Alex talks about Vince Staples, True Detective, history, and perception.

“This is how I see it. Good luck.” –Vince Staples, on NPR’s Microphone Check

I am not unique in this, but I will be more up front about it than most: every time I write something, I am writing because there is something in my own life that I feel could use deciphering. This is always painfully obvious, if only because I occasionally use the pronoun “I” up to five times in a single sentence. I see a movie where Rashida Jones perfectly reflects exactly every problem I have, and then I write about it through the guise of mediocre film criticism. Criticism is always biography, and I don’t see a way around it.

Again, these are not new thoughts. They are pervasive, and they are true.

And yet, I spend a lot of time thinking about media products that could never possibly reflect my lifestyle, people seem to think. Movies about relationships and books about false idols are easy to understand; we have all culturally decided that those are art forms that are meant to be taken metaphorically. Music is taken that way, too, so long as that music is not made by people who are rapping. Rap music is always taken literally for some erroneous reason; perhaps there are so many lyrics in a given J. Cole song that they can’t possibly mean anything other than the literal meaning of the words. Which is insane – by that logic, a David Robert Mitchell script can only be about a specter that follows youths, as opposed to the way the specters of your youth follow you into adulthood. A Taylor Swift song is assumed to not literally be about blood that shouldn’t be transfused, because that would be bananas.

This is the fundamental reason why any white kid in high school before the mid-2000s* would be met with confused glances: how can this suburban white kid identify with this music that does not reflect his existence in any way? “You don’t care about boats, snowmobiles, nor skis, and your memory is impeccable,” one would say. “Your arson career is non-existent. There is nothing in Forgot About Dre that applies to you.”

*I haven’t been a high school student in a long time, but I strongly suspect nobody gets made fun of for listening to rap anymore.

Admittedly, this unheard conversation has helped many terrible rappers further the idiotic claims they make in their music. We take everything Fetty Wap says literally, which helps him seem tougher than he actually is, despite the fact that it means we’ll never take Trap Queen as interesting. I strongly suspect this is exactly what he wants, because Fetty Wap is an awful, uncreative rapper, and looking for meaning in his music is a failing pursuit. He makes music for listening to exclusively while complaining about the state of modern music. And he’s part of the cavalcade of terrible artists ruining it for the people that actually make interesting, thoughtful music. He’s ruining it for Vince Staples.

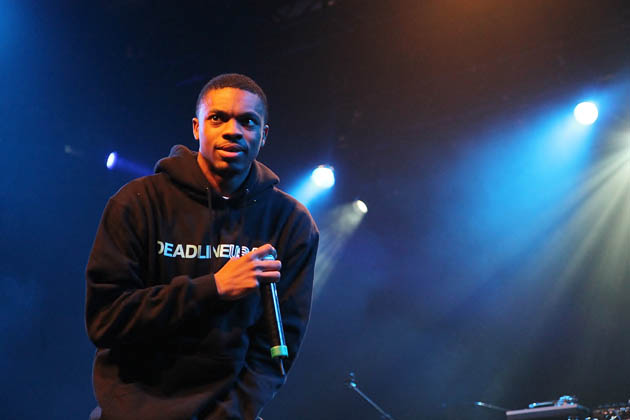

Vince Staples’ new album Summertime ’06 is tremendous. Pretty much everything about it is great. The 22 year-old Staples is an incredibly modern rapper, bouncing forever fluidly in and around the beat, but he is so skilled at it that – in contrast to other young, modern rappers – it never feels messy. It always seems like there is a plan within the mystery, and the mystery never fails to be catchy. Norf Norf’s menacing groove makes it impossible to resist giving into at least a light shoulder shimmy. Jump Off the Roof is so beautiful it makes me think that maybe I should try it. If Vince Staples were David Morse in True Detective, I would join his cult immediately.

