Alex writes about Aziz Ansari, The Avengers: Age of Ultron, Ex Machina, and the way technology is perceived.

This is a question without an answer, but I will ask it anyway.

In the mid-1990s, the Internet was viewed no differently than rap music was in 1982: a fleeting fad for people that society did not yet deem important. This revolution will not be livestreamed, they said, for reasons not entirely related to the nonexistence of livestreaming. As such, content providers treated the Internet as something that didn’t deserve any respect; if you had a dial-up connection and the wiles to find their website, you could have all of their information for free. As soon as newspapers figured out how to do so, they published all their content online, and my dumb twelve year-old-self could have it for nothing. This transpired into me knowing I could get anything I wanted, all the time, which was a wonderful thing. I tacitly understood a single thing about modernity: information is free (as long as the information in question is not published by the New Yorker).

It is this basic mistake that eventually killed print media: content providers didn’t properly value their content in all its forms, and as such magazines and newspapers rapidly went out of business through the 2000s. They used the allure of a few more un-paying eyes to potentially make them more print money if what they saw online was appetizing, but they did this without realizing they were primarily preaching to those that had already left the newsprint-covered choir. This, among other things, lead to the general devaluation of information. Had pay walls been instituted in 1995, nobody would bat an eye at them now. You would pay for news, because you have always paid for news. It would just be another thing that is a part of life. Death, taxes, paying for shit.

But this isn’t what happened. One entity decided not to properly evaluate what they had in front of them, and they let it into society, snowballing into modernity as others around them adopted it. So the impossible question I ask is this: what would be different about the world today if print media hadn’t demolished itself? How would your day-to-day life be altered?

Technology abounds. This is obvious. Technology dominates our art. This, too, is obvious. In good art, technology is almost never framed as a net positive for society. This is less obvious, but true.

It is admittedly impossible to talk about these things without sounding like a man who wishes he lived in the past. I am Clint Eastwood, telling these tablets to get off my lawn. As such, I assume I have never sounded less cool than I do now. But as 21 Jump Street taught us, 30 is the new 80, and I’m just playing my part. I can assure you that I do not want to live in the past, however – that would be a foolish pursuit. The idea of losing all I have come to accept as a part of my day-to-day existence is much less appealing than adapting to live within the world that I am already currently inside. I am living in a world of digital hedonism, and it is exceedingly comfortable. What concerns me isn’t so much maintaining control over technology as it is the control technology maintains over me.

Aziz Ansari’s latest stand-up special, the aptly titled Live at Madison Square Garden, is fascinating to me, mostly because it’s not particularly funny. It is a lot of things, but it is decidedly not hysterical. Guts will not be busted. What the special sacrifices in hilarity, though, it makes up for with Ansari’s thoughtfulness. For the majority of the special, he spends his time eschewing the bits about celebrities and pop culture that helped him become popular enough to sell out MSG, instead deciding to grace that stage with what is basically an entertaining undergraduate-level lecture on modernity. For the majority of the special, he talks about how modern technology has made life more anxious in a variety of ways, from simply not responding to people that text you to always assuming there are better plans to be had out there, all you have to do is wait for the right call.

Artists we are interested in always have a tricky line to navigate: that between what it is they want to say, and what will keep their positive career trajectory going as it has. Listening to the crowd in Live at MSG, there aren’t a huge number of laughs, even though the number of people hearing Ansari’s jokes has never been larger. The only part in the second half that kills in the traditional sense comes when Ansari reads an audience member’s texts aloud to prove his points about modern romance. I’m sure Ansari is aware of this lack of lols; he is known for his attention to detail, listening back to his own performances to see which jokes work, and why. This, I suspect, is the primary reason he feels obligated to feature a misplaced Ja Rule impression in the show’s opening third. Aziz thought he needed to add in some more traditional jokes, lest people start claiming he has fallen off, that he’s no longer the stand-up wunderkind he was in 2009. But when Ansari talks about the commitment issues that exist within pretty much all modern people, I would laugh if he wasn’t exactly correct. Ansari is playing the long game: by the end of the special, you’re chuckling because he has been right about everything, and eventually you are laughing at the way you’re living your own life.

Ansari is a modern man, and he knows these are problems. He sees that many of the things he loves have the potential to hurt him in the long run – he appreciates the value of texting, but understands the pain that comes when somebody uses the medium’s lack of immediacy to ignore him entirely. He understands the appeal of continuing to go out in hopes that something might happen, but he understands that it probably still ends in pizza he doesn’t really want and hangovers he never used to have. Ansari grasps the ongoing lack of commitment, knowing he too wants to keep his brunch options open until the last possible second.

