Alex writes about Michael Bolton. Go figure.

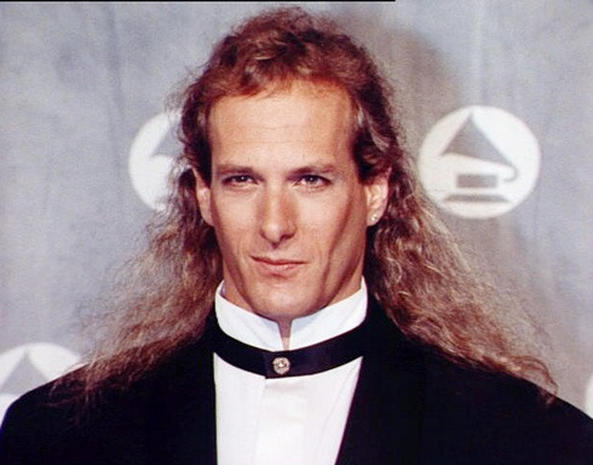

‘What do you see when you look at Michael Bolton?’ the writer asked, accidentally paraphrasing a Michael Bolton song that probably exists.

If you are watching a Bolton music video, what are you looking at? If you’re watching The Lonely Island’s Jack Sparrow, or Bolton’s Lonely Island-produced Big Sexy Valentine’s Day Special, are you laughing? What about when he features on Kid Cudi’s 2013 song “Afterwards (Bring Yo Friends)?” Why? Are you laughing with Lord Boltron? Or at him?

These are all questions I have asked myself more than once, more times than 1000. Michael Bolton, to these hazel eyes, is one of the funniest comedians operating. Even though he would presumably not describe himself as a comedian, everything he does in front of a camera makes me laugh. When he’s dressed as Erin Brockovich in service of The Lonely Island, I laugh. When he’s dressed as Forrest Gump in service of The Lonely Island, I laugh harder. When he’s giving an interview on Today, I laugh. When I watch his own, seemingly serious music videos, I laugh. Every single time Michael Bolton performs an action on camera, it looks like he has never done it before in his life, no matter what that act is. Thinking about whether or not Bolton is actually in on the joke simply adds another scoop to this sundae of hilarity.

Presumably, Bolton’s music videos are not meant to be funny – I have a hard time believing he has been making music videos for 30 years in the hopes an unemployed writer would one day write a piece asking “but what if they’re actually comedy?” That’s some Andy Kaufman shit. There’s no way Bolton is giving interviews and clearly being incredibly honest and also intentionally trying to make me laugh. I believe he understands what the joke of Jack Sparrow is, but only barely, because I can never see any of it registering on his face. I can never really see anything registering on his face – thus the basis of his appeal.

While playing a Two Truths and a Lie-style game on The Talk earlier this year, Michael Bolton told host Sara Gilbert was tasked with convincing Gilbert that his birth name was Michael Bolotin. Her response to the statement?

“You look like you’re lying, but I’m going to say [that’s] true.”

She was right.

There has never been a more perfect summation of looking at Michael Bolton: you believe that he’s giving you everything he has, but it still looks like a lie.

There’s a worry underneath everything I’m writing here, a singular concern: does it sound like I’m trying to make Michael Bolton seem like an idiot? I don’t know for sure, but everything I have written thus far seems to hinge on that idea. This is a piece about somebody (and admittedly, the various members of their “team”) not understanding how they’re seen, and therefore making essentially the same music video over and over despite it being hysterical nonsense every time.

But then there’s another, more obvious point to be made: I could not be further from Michael Bolton’s target audience. I’m at least thirty years too young and always have been. I have never owned a Toyota Previa, and never once recorded an episode of Oprah to VHS. Bolton is simply not making music for me, minus the rare exceptions this decade when he has been asked by Andy Samberg to do so. When Bolton is giving an interview, it’s for the people that like his – as I’m sure he would prefer I call it – real music.