The guy behind the guy of this record is producer No ID, a hip-hop quasi-legend whose biography tends to lead off telling you about how he played the role of mentor to Kanye West’s manatee. Originating in Chicago, No ID played a prominent role in Common’s early career, producing the vast majority of Lonnie Lynn’s pre-Soulquarians output. No ID has since produced myriad songs you know by myriad people you know, from Jay Z to Rihanna to Nas to Ed Sheeran to Drake, and has worked closely with Kanye West since 808s & Heartbreaks*. Weirdly, it’s difficult to find much about No ID as a person – he has been a prominent producer in hip-hop for two decades and yet I am having immeasurable trouble even locating his precise age. The chronology of his Wikipedia article begins in 1997, despite the fact that three years prior to that he had produced a classic hip-hop record. He somehow seems both forgotten and omnipresent. But if we are to assume No ID is the same age as Common, then No ID is a nearly middle-aged man working with a wunderkind in a genre that emphasizes the importance of the latter and ostracizes the former. The mere fact that he is able to play such a role in a distinctly modern record like Summertime ’06 says more about hip-hop history than a Fetty Wap song ever could.

*No ID has mostly been relegated to “additional production by” credits post-My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, but with Kanye that likely means No ID did more than the credit might indicate.

Frequent No ID collaborator Jay Z’s most prominent influence on the genre has been a simple, but under-discussed one: now, a rapper is permitted to age gracefully. By first retiring, Jay Z signaled that he believed rapping was a young man’s game, which was still the overwhelming perception when he did so. Sean Carter was exiting the ages that are generally considered an athlete’s prime, so this legend had his jersey lifted into the rafters of Madison Square Garden. But then he got bored. Running a label wasn’t for him, and making the best song on a middling Memphis Bleek record wasn’t enough to fill that void. So Jay Z came back, and simultaneously learned and signified that in hip-hop you don’t really have to leave. The genre had aged enough that it no longer seemed impossible for real adults to make good work within it. Everybody from Kanye West to Eminem to (eventually) Drake will have to bow to Hov for allowing their careers to continue past the age of 32.

Similarly, when I was younger I always assumed I would stop caring about hip-hop somewhere in my twenties. I was conscious of the Hova Retirement Tour as it was happening, and it seemed logical. I could imagine myself as a twenty-nine year old giving Road to the Riches one last spin before I rode off into the sunset. Rap music just seemed like something that would evaporate with my youth. But this has not happened, and assuming it doesn’t happen in the next ten months I will be missing this self-imposed deadline. This is the other thing Jay Z’s refusal to retire has enforced: it is totally possible that hip-hop fandom will endure with people for the entirety of their lives. It is conceivable that I will one day be in a nursing home, talking about Run-DMC’s stylistic importance right up until I die. Hip-hop is officially a part of North American existence, and we are finally (mostly) accepting of that.

Thanks, Obama.

When a (whatever books are called in 2073) is (whatever the word for ‘written’ is in 2073) about one hundred years of hip-hop, the election of President Obama will be seen as the moment that hip-hop truly crossed over into mass culture, because there is no element of mass culture bigger than the presidency. Dan Charnas’ The Big Payback, a tremendous book about the history of the business of hip-hop, uses the moment as concluding proof that hip-hop was finally accepted by a majority, and he’s not wrong. Barry Obamz never shied away from the fact that he liked hip-hop, and much of his support relied on rappers encouraging young voters to make their voices heard. Obama referenced a Jay Z song during his first presidential campaign, and people collectively shit their dicks. Had George H.W. Bush mentioned LL Cool J at any point in his campaign, Michael Dukakis might have been the 41st president. That’s not to say hip-hop was engrained in all aspects of culture by 2008 – there was a fist bump exchanged between Michelle and Barack upon winning the Democratic nomination that a Detroit Fox News commentator referred to as “fisting” – and it’s still not today. But it’s a lot closer than ever, and it’s not going away. It has officially aged into adulthood, and we all know we have to at least tolerate that.