And this is the sole problem with Live from Madison Square Garden: a lack of commitment to the bit, as Aziz shoehorns some less than stellar jokes in between stellar ideas. Even without the jokes, though, he’s saying interesting, true things, and he’s saying them in entertaining ways. Live from Madison Square Garden is not the funniest comedy special I have ever seen, but I can think of few I have spent more time thinking about. If art is meant to take a look at your world through a slightly different lens and allow you to view your own life more clearly, then this is that. Ansari must know this, because if he is smart enough to write this special, he is smart enough to understand its weight. He just refuses to give in to his better judgment for fear of sounding like the type of person he used to make fun of.

I wholeheartedly understand this hesitation.

Now, there are admittedly many problems with this hypothetical. There tend to be problems any time one tries to change the theoretical past; for proof of this, see any time travel movie ever made. Regardless of print media’s modus operandi, Napster happens. The revolution wasn’t livestreamed, but it was still omnipresent, and I can only assume there would be some thick-skulled Pressplay equivalent created by the infantile web divisions of newspapers. But let’s assume Shawn Fanning doesn’t exist, and neither do his fellow technological revolutionaries. In this world, the capitalists capitalized on the Internet’s abilities first. Things would generally be harder to access, but that difficulty would lead to more variety to those that felt the desire to access it.

I assume this all paints me as an incredibly conservative person. This probably reads like I’m (at least kind of) arguing in favour of big business. I know how it looks, and I know I have to address this, because it’s uncouth for you to spend so much time reading something so uncool. To this point, it certainly seems like I wanted everything to cost money forever, and I want the owners of the businesses that sell those unchanging goods to remain in existence, so I can continue to consume in a world that doesn’t turn.

This isn’t true. I just don’t view this as a winnable battle.

The second Avengers film is an enjoyable one, because it is a film written by Joss Whedon, and the man understands entertainment. Ignoring the film’s various failings, one cannot deny Whedon’s ability to write unequivocal quips about quivers. The surprising element of the film was that it ended up being an extended take on artificial intelligence, the supposed Age of Ultron being more like a Philosophical Argument Between Ultron and Purple Paul’s CGI Cape. Now, this take is clunky for reasons Marvel films’ ideological pontifications often are: they’re so highly honed in editing that large chunks are obviously taken out at some point along the way. There must have been something explaining why Black Widow cared about Bruce Banner so much, and there had to have been more of a reason for Thor to go off to his primordial hot tub in the second act. But, alas, we must take what we can get, and at least parts of this one were interesting.

The argument throughout the film seems to be those fighting for ‘peace in our time:’ Tony Stark and Banner try to build an intelligent suit of armour of sorts around the world, while that suit of armour prefers to think of peace as gaining autonomy, destroying humanity entirely and starting the world again from scratch. (Different strokes, I suppose.) Four overlong battles and a couple Infinity Stones later, and the Vision comes into play, Stark and Banner’s second attempts at artificial intelligence, albeit this time one with the additional humanity that comes with casting Paul Bettany against a man who sounds perpetually dead inside in James Spader. More battles ensue, Elizabeth Olsen switches sides, and Whedon points and laughs at Zack Snyder’s perception of heroism.

The film’s conclusion seems to posit that humans with failings are still better than an army of identically intelligent robots. Artificial intelligence might be cool and quippy and win Emmys for Boston Legal, but sometimes artificial intelligence also turns Sokovia into a floating island of death. The Avengers and their failings were somehow able to defeat their foes by having a collective vision, despite variations on the ideal existing throughout the team. A uniform system of beliefs is not a way to success; totalitarianism among machines can still be defeated by democracy among supermen. The metaphorical bow on this philosophical struggle is added by Vision as he talks to the last of Ultron’s troops: there is grace in humanity’s failings, Vision says, and that these failings are precisely what make us human. They’re what make existence worthwhile. He is naïve, mini-Ultron says, which Vision concedes might be true because of how new he is to this world. And then Vision puts an exclamation point on his beliefs by murdering mini-Ultron. One of humanity’s failings is murder, after all, and perhaps this murder gives Vision his grace.

Whedon has been oddly forthcoming in interviews about the process of making this film: it was incredibly trying, and all the profiles on him leading up to the film’s release seem to paint him as a man on the verge of death. In an interview with Kyle Buchanan, Whedon simultaneously explained his weariness and gratitude for the existence of the Marvel movies. “Is [The Avengers] me? It’s so baldly, nakedly me. To do something that is as personal as this movie is – on that budget, for a studio that needs a summer tentpole – is an extraordinary privilege.” He especially pointed to Ultron as somebody that he poured a lot of his own thoughts into, thoughts that end up being the driving force behind a lot of bad shit in the movie. When Ultron talks, he is speaking to Whedon’s loveable, hopeful gang of supermiscreants, and Whedon suspects Ultron might be right.

