachel McAdams in To The Wonder. But what this all boils down to is mere hypothesis. I am searching for the Sasquatch, pontificating about mere possibility. The core appeal of Malick, and mysterious artists in general, is the core idea of the auteur theory. We feel that by looking at the collected work of these artists, we can better understand the people that make them by seeing the trends that connect the pieces. But it’s all just guesswork. We have to watch from afar, always wanting to be so much closer.

“Know me. Know me like we can never know that which shines above.”

I wrote this whole big spiel about Malick’s entire career. This piece used to be – I kid you not – 7000 words longer than what you’re reading now. I sat down, I wrote, I wrote, I wrote, and then I wrote again for the next three days. I wrote about Malick’s whole career, about the trends that continue from movie to movie to movie, and I honed it all as if it were a piece about Malick as an auteur, from the Hollywood Renaissance to the modern Greek patron phase. A real ‘womb to tomb’ sort of deal.

And it was all a slog. It was impossible to get through.

So I saw Knight of Cups again, I wrote specifically about that movie, and then I mercilessly cut down the mumbling insanity that was the essay to that point. Basically, I did what Malick did in his own editing phase. Trying to write about Malick in a critical capacity finally made me discover just how impossible it is to really get to the heart of his work. He tries to exhaust all of his options, and then he figures out what he really wants with all the pieces he has given himself only when it gets to a point where he can do nothing else. At some point, he has to decide what it is he wants to get across; at some point he has to deliver a finished film. And only then is he going to settle on what it is he’s willing to give to the world.

The auteur theory is basically another reason of wanting to know a celebrity better. It’s no different than following Kim Kardashian’s every move, in this case you’re merely following a person’s moves that have more artistic merit. Somebody that loves Ms. Kardashian does so specifically because they want to know her, or they want to believe they are interesting in the way they find her interesting. This is the core of my own approach to David Fincher, or Cormac McCarthy, or Terrence Malick. I respond so strongly to some of their work that I feel like they must have the answers to my questions, so I want to believe I can lob those questions their way and get an answer in return.

For obvious reasons, this is foolish.

I understand Malick’s limitations, and I am often engaging in conversations about them. His female characters are almost exclusively archetypical and boring. There are a surprising number of instances of adults dating fifteen-year-olds in his filmography. These are old problems; even for members of the American New Wave, some of their tendencies are now decidedly old world. But every filmmaker has their limitations, and Malick knows this too. He is still constantly finding new ways to create beauty because he never stops trying to find them among us.

My rough work is not typically anywhere near as rough as this piece looks to me right now. There were a hilarious number of spare notes strewn everywhere throughout the first version of this essay, many of which have barely been cleaned up here. If Malick prefers to revel in messiness, it only makes sense I do the same, as I try to make sense of his mess.

I am not the only person with such goals. For a director who is now so brazenly uncommercial, Malick has influenced a bunch of people that have made a shitload of money. Every Christopher Nolan movie from Memento on has dabbled heavily in the world of Malick, specifically in Nolan’s use of cutaways and voiceovers. The Revenant and Birdman are Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu’s tributes to Malick, right down to the supposed environmentalist leanings of the former. Ridley Scott’s Gladiator was able to win the Best Picture Oscar because The Thin Red Line emotionally prepared the common viewer for all that grass-feeling the year previous. Written by future auteur superstar Quentin Tarantino, Tony Scott’s True Romance is basically a reboot of Badlands, right down to Hans Zimmer’s Carl Orff-infected score. The better films in David Gordon Green’s filmography are widely known to be imitation Malick. Even the indie hit of three summers ago, Jordan Vogt-Roberts’ The Kings of Summer, was created specifically as a Terrence Malick movie for idiots. Malick’s style is impenetrable, but it is not wholly irreplicable.

“The speed of the world is not ours to choose. It is our duty to navigate, not dictate.”

The quotes interspersed throughout this piece are fake. I wrote them as imitation Malick, and I wrote them very quickly. I assume they read as silly, just like they probably read as appropriately Malickian. It’s not difficult to temporarily capture the feel of Malick’s work, but it’s borderline impossible to keep it going for the duration of a film. It’s the everlasting contradiction of Malick: his films are silly, the words said in them are silly, and yet they all coalescence to form something tremendous. Malick sees the rambling forward movement of life and – especially as he ages – he leans right the fuck into it. He is truly one of a kind.

I never have a particularly strong reading on Terrence Malick’s work. I know what they’re about, sure, but I never feel confident in that. There are fewer details to hang my critical hat on, fewer certainties because of it. Typically, I find his movies thematically simplistic, but delivered in such a unique way that they seem much more profound than they are on paper. I don’t think Malick himself would deny this. His on-set process now seems to be to show up with a camera, a small crew, some actors, and some cue cards to play with, eventually shaping the results together through an uncommonly long editing process. This strategy was never going to lend itself to tightly–honed work, and as such Knight of Cups makes even The Thin Red Line look as staunchly structured as Network. But I don’t find this lack of a strong, core idea to be problematic in the least. Malick is so obviously searching for something that can never be found, and so as long as the search is gorgeous I don’t care if its results aren’t profound.