Summertime ‘06 and other like-minded records from this year are representative of an adult upheaval of sorts. They’re taking everything that has gotten hip-hop to this point and spinning it all into a bizarre abstraction that’s more aesthetically challenging than what has come before it. It’s all distinctly modern, and it all sounds like a world in upheaval. The well has been mined, and rappers are trying to put all those different pieces together to see what works. We’ve officially reached post-rap; we’re probably just around the corner from the hip-hop equivalent of Godspeed You Black Emperor.

Hip-hop has been in an experimental place since 2008, when 808s and Heartbreaks quietly allowed for emotional honesty to exist in popular hip-hop. A couple of years later, My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy and Watch the Throne were caps to an end of hip-hop’s youth: by the summer of 2011, hip-hop had officially grown up, and two of the biggest names the genre had ever produced created time capsules of the genre’s most important influences. Since then, most popular hip-hop has veered experimental, including West and Hov’s own work. Magna Carta Holy Grail isn’t very good, but it certainly doesn’t sound like an album made by a classicist. Yeezus specifically tried to tear down everything that had made Kanye the most influential artist of the past decade. And the youth inspired by these luminaries have gone even further, something that has been proven time and time again this year. Even removed from its intriguing lyrical journey, To Pimp a Butterfly is aesthetically challenging and intricate. Last year’s Run the Jewels 2 sounds like it’s trying to beat perception into a pulp. At Long Last A$AP is an uneven but mostly successful trip down the dark hallways of a party one maybe shouldn’t want to be at anymore. And Summertime ’06 is a record about a turning point that allows these doubts to exist.

Despite being shorter than most hip-hop records, Staples’ entry is designated as a double album. The first half plays as a more hopeful piece, where the overconfidence of youth trumps the word of logic, and where our hero believes jumping off a roof is not necessarily a terrible idea. But things turn in the second half; the whole record sounds dark, even the allegedly hopeful parts, but the second half still manages to sound darker. It sounds like a new phase of existence, one that happens after the person in question has figured out that things aren’t always going to turn in their favour.

Summertime ’06 turns on the almost-title track Summertime. As the repetitive plodding of the beat goes on and on, with guitar stabs of sadness occasionally joining in on the slowly evaporating fun, Staples continues repeating that this place, this unpopped balloon of a mind state could be forever, but he does so in a tone that indicates he is starting to figure out that he might be lying to himself. As tears start soaking up sweaters, Staples grasps the world he is actually in. His feelings told him that love is real, but then again feelings are known to get you killed (or at least emotionally demolished). As the song closes, Staples begs not to be left alone in this cruel, cruel, world, but the song makes it sound like he already knows he can’t avoid it. He is by himself, because figuring these things out is an entirely lonely feeling. Summertime is a song about somebody trying to hold onto something that is already gone, and as such it all sounds profoundly sad. Listening to it feels like learning the hardest lesson of your life over and over again. It is unsurprising that this song repeats perfectly into itself; you could keep it on an endless loop if you never wanted to continue past it.

But Staples knows he has to move on, so he spends the second half of the album talking about the world how he now sees it, as an adult. Innocence has been lost, intelligence gained.

What Staples and No ID have created in the studio is a cohesive, thoughtful collection of music that still sounds like it has been pieced together. The percussion gives the impression that somebody left a bunch of scrap metal and glassware around the studio and Pharrell came in to spend a day playing it all with spoons. Staples’ verses don’t feel especially tight but somehow remain perfectly controlled. The record feels orchestrated to sound like auditory confusion. Staples picks up the pieces of the genre’s past and, with the help of somebody that experienced that past first-hand, puts it all back together to form its disparate son.

Not that Vince Staples cares about that.

In a recent Grantland profile, Staples details his own history with the genre, a history that is mostly minimal. When Amos Barshad asks Staples about the effect various legends of the game have had on him, Staples’ responses are only surprising to those that haven’t listened to his album.

Didn’t you ever hear anything in rap music that you loved that affected you?

“Who was out? Name ’em, name ’em.”

Uh, the classics. Nas. Jay Z.

