James looks at the change in movie voice acting over the past 20 years, with a focus on Billy West.

As I watched the trailer for Brave, Pixar’s latest release, I thought I recognized the voice of Merida, the film’s main character. The problem of not being able to figure out who the voice belonged to haunted me for approximately the next ninety seconds of the trailer, before I looked up the movie on the Internet Movie Database. It ends up that the voice belongs to Kelly MacDonald, a Scottish actress I knew best as the underappreciated Carla Jean Moss from No Country For Old Men. She was also in Boardwalk Empire, one of those movies with the kid wizard I don’t care about, and Trainspotting. While those are some big credits, and she has been working steadily since 1996, I wouldn’t call her an A-list actress and it surprised me that she is the star of such a big release for a studio as popular as Pixar. It’s not often such a large film opens with a lead actor or actress that the casual moviegoer probably hasn’t heard of*. But this is different. This is animation. Since you don’t see their faces, you just need an actor with the proper voice, right? Well that makes sense to me too, but increasingly isn’t the case anymore. And no one is more painfully aware of this than Billy West.

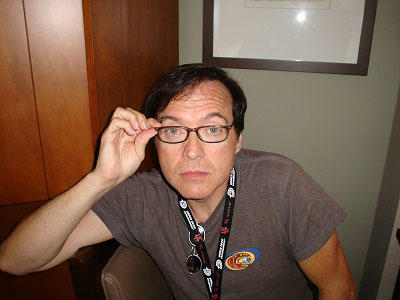

Billy West’s name is known even less than Kelly MacDonald, but I’d be amazed if you hadn’t come across his work before, even if you didn’t know it. He is one of the most prolific voice actors working today, with IMDb crediting him as an actor on 176 different projects dating back to the late 1980s, and many of those see him playing multiple characters. West started to gain national attention for his many crude and hilarious impersonations on The Howard Stern Show, ranging from people like Lucille Ball to Larry Fine of the Three Stooges. From there, he went on to voice dozens of animated characters on Family Guy, Dilbert, King of the Hill, Powerpuff Girls, Johnny Bravo, The Oblongs, Hey Arnold and many more. And it’s not just the amount of work he has done, but the prominence and longevity of many of his roles. He portrayed Doug, among others, on the Nickelodeon show of the same name (until he was replaced when the show went to Disney*), as well as the title characters of Ren & Stimpy. Recently, he is likely most famous for his work on Futurama, where he plays so many major characters that entire scenes are often comprised of West talking to himself in his roles as protagonist Phillip J. Fry, Dr. Zoidberg, Zapp Branigan, Professor Farnsworth, and others.

*And the show jumped the shark. Who thought Patti’s haircut was a good idea?

His wide range of voices has caused many people to call him ‘the new Mel Blanc,’ which is both a massive compliment in voice acting circles and a harsh reminder of how little credit voice actors are given outside of those circles, as many casual animation fans are unsure who that even is. Mel Blanc was the voice of most of the major Warner Bros. cartoon characters in the 1930s and 1940s, including Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Sylvester the Cat, Tweety Bird, Porky Pig, Yosemite Sam and many, many more. He was known as ‘The Man of 1,000 Voices’ and a tally of his career actually shows this nickname is probably a little conservative. It is estimated that when Mel Blanc died, 20 million people heard his voice every day, yet despite this, many don’t know who he is or what he did.

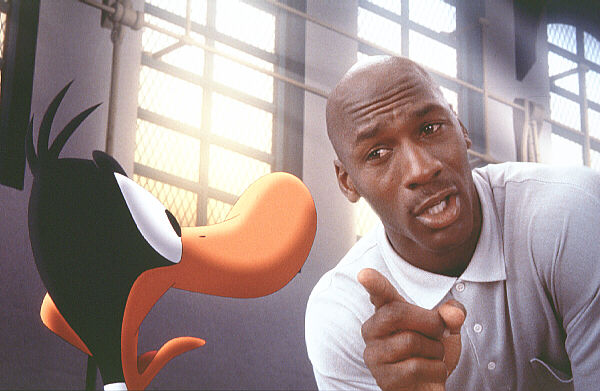

Billy West earned his nickname of ‘the new Mel Blanc’ not just by being extremely prolific and talented like Blanc, but performing some of Blanc’s original trademark characters. In many cartoons, video games and commercials, West has played iconic Blanc characters like Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd. A major milestone for West came when he played these characters in Space Jam, a film my father once described as the loudest, most colourful movie he ever fell asleep to. The entire experience was not as glamourous as West likely hoped. Although playing the character billed above Michael Jordan, one of the most famous people on the planet, West was met with much less than the star treatment. When the premiere of Space Jam took place at the famous Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, West and the other voice actors weren’t invited to either the red carpet or the after party. In fact, the voice actors’ viewing of the premiere was in a smaller theatre next door and, upon questioning this, they were told the big theatre was for “the actors.” West is quick to point out that all the actors in Space Jam couldn’t fill that theatre, and that seats that could have been occupied by he and the other voice actors were filled by people who had nothing to do with the movie, who were there merely to be seen and add star power to the premiere.