And again, the contradictions of Malick appreciation become clear: you can make up nonsensical bullshit like in the paragraph above to defend pretty much anybody you want to make into an auteur. I could probably come up with something similar about Zack Snyder, if I liked his films enough to actively want to engage with them. I am a talented bullshit artist, and even The Guardians of Ga’Hoole can’t hold me back there. But I’m confident time will prove me right with Malick: any time an artist is doing something in a new way, it doesn’t necessarily make sense in the time it is released within, and whether or not we like Malick’s work, he’s pretty much incomparable at this point. Whether or not we see it doesn’t matter, because that’s not what Malick is really trying to do. He doesn’t care if we see what he’s doing, because he’s too busy trying to figure out what others see.

Malick shot Knight of Cups in 2012, and it first hit the festival circuit last year. He shot Weightless in 2012 as well, and I have no idea when I’ll get to see that. Assuming Weightless isn’t the last arrow in Malick’s metaphorical quiver, he will probably die with an unfinished movie. I would guess he’ll want to shoot something else post-Weightless, and hopefully he will be given the money necessary to do that. But as a 72-year-old man, even he understands that he could potentially greet death before he is able to settle on a final cut. Somebody will finish that hypothetical movie – likely a cavalcade of his editors and producers, perhaps with some notes from Jack Fisk – and it will probably be good enough. It will pale in comparison to his earlier work; it will be his Pale King. It will be his final statement, kind of, but Malick has never been good at finality. He specifically makes movies that accept there is no ending but death. To The Wonder ends with the idea that a metaphorical heaven has left us behind, and in Malick’s first four movies, the main characters die. The Tree of Life ends in a not so subtly conveyed idea that everybody we have met is gathering for a super boring desert rave in heaven. But in each film, the movie closes with shots of the natural world continuing on without them, as it will when you die.

Throughout Knight of Cups, there are two constants. People seem to be swimming constantly, and when they’re not swimming they’re looking upward, in the direction of anything that could fly above them. Late in the film there’s even a quick edit that goes from Christian Bale in the water to Bale looking upward as birds fly above. The two are directly linked; above and below the ground are barely different. There’s still a little devil and angel in us all, residing just above or just below the surface. More than ever before, Malick wants to show everything. He wants to show Bale from birth to death, but he doesn’t necessarily want us to know that’s what he’s doing.

As the movie progresses, we see Bale go from spending pretty much all of his time inside Los Angeles to beginning to reach outward. He first ventures to Las Vegas, then to various places that do not necessarily seem to be a part of any city, really. Some new school Tibetan monk and his garden, or in a very suburban home, with his very suburban (probably dreamt) life with Natalie Portman. There are trips back to Los Angeles, but they all seem to be in flashback, as Rick goes from wondering why he is here to questioning why he was there in the first place.

The desert remains another constant in the film, featuring prominently in both the beginning and the ending. Perhaps the whole movie exists with Rick walking through the desert of the mind, pondering his choices to that point, and figuring out what his choices will be going forward. But one thing is clear: Rick starts in nothing, and ends in nothing, willing to begin anew.

The last line in Knight of Cups is “Begin,” and Malick knows that’s the best one can hope for at any portion of their life. They can begin as children, hopefully ones who aren’t too damaged over time by Brian Denehy or Brad Pitt’s tough love. They can begin anew in middle age, leaving their world of Hollywood fakery behind for the ducats of a Greek patron. And they can finally begin as they accept death, seeing the world as it will be without them: exactly the same as it was with them in it.

I have had Malick’s films playing in my office all week. Not necessarily to be focused on, just kind of in the background while I write what you are almost finished reading. Not unlike after I saw Knight of Cups, I can feel a difference in the world I’m in. I can more clearly hear the light rain falling on the roof next door to me, and the sound of the wind coming from my television seems to blend perfectly with the breeze blowing through the window eight feet from it. Even my keyboard strokes sound more beautiful with the effect of the Malick filter. He makes elements that are worth your focus, but are also totally comfortable with fading into the background. He lives among us like we live with his films. His films about transients are transient themselves.

If the point of art is to allow you to see the world around you in a different way, then Malick is making art. He’s doing it in a new way, and that’s often messy and confounding, but what’s not confusing is the elevated feel his work creates. If it stays with you that must count for something and – more than a lot of his peers – Malick’s work maintains in my mind.

I am not doing a great job of explaining all of this. I know that. I am describing something indescribable, discussing tone poems with sentences that are trying to sound cogent and slightly academic. These two worlds should not be able to co-exist. Malick makes films entirely out of emotion, and I try to lead a life of logic. This is why I would be fascinated to pick his brain, to see the other side of the coin I can’t seem to fully flip. But the mystery will remain, because it is unreasonable to expect otherwise.

This is close enough for now.