He cuts me off: “I’m 21 years old. 50 Cent was third grade.”

Wow. He’s right. I think some more. Jeezy?

He scoffs. “Why would I look up to Young Jeezy? ’Cause he made money? I don’t care about money. What has he ever said?”

OK then. I go back to the infallible ones. Didn’t you ever listen to Public Enemy?

“Never. I would never do that.”

N.W.A?!

“Never! I’m 21 years old. My mom was [listening to that]. Why would I listen to N.W.A if I’m not listening to my parents? Public Enemy would mean nothing to me when I was growing up. N—-s wasn’t marching in Long Beach.”

This is post-rap. Rap that is so determined on moving on from the past that it can’t even acknowledge the influence history has had on it. Rappers can age, and rap can age, but young rappers still can’t acknowledge such things, lest they prematurely age into the genre’s father figures of whom they claim disinterest. As such, modern rappers must acknowledge their job in a distinctly modern manner: as just that, a job. Staples doesn’t view himself as a professional partyer who occasionally speaks rhythmically into microphones. He is a tradesman, albeit one in an uncommon trade.

“I always treated [rapping] like it was a job,” Staples tells Barshad. “I was never late or nothing. I just didn’t care. I don’t like attention. And that’s 90 percent of why people strive to do what we do now. Attention. Or the money. Which they’ll be rudely awakened by. We don’t get no fucking money. We don’t even get to own our own songs nine times out of 10.”

Ignoring the inherent contradiction of his statements*, Staples is distinctly up front about his feelings on the industry post-Napster. Nobody makes any money in the genre, they make it from what the genre gives them access to. It’s always the step before the step. Jay Z made The Blueprint, so he got a Reebok deal and a hue of blue in 2003. 50 Cent understood this as he was capitalizing on the death rattle of the music industry’s boom: he knew owning a stake in Vitamin Water was more important than simply getting paid to endorse it**. Dr. Dre is a goddamn billionaire. And these things are all possible because of – but are not exclusively related to – hip-hop. If the actual rapping was what mattered, Rakim would be making millions selling deluxe headphones with questionable bass distribution. But it’s never about your words. It’s about what those words influence other people to say about you.

*Treating something like a job typically involves caring about the money you receive for performing your tasks. I will not deny Staples is prone to saying some very dumb things sometimes, but he is also twenty-two.

**50 has also seemingly failed as a businessman, but that doesn’t minimize the validity of the initial motives.

This is the part where I start talking about True Detective. Vince Staples would hate this part even more than what has come before it. He would say, “There is nothing in my record that should make you think of Nic Pizzolatto, except perhaps a tangential connection to Los Angeles. You’re trying too hard, and you’re not even getting paid to.” And he would be right in totality. I do not listen to Summertime ’06 and think about Ray Velcaro’s bolo tie. But when I think about how people talk about Vince Staples, it seems impossible to not think about another young-ish gun operating in a genre I adore.

Season two of True Detective has been, according to most, a failure. I do not necessarily share that opinion – although I might in a week – for reasons that are overlong and overcomplicated, and therefore unimportant here in this already overlong and overcomplicated essay. Problems exist in the show, of course: the direction is less impressive this season and the cinematography more haphazard, Vince Vaughn is definitively not pulling it off, and the show lacks a one-of-a-kind performance by an actor who was thrust into the centre of culture at exactly the right moment*. The wannabe Cormac McCarthy musings are no longer being delivered by people who will set the template for how to act on True Detective, but by performers who are now following that template a little too closely. It has gone from being a segmented, eight-hour film to a television show. These things are all true. What has mystified me most, however, is the pile of vitriol that has been directed to the show’s creator and (almost) sole writer, Nic Pizzolatto. Following a mystifyingly mythologizing profile in Vanity Fair where Pizzolatto is treated as the deity of television, it seems like critics have been waiting for any slight error to piss all over Nicky Pizz. Which he was kind enough to bestow upon them.