“I know this movie is about believing in yourself, but I don’t believe you matter enough to sit in the same room as me.”

In interviews about his experience with Space Jam, West’s feelings of under appreciation and disrespect are quite apparent, but there’s another related subject that can quickly turn him much more upset, and almost militant. That subject is not how live-action actors are treated compared to voice actors, but how they are simply replacing voice actors, and making more money doing so. There has been a change, starting about two decades ago, where major films (and to a lesser degree, TV shows) have been turning their backs on voice actors in exchange for the exponentially more well-known names of live action actors. Here is West answering a question on the versatility of voice actors in an interview with The AV Club:

“We do multiple voices. We used to save producers’ asses, because they’d hire you and say, “Well, we were going to get six people, but we can’t afford it. Can you do this, this, and this?” And you’d do them, and they’d be perfectly happy, and they’d save a bundle of dough. Now, it’s the exact opposite. The minute they mention a CGI film, they’re already looking to see what Renée Zellweger is doing. They’re already looking to see what Billy Crystal is doing. This doesn’t make sense, to do what they do – spend zillions on visuals, and then have this totally fucking flat-lining voice track. You know, “Hey, I’m Will Smith, I’m a clam! I’m Will Smith, I’m a kangaroo!” All you bring to the performance is your own ego. They’re just being themselves. Let’s put it this way: Cameron Diaz is the highest paid voice actress in history: $20 million for Shrek. Why? Because she has a 9-foot mouth? That works somewhere else, but not on tape!”

While it could be easy to write this attitude off as jealousy, he is right that there is a definite difference in their methods and in the results. West’s method at auditions is to come in, look at the drawing of a character, work with the animators, writers and director on the project to get to know what the intended personality is, and then create a voice from scratch. Cameron Diaz in Shrek sounds like Cameron Diaz in everything else, and it is not difficult to see how frustrating this must be to other voice actors. It seems similar to training your whole life to be a marathon runner, and then being replaced by somebody who is allowed to use a car, and also earns an additional $20 million dollars to do so.

This trend of replacing trained voice actors with A-list celebrity actors has a widely-recognized beginning: Disney’s Aladdin, released in 1992. While there are definitely examples of celebrities and established, live action actors’ voices appearing in animation earlier than 1992, that method of thinking was the exception until Robin Williams’ role as Genie helped generate a lot of buzz and, more importantly, dollars. Once Aladdin made over $500 million at the box office, it was basically a wrap for voice actors as leads of big budget animated films. After this, Disney and many other studios creating animated content for the big and little screen scrambled to fill their voice roles with famous faces. Disney’s next animated film, The Lion King, had a cast including Matthew Broderick, James Earl Jones, Jonathan Taylor Thomas, Jeremy Irons, Whoopi Goldberg, Nathan Lane, and this time the film pulled in nearly $1 billion. Pixar joined in as well, when their debut feature length film Toy Story gave us Tim Allen and Tom Hanks sounding like Tim Allen and Tom Hanks. With a few exceptions, this is how the heavy hitters in animation have been doing business since.

[It should be noted that Pixar is often the exception to this rule (not including the Toy Story, Cars, and debatably the Monsters Inc. franchises). The studio tends to rely on less-known-but-still-kinda-known actors like Patton Oswalt (Ratatouille), Holly Hunter and Craig T. Nelson (The Incredibles), Albert Brooks and a pre-daytime talk show Ellen DeGeneres (Finding Nemo), or an Apple computer (Wall-E) to play their leads. While this is far from the old school approach, it is different from the star-studded casts of Dreamworks’ animated films.]

There are two surprising things about Robin William’s contribution to this change. The first is that Billy West is not upset at him at all. Despite the harsh words West has for celebrity voice actors in the wake of the changes that resulted from this performance, West seems to show no ill will at its source. Here he is when asked about that performance in the same interview:

“Williams understands sonic performances. He understands what it’s like to change your voice up. He understands what it’s like to have theatre of the mind—and with your little strip of vocal cords, you’re going to create heavens and hells and universes and populations of people, which is the whole idea that a voice person has in their head.”

West certainly gives Williams’ performance much more credit than Cammy D’s, which is made more interesting when you look at how little credit Williams himself wanted for it. In 1992, his movie Toys was being released only a month after Aladdin, and to keep focus on that film, which Williams felt was a better representation of where he was in his career, he had stipulations in his contract that he nor his character was to be a major part of Aladdin’s advertising campaign. Disney went back on these conditions, causing a massive rift between the 2 parties that went on for years and made Williams refuse the Genie role in the subsequent sequels. Despite this specific desire for a lack of publicity of his part in this film, it is Aladdin that is widely viewed as the influx of live action actors that has West so furious. Studios look for the recognizable name and face, even if all you get is their untrained vocal chords. It seems that these voice actors who trained their whole lives to lose themselves into characters have done such a good job at it that they have lost a lot of jobs and money in the process.