I think everything Michael Bolton does is hilarious. Choke on a hamburger, spit take a Pepsi all over your Apple TV-levels of hilarious. But is Bolton funny because he’s ignorant, or is he funny because I am?

There’s a difference between looking silly and looking like you have never been on camera before, despite mounds of documented evidence proving that you have been. To wit, Jeremy Renner is making music now. It’s hilarious. He has a single called Heaven Don’t Have a Name, a video called Main Attraction, and another track named Nomad. All of these songs are terrible, and it’s funny that they exist. It’s funny that a person who has been nominated for an Oscar for acting feels compelled to make – to use the comparison everybody else has – Imagine Dragons songs that sound shittier than actual Imagine Dragons songs. When we send around links to Jeremy Renner’s video, we are implicitly saying “this guy has everything, so why does he do this?” Why does he still feel compelled to open himself up to this level of embarrassment? I don’t know, none of us know, but we all love watching this type of stuff happen. (If Leonardo DiCaprio followed up Once Upon a Time in Hollywood by starting a Taking Back Sunday cover band, it would be the only thing the pop culture corner of the internet talked about for the rest of the year.)

Jeremy Renner and Michael Bolton both make dumb music, and they make dumb music videos to go with them. But there’s a difference. Renner is doing this because he wants something he can’t have, or at least wants people to view him as a diversified human, a so-called multihyphenate. Bolton is doing this because this is who he is all the time.

When I watch Renner’s Main Attraction video, it’s fine. Renner understands how to be on camera. The whole thing is most certainly stupid, and it looks incongruent watching Hawkeye perform with a band, but he can sell all that shit of him walking in the desert and touching blue light rods or whatever. Anybody would look stupid doing that, but Renner manages to look slightly less so. Renner looks like a human being reaching only slightly out of the confines he has the ability to occupy, whereas if Michael Bolton had made this exact music video I would still be laughing too hard to write a paragraph about it.

If you look at an old Bolton video – Said I Loved You… But I Lied, for example –he’s doing different versions of the same things Renner does. He’s in a desert, reaching out to nature, standing on a cliff face, wearing a shirt with a comical lack of done up buttons. Every shot looks like a manufacturer’s default for a computer desktop background.

Or perhaps it’s one of the videos featuring a little acting, where he romances Teri Hatcher at her father’s gas station before engaging in some truly repulsive kissing. Intercut with this are images of Bolton, alone in a room with shafts of light peeking through the thickest smoke machine clouds you’ve seen outside of Blade Runner. And he’s singing, looking so deeply uncomfortable doing so. Bolton in these music videos is a megastar, performing a song to his fans for maybe the millionth time. Yet he looks like this. And this awkwardness has never truly gone away. This is who he is.

Michael Bolton never looks like he belongs, even when in the arena that is his only real occupation. He has performed When a Man Loves a Woman for a paying audience more times than you have brushed your teeth, yet he seemingly has not found a way to look comfortable performing it. And, as you can figure out, I am obsessed with this.

In my world, obsession brings Googling. Searching for Michael Bolton interviews, however, results in not a lot of options from the distant past. Most of what I can find is within the last six years, and most of that is essentially the same. Bolton did a significant morning show tour earlier this year, because he plays music for people who still watch morning shows. He was promoting his “50th anniversary of working in showbiz,” which is hilarious on its own, but whatever, people in their 60s tend to think weird shit is a good idea. (At least one of your parents will probably announce an intention to try “snowshoe golfing” by the end of this winter.)

The point is this: Michael Bolton was so famous that a plethora of interviews with him from the 1980s and 1990s must exist. Mary Hart interviewed him on Entertainment Tonight at least once, I’m sure. If I was a proper scholar with a NexisLexis password (or a proper writer with a willingness to travel to a library), I’m sure I could uncover a handful of Billboard pieces about Bolton, perhaps a “let’s investigate this bizarre phenomenon” sort of Rolling Stone piece, and a bunch of selections from printed publications that have since gone extinct. Bolton was too famous for people to not interview him. He has sold 75 million records, which must have been interesting to at least one journalistic contemporary. But he wasn’t famous to the right people, the people who would bring Bolton into the future with them.