*This last one always seemed like it was going to be pretty difficult to replicate.

The whole Rich Cohen profile is weird, for reasons others have pointed out. Nic Pizzolatto frequently talks like one of his characters, and Cohen seems desperate to write a Pizzolattian profile of his idol. This combination somehow made everybody assume Pizzolatto is an asshole. It now does not seem difficult to imagine a world where True Detective continues to be on a creative downturn this season and next, the show is cancelled, and all its praise gets retroactively heaped on season one director Cary Fukunaga. When this happens, its failures will be pinned squarely on Pizzolatto, and this profile will encapsulate why. We gave the writer too much credit, and he believed it all.

But this is how we are to talk about showrunners now. It’s how we talked about Matthew Weiner, it’s how we talked about Vince Gilligan, and it is how we (belatedly) talked about David Simon. As premium television became a creative goldmine in the 2000s, the easiest through line for writing about a series in a critical sense was to find the closest thing to the auteur, which turns out to be the person who oversees the room of authors. The director of a film is somebody that has total creative control over their product, but in television that can’t be the case – with the compressed scheduling that comes with the medium, as a director wraps shooting an episode, they must immediately spend the next week in the edit bay while the following episode is shot. (This is what made Cary Fukunaga’s work on season one of True Detective so impressive – he did both, eight times in a row.) Regardless of the influence directors like Alan Taylor or Clark Johnson or Michelle MacLaren have on a show, the showrunner is the one who knocks, because the showrunner is the one who is always there. Viewers need a central voice to appreciate, and that has become the showrunner. This showrunner narrative has grown repetitive, not unlike the way shows are constructed now, too: we need a dark, troubled lead – think Lee Pace’s faux-Don Draper in Halt and Catch Fire – and we need there to be all kinds of moral ambiguity in every character, so everybody cheats on their significant other. These are things that were established ten-plus years ago, and they’re being maintained to keep the illusion of the medium going. Television has a narrative now, and your new show must play into it. The role of the showrunner has a similarly unexciting template. Pizzolatto is just playing his part, because it is a part we have decided he must play. It is how the genre has gone. We get the world we deserve, and we deserve a man who views himself as a television deity.

It is, of course, an idiotic thing for this otherwise intelligent man to believe. It is an image of a man who is all seeing, who understands all and is able to distill it for us in a Vince Vaughn monologue. This is not a person who exists. But Pizzolatto apparently does not see it that way. When he talks, he does so from a position of ultra-consciousness. He says things like, “I have to rebuild myself every morning,” when talking to Vanity Fair. “‘What’s happening? Where am I?’ I’ve got to locate myself in time. I wake up raw and have to put myself together and focus and be like: ‘All right, Pizzolatto, where are you at today? Are you ready to go? Are you ready to do the things you need to do?’”

When Pizzolatto talks about his dedication to maintaining his authourial voice by working alone to maintain the purity of his work, he is again speaking out of turn. These are not things to be said out loud. They are things to be thought. It is not unreasonable to think these things, and it is debatably reasonable to say them in an interview, but culture would not agree with me here. I bet David Simon has thought similar things, but he knows better than to say them to a reporter. We need to tell somebody he’s great; he’s not allowed to vocalize it himself. For somebody who constantly writes about the past unknowingly catching up to our characters, Pizzolatto has been confusingly caught off-guard by the way history has lead to this place. This artist is simultaneously one we created and one we refuse to allow to exist.

You can’t acknowledge how we feel about you, because you might be wrong. That will change everything, because it is everything.

When discussing his importance to hip-hop, Vince Staples is characteristically cutting and truthful in a way that stands in direct contrast to Pizzolatto’s view of himself. “It’s like, what is a rapper?” Staples says, again to Barshad. “Who are you? What do you do for me? You make songs and you disappear in five years. If that. You do nothing.”

