Alex writes about the career of Ryan Gosling, and a particular ringing left in his ears by First Man.

There’s a pervasive feeling that washes upon a viewer at the conclusion of First Man, and if one were to listen to the man to the left of me that feeling is apparently “…what?” If you were to ask the man to the right of me, he wouldn’t give you an answer, because he left during the moon landing sequence for some reason. First Man does not immediately draw attention to the things that make it special; it often looks and feels like Interstellar if Interstellar had been shot by the crew of Friday Night Lights. First Man is a relatively simple biopic, a movie about an infamous man with an infamous goal who accomplishes it in an infamous way while saying an infamous sentence. It cannot possibly be new, and it isn’t.

Throughout the film, I remember thinking to myself: “Do I like this movie? Am I bored?” I couldn’t really sort out how I felt about the film as it was going – the set pieces felt like less expensive versions of sequences I lost my shit over four years ago in Christopher Nolan’s aforementioned space odyssey. Conversing with a cinematographer friend later, he had felt the same way watching First Man. We commiserated on things we thought we might hate, or things we might love, but were primarily unsure about.

As hours and days passed, I found the pervasive score of First Man bouncing around my head. I was humming the repeated themes while making coffee, drinking coffee, and accidentally spilling coffee on this keyboard in front of me. I spent a weekend in a small town attending a wedding, assuming some dance floor fodder like Shake it Off would be replacing the sounds of Neil Armstrong’s quest. Even a briefly popular and absurdly catch Kendrick Lamar/A-ha mash-up couldn’t rescue me. As such, I was stuck bouncing around my musical memories until I could see the film again. And the images bounded with the pulsing music always lead me back to thinking about the film’s star.

I have a strangely clear memory of seeing Half Nelson for the first time in early 2007, the sort of memory one has upon experiencing something that grabs their attention in a new way. Half Nelson’s handheld cinematography was engaging without being overbearing, and the semi-improvisational style of filming its characters made every performance feel more naturalistic. (This also happened to be the perfect time of my life to see a movie with a climax scored by Shampoo Suicide, a choice that certainly had an effect on my viewing experience.) Of course, none of these specific thoughts are running through my head on the walk home; at this point in my life I’m mostly walking home in a dazed, semi-numb feeling, numbness unrelated to the snow seeping in between the seams of my Nikes. And all of these thoughts came back to one simple core element of the film, a thought about the man at the heart of Half Nelson.

‘I guess I’m a Ryan Gosling fan now,’ I thought.

Up until Half Nelson’s release, Ryan Gosling wasn’t exactly somebody I thought about. To most people like myself he was simply the guy from The Notebook. Given the fact that I am Canadian, however, I knew more about him than the average person (because the instant a Canadian becomes semi-famous in America they immediately become an unfathomable megastar in Canada*). Add in that Gosling was born in my hometown and you have a magic elixir of accidentally reading countless local newspaper stories about the town’s golden boy made good.

*The notable exceptions being all members of Nickelback, who remain our greatest villains not named Ford or Bernardo.

Gosling was famously a middling Mouseketeer next to the Britney/Christina/Justin triumvirate, living in Florida as a 13 year old and spending much of his free time at Disney World. As time progressed he became Young Hercules and the scrawny kid from Breaker High before branching out into film and, in 2004, putting on a newsboy cap and becoming the aforementioned guy from The Notebook. There were other efforts: starring as a Jewish Neo-Nazi in The Believer brought Gosling his first dash of critical acclaim despite being a widely unseen film. There was that Sandra Bullock serial killer movie about trigonometry, too, but Half Nelson was the first time Gosling came into the spotlight for being a potentially great actor.