The maker of this film about humanity’s failings believes he himself might be naïve. Whedon is happy to be able to make this film, but he views the system that keeps churning them out is no longer one for him. He knows there will be more to stuff into these overstuffed movies, and the few moments of interest will only continue to dwindle with time, for fear of making a film that doesn’t cross all potential quadrants. Ultron is overcome in the film, sure, but Whedon doesn’t seem to believe that will always be the case. Sometimes, we’re fighting when we’ve already lost. It’s a lost cause, and as such Whedon left the battle before the Infinity War. The Russos can take it from here. Whedon is not the finest director in the game, but he’s certainly not the problem. And we’re driving away our finest humans with a quick embrace of an army of similar automatons of movies, despite that being exactly what these movies say is not ideal.

I was not born yesterday, and have no desire to have been. But it seemed like the clouds had a little more variety twenty-four hours ago.

Here’s my never-ending quandary: my job as currently constructed did not exist until 2009. This is when Canon DSLRs became advanced enough to allow cinematographers to shoot gorgeous high-definition video for the cost of a $900 camera body and a $500 lens, which eventually allowed for smaller companies to see that they, too, can produce video to help promote their products online. And the production of these promotions is where my rent money currently comes from.

Now, I love this job. It allows me to make my bones creating slightly more advanced versions of the bullshit Godzilla movies I was making as a kid. It is a job that allows me to spend my afternoons at the cinema and writing in notebooks, the evenings with basketball playoffs and Peter Biskind books. Faux Gojira has been replaced by Ivory Hours, and the lighting and lenses are better, but I’m still fucking around in a warehouse for a weekend making a stop motion video because I don’t have a good enough reason to do otherwise. This is, to put it mildly, an ideal life. And yet I have created this world I love for myself only because of all the things I purport to hate.

I can say that I would give this all up, this career that I love, to work a normal job in a normal office in my hypothetical version of 2015, but that seems like a lie. To say that would be to participate in the same thing that bothers me about the ever-increasing number of apps that are going to finally bring us eternal happiness; for the early adopters, hope is always just around the corner. I’m simply being hopeful about what could have been instead of what could be. This too, shall be fixed. We can solve this problem. The cure to our ills will enter society, and life will be perfect. There will be no worries, no worries at all.

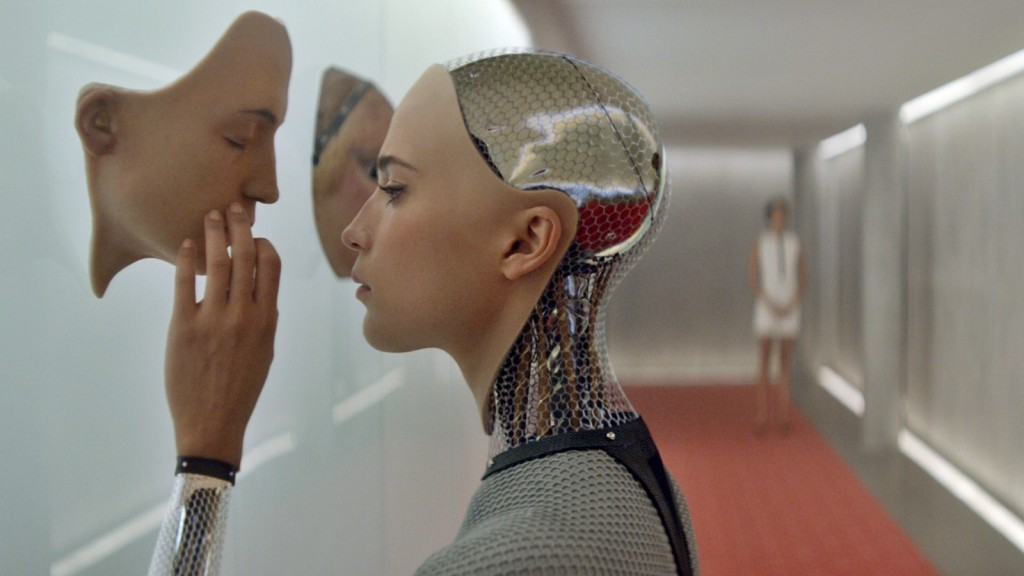

The very wonderful Alex Garland film Ex Machina features a lot of things I appreciate: Oscar Isaac, a solid Ghostbusters reference, thoughtful cinematography, and wordy pontification about the merits of technology. These such pontifications happen mostly between Caleb and Nathan, the former being a programmer of sorts for Bluebook, the latter being the inventor of Bluebook, which is the film’s thinly-veiled version of Google. And Nathan has come up with his finest invention yet: Ava, an artificially intelligent humanoid.