Staples seems obsessively focused on the way history has dictated the present. In an interview on NPR’s Microphone Check, he probably says the word ‘history’ close to one hundred times within the show’s eighty-five minutes, and he frequently goes out of his way to discuss how little he cares about the forefathers of hip-hop. He sees the past, because he is frequently asked about it, but he doesn’t care about it. Staples understands that people frame modern rap by everything that came before it, and he wants to break through that. Despite being embraced for its trappings, he feels trapped by the past.

Nic Pizzolatto feels differently. He likes the history of his position, and he desperately wants to hold onto it. He has been much too up front about this, so the second he slipped up, we were ready. You can’t talk about this, because we’ll take it all away when you stop being right.

In the closer of Summertime ’06, Like It Is, Staples talks in between verses about how he is dealing with us looking at him with a preconceived notion of how he is supposed to be. He is talking about his real life, but the feelings apply to his art as well. We know what rappers are, we think, and Staples views it as his job to prove us wrong. The final verse continues on this thought, as a man clamours to be free from what people think about him before hearing what he has to say. He lives for our amusement, and we’re watching him from the safety of behind this glass, so we can never really know what he’s thinking, therefore we should stop trying. In this, too, Staples is right while also being wrong.

In the closer of Summertime ’06, Like It Is, Staples talks in between verses about how he is dealing with us looking at him with a preconceived notion of how he is supposed to be. He is talking about his real life, but the feelings apply to his art as well. We know what rappers are, we think, and Staples views it as his job to prove us wrong. The final verse continues on this thought, as a man clamours to be free from what people think about him before hearing what he has to say. He lives for our amusement, and we’re watching him from the safety of behind this glass, so we can never really know what he’s thinking, therefore we should stop trying. In this, too, Staples is right while also being wrong.

By thinking his music can only be taken one way, from his mouth, Staples makes a mistake many artists make: that the artist’s intent is what most people take from their work. That is incorrect, and it’s an outdated way of thinking. Nobody ever takes your music the exact way you want them to, just like Nic Pizzolatto is probably somewhere right now drinking Johnnie Walker Blue and mumbling, “Wait until the finale, wait until the finale.” People take these things all kinds of ways, in a fashion the artist can never anticipate. That’s both the pain of the artist and the beauty of art. Once you let go of something, you lose control of it forever.

I can’t pretend for a second that my life has been similar to what is described in the vast majority of rap songs. Vince Staples and I probably have nothing in common outside of our negative opinions toward Chris Paul. Despite Staples’ claims that nobody should be really trying to do so, though, I feel like I understand this record without understanding the experience that lead to its creation. I understood the music without putting much thought into it, really; I was just listening to it, and it started making me think about all these things that have nothing to do with Vince Staples. It made me think of aging, it made me think of my relationship to hip-hop, it made me try to decipher whether LCD Soundsystem has had an influence on rap music, and it reminded me that rappers write some really beautiful lines that don’t get nearly enough credit simply because of the way the genre is widely perceived. Nothing is as it should be, and nothing is how you want it. You can tell it like it is, and you can tell it how it could be, but you must always remember that the former will win.

So I identify with a Vince Staples record, just like I identified with all the rap records I listened to as a teenager. (If nothing else, most rappers write about themselves exclusively, and I can absolutely fucking identify with that.) When I went on my ongoing history lesson, I was perusing the adolescence of the genre; Nas’ Illmatic is the beginning of the genre’s adulthood, and I was most involved with that album as I was legally becoming an adult. I spent a lot of high school listening to the Big Daddy Kane, Rakim, and Public Enemy records that would lay the framework for Nas’ summation of the genre. I didn’t grow up with hip-hop, but I belatedly experienced the genre’s growth alongside my own. I had no idea how I identified with these records, but something stuck with me. And now it’s starting to appear to be a part of me that is unlikely to change.

Summertime ’06 is no different. I love this record, because I will never have trouble identifying with somebody who learns a long-held idea about their world is no longer valid. Things change, and we must remain forever fluid.

Tell it how it could be, sure, but grasp the world like it is. It’s the only way.