When I research one of these essays, a more-personal-than-scholarly-but-still-a-little-scholarly sort of thing, I do what most would do. I look at the subject’s Wikipedia citations. It’s the quickest place to find a diverse group of sources over a diverse time period, with infinitely more variance than a Google search would provide. From there, I follow all the leads I can find in these pieces, and use the most interesting phrases to accentuate secondary Google searches, to help me properly dive deep.

This strategy works as a jumping off point, almost without fail. In order for this strategy to work, you need the type of person who cares about Wikipedia, or who cares about the subject, to add these citations to the subject’s article. And perhaps unsurprisingly given his presumed audience, nobody seems to have done that for Bolton. The people who love Michael Bolton love him for his music, perhaps love to see him live, and that’s about it. I just wrote about Don Cherry – who theoretically plays to an audience not excited about extending with his Wikipedia entry – and yet this strategy worked just like it always does. I found plenty of diverse material on Grapes, relatively easily. Almost every sort of even minor celebrity has somebody willing to make sure their life is actively archived in a general, Wikipedia sort of sense but, as always, Bolton remains an indecipherable exception.

That’s what makes this 50th anniversary tour as interesting as it is: for once, it seems a celebrity gets to truly write their own history. Bolton controls the narrative, because nobody else ever cared to try. He is the type of performer he is, and that can never change because we actually remember him, but beyond that, it’s all up for grabs. If Bolton wants to exclusively talk about his work as a philanthropist, he can, and it will actively become difficult to find anything else about him without digging deep. (Like, for example, some scandalous investing done by his foundation in the 1990s.)

When you know one thing, expect one thing, and get one thing for long enough, the person giving it to you will be so deeply uncool that he will one day get to control everything.

One thing that Wikipedia citations has been helpful for, however, is Lonely Island-related research. It turns out Akiva, Andy, and Jorma have at least a couple of people who want to remember their history. Michael Bolton, for one: he loves telling the story of their inaugural collaboration on talk shows, it seems.

In the summer of 2010, the Lonely Island were writing the song that would end up being Jack Sparrow, and were trying to find a guest that fit what they were looking for, collectively deciding Bolton was the perfect option upon his name being mentioned by Akiva Schaffer. They then pursued Bolton until he agreed to perform on the track, after a series of rewrites to tone down language Bolton felt his fans wouldn’t support. On May 7, 2011 the music video was released as a Digital Short on Saturday Night Live, and everybody laughed. The song was funny enough as written, with Bolton’s true commitment to the bit sending it over the top.

The core of Bolton being funny in the Jack Sparrow video lies within one fact: we all knew who Michael Bolton was somehow, but he had also been absent enough from our lives to never have to think about him. That way, when he pops up, it’s odd, and then it only gets odder to watch him sing lyrics that are so incongruent with how we understand his place. Bolton is a forgotten but not forgotten man, because he was once so famous that some people will never forget him.

Hard left turn upcoming: this is going to, briefly, be about Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. In this recently-released film, superstar auteur Quentin Tarantino re-imagines the Manson Family killings in a way that seems meant to imply that all that was good in 1969 could have remained happy and placid, had a different door been kicked down and cans of dog food and flame throwers been implemented. Sure.

The lingering question to my eyes, the question posed by the final prolonged high angle crane shot of Sharon Tate’s home, is: would somebody else have followed Rick Dalton into that house at some point? Would similar murders or something replacing them have happened, thus ending the Summer of Love anyway? I mean, probably. Nixon was already President at this point, after all. Everything ends, which is why we need Tarantino movies to provide us with an escape from reality.

The thread running through the new film is a lesser version of the question of fate running throughout Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, but with Once Upon a Time it brings up more personal questions about the film’s creator. Does Tarantino fear change? To an extent, surely. That doesn’t seem that odd. Does he fear change in a way that stunts his human growth? Potentially, but I’m not here to tell somebody how one should live their life. Tarantino has always been obsessed with the media products on display in this film, and he remains so. Some people don’t really change all that much as time passes, or do so incrementally enough that we don’t really notice as it happens.

I can’t say I loved Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, despite my excitement for its release and the fact that I will probably see it five or six times before it leaves theatres. Something about the movie simply felt a little lifeless; it had all the self-indulgences of a Tarantino picture, but it never really came together. The idea was that we see all these feet and all these cars traveling in different directions, yet ending up in the same place for the climax, but the journey didn’t feel propulsive enough to make it work, the stops along the way not funny enough to make us enjoy the pauses. It felt like everything I loved about the movie had been done before, done better in other Tarantino movies, save the new wrinkle of some incredible driving shots and gorgeous 1969 production design.

That said, when we got to the final, lingering overhead shot, I liked the choices. I liked the very ending of the movie because the tension remained after the police and ambulance left Dalton’s residence, as he went to get a drink with Sharon Tate. It felt like somebody might walk in the door right behind them and fuck the whole thing up anyway. In its placidity, the ending remained at least potentially turbulent.

This film, and Quentin Tarantino’s career, does not fit the Michael Bolton Wikipedia problem. QT’s life is documented. He is the opposite of Bolton – Tarantino is not only popular, he’s also critically beloved. He has plenty of detractors, but most of the time even they will give it up for his technical aplomb. I assume even Spike Lee respects those crane shots. Not to mention, Tarantino is also really good at talking. He has self-mythologized as we have gone through his career with him, writing the Wiki as he speaks, with nerds like me jotting it all down to enter later.

Watching Once Upon a Time in Hollywood feels like watching something disappear as it’s happening, both in the reality of the movie and the reality of movies. It is exceedingly rare to see a $95 million film about adults simply existing, featuring two of the biggest movie stars in the world. In fact, I doubt it ever happens again. Once Upon a Time truly feels like the last of its kind, a sort of one-off where Sony was willing to overpay in a bidding war to be able to tell people “we produced the new Tarantino film.” The sun is setting for maybe the last time, so I feel compelled to watch the gorgeousness fall off in the distance.

The movie proposes the idea “what if it didn’t have to end?”, and when it comes to releasing major films like this, despite my negative comments about this specific film, I truly wish it didn’t have to end. (It is possible to not love a film and still wish more films like it existed. This is not an incongruent thought.) But I worry it might already be over, and I’m holding on a little too tightly, futilely wishing it wasn’t.

When you watch a Bolton performance from the 1980s and a recent Bolton performance, they look the same. Truly the same, minus the hair. The music video from his 1987 breakthrough Sitting on the Dock of the Bay and his 1995 single Can I Touch You… There? are essentially the same. Post-1990s, Michael Bolton has spent the majority of his time in a recording studio covering pre-existing songs. Songs of classic cinema, the songs of Sinatra, a Motown tribute, and re-arranging his own hit songs with an orchestra is how he now spends his time. Bolton hasn’t released an album with original songs on it since 2009’s One World, One Love, presumably because he doesn’t feel he needs to, because there’s no financial reason and (apparently) no artistic reason. Bolton broke through with an Otis Redding cover, and his biggest hit is a Percy Sledge cover, so by his logic nobody cares if he just keeps performing the same songs he and his fans have already agreed to love. “I might as well cover my own pre-existing music with an orchestra,” he thinks, and it seems Bolton is able to believe this isn’t a problematic impulse.

This is who he is, and no matter how bizarre it appears, it still works for him. Bolton is a person who continues to exist, and continues to remain unflinching. This is what he does, and so he shall do it.

Do I envy him? No. Nothing about his life seems particularly appealing. Well, almost nothing.