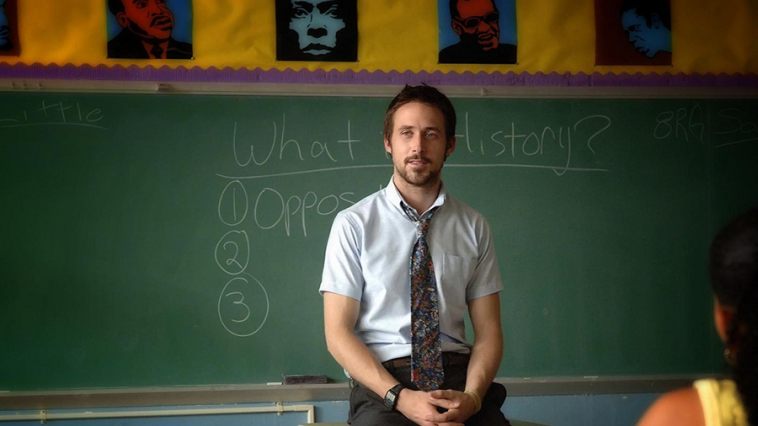

Half Nelson is a not-quite-great but totally-very-good film about a drug addicted teacher developing a friendship with one of his students. The basic idea is relatively rote, mid-2000s type indie stuff, but the execution is solid: director Ryan Fleck and partner Anna Boden remain some of my favourite filmmakers to this day. In Half Nelson, Shareeka Epps is spectacular as Drey, and Fleck & Boden craft all of this into an engaging film about the necessity of fixing ground-level issues before approaching systemic ones. But at the core of the film, the core that was surely necessary to get it produced, is a lively, thoughtful performance from Ryan Gosling as teacher Dan Dunne.

Even up to this point, Gosling’s career had been unpredictable to an extent – after the fervent success of The Notebook, it is presumed that Gosling could have had any number of leading man type Hollywood roles, and yet he chose not to accept them. Profiles of Gosling from this time mention how little he cared about making a movie for the sake of making a movie and only cared about doing the right thing, borrowing a car and money from his agents to keep his life going while accepting scale for lower budget movies like Half Nelson.

“I read a lot of scripts. In my opinion, most of them aren’t good or aren’t about people,” Gosling said to W Magazine writer Marshall Heyman in 2006, during the lead up to Half Nelson’s release. “So I keep waiting, and I read and read until I find something that was written by a person about a person. It’s not like I have some real fancy requirement. That’s it.”

On the second viewing of First Man, it did not take long to figure out why this film had stuck with me, and specifically why composer Justin Hurwitz’s music had. By the eight-minute mark I could have walked out of the cinema entirely satisfied that my question had been answered.

First Man begins with a much-praised sequence of Neil Armstrong in an X-15. An engaging and solid sequence, sure, but not important for our purposes here. Then we see Neil and his wife Janet with their daughter Karen, as Karen is dealing with a brain tumour that the film leads us to believe shall not be defeated. Neil is doing everything he can to help, staying up late in his office and making calls while scrawling in notebooks that never get cleared from his desk, all of which is done alone, all of which is done in vain. Karen dies, with the sound of her casket being lowered into the ground prominently featured amongst the sound of tears and rain. Neil leaves the wake, retreats to his office, cries, and clears all of those previously necessary notebooks away. Neil has nothing to focus on now, nothing on his desk but tears caused by what he might view as his own failure. A seemingly innocuous move, he puts Karen’s bracelet away inside his desk drawer.

The next morning (the film doesn’t make the timing 100% clear, but it is at the very least soon after the funeral), Neil wakes up, says to Janet he thought he might go to work, and after a brief pause that is among Claire Foy’s best work in the film, Janet says “Okay.” The film cuts to a wide shot of the bedroom, where we see a bed that has no sheets on it, and then we cut to Neil plucking away at his desk at work. This is where the film’s most pervasive theme, the theme I had been humming for a week and a half, the theme I had been waiting to hear again, starts.

In that moment, I understood the film. It took me longer than most viewers, I admit, but eventually director Damien Chazelle’s efforts worked on me. As soon as one task had been deemed over for Neil, the next had to begin, and there was a new theme to accompany it, a new problem to be repeatedly mulled over. Neil has begun staring above him, looking at a moon that seems far enough away that he must get there. The moon becomes the place to get to for Neil, the place furthest from Neil’s own tragedy, and the hope of getting there is the one thing that can eclipse the sadness he feels