There are many endlessly interesting ideas presented within Ex Machina: the lines between humanity and humanoid, strong interest in sushi and alcoholism among the rich, and the tremendousness of unannounced dance sequences. But what is most interesting is the way Ex Machina shows an intelligent human constantly accepting technology’s quiet power over him. Early in the film, we see Caleb sign a non-disclosure agreement so that he is able to even learn of Ava’s existence. When Caleb reads over the intrusive agreement, he hypothesizes that he needs a lawyer, at which point Nathan says he will merely hold his work back if he doesn’t sign. They can still hang out together for a week, but Caleb will not get to see the new technology we’ll all be talking about a year from now. Obviously, Caleb signs the NDA, because we all sign the NDA, every time. If there’s an opportunity to be ahead of the pack, it must be taken.

This leads to a lot more of that wordy pontification about technology that I (clearly) adore so much. But to simplify things: Ava and Caleb meet, and Caleb digs Ava. Nathan wants to know how Ava makes him feel, so Caleb says ‘great,’ all the while quietly planning a way to get Ava away from Nathan’s more despotic leanings. But, as the third act shows us, Caleb puts his faith on the wrong side. The genius drunk has his problems, sure, but Ava does too.

The idea that Ex Machina leaves us with is that Caleb is an over-trusting dumb dumb. His belief in the purity of technology is erroneous. While Nathan deceives him, Ava’s deception is much more subtle, more thorough and more despicable. She eventually leaves Caleb trapped in a fortress of solitude, likely to die alone and disturbed by the stench of Nathan’s slowly rotting corpse. But what Caleb did was immediately accept the promise of this new technology without thinking about the negative aspects of it. We have learned to distrust humans; we’re still trying to figure out how to be skeptical of technology. It’s still normal to accept new technology as a part of your life, and to never question it, so that’s what Caleb does. He just saw a pretty lady that seemed into him, and said, “Yeah, I can get on board with this.” Ava is playing the impulses Nathan asks about so frequently:

“Do you like it?”

“Yes, but…”

“No but. Just accept it.”

The ending of all of these products – those featuring Aziz, Avengers, and Ava – is not necessarily a sort of unreserved happiness. Vision wins over his devilish doppelganger, but a multitude of franchise-continuing evils lay out there for him and us. Aziz Ansari finds his life partner but ends his closing bit by talking about the inevitability of her death. We can never win, really. As Ex Machina ends, we see Ava on a sidewalk, standing still while unknowing humans walk around her. The film cuts to black as she steps among the crowd, finally joining society for herself. The film ends here because nobody can ever cogently explain what happens next; once a technology enters society, there’s no telling how it will be used, or how it will affect us. We let it out there, and it does the rest. As soon as you let go of something, you lose control of it immediately.

All new technology is designed to increase our power over things that were previously out of our control. Hammers made us nail overlords, perpetually threatening to strike them down into their wooden prison. Iron Man gave us the power to see a gang of our long-beloved comic book heroes grace the screen in a form that was true to canon. But, of course, there’s always an unforeseen effect; hammers double as crude murder weapons, and the safe decentness of Iron Man allowed a whole army of boringly okay movies to exist. Regardless of whether or not you initially use them this way – or if your ticket purchase in 2008 created David Ayer’s Suicide Squad – the opportunity has been taken.

My most prevalent concern about modernity is that, as technology increasingly gives us the feeling that we hold power over everything, in reality that can never be the case. Even the makers of technology can’t control how others will react to them. The most important aspects of life are inherently beyond our control. There will always be something. It is this quiet dissonance that will make a lot of people sad forever.

Technology abounds. This is obvious. Technology dominates our art. This, too, is obvious. In good art, technology is almost never framed as a net positive for society. This is less obvious, but true. And yet we never listen, because we don’t have to.

(I think) I’m happy that this essay exists. Few people read these words but the mere fact that I know one set of eyes does is just enough to keep me making them, and I view these thought experiments as valuable to my day-to-day being. I suspect if I existed as an adult in a pre-Internet world, I wouldn’t write these words, because where would I send them? Nobody writes for the simple pleasure of forming words; they view a journal as a memory aid for the future, or they pen overlong thoughts on pop culture because they see their ideas as worthy enough to spend all that time scrawling them out. In my pre-blog world, I would mail logical thoughts on Ray Allen’s unrewarded NBA Finals MVP performance to far-flung, Internet-less friends, but that is an opportunity that evaporated with age. It was kind of weird then, but it would be especially weird now. I assume my thoughts would remain trapped in my head, undeveloped and ignored. Nobody would hear, so I would keep it down. This might not necessarily have been negative.

I am writing this because I am concerned by what I have lost, without quite realizing what my desire to return to it would involve giving up. No matter where I am, I will be frustrated, because we all are, all the time. I assume there is no point in human history where we were consistently content. We need something to talk about, Gutenberg needed something to print about, I need something to blog about, and bitching about things is so very easy. Whether we’re looking forward or backward, the only constant is that maybe we shouldn’t be looking too hard either way.

This is a question with an answer, but don’t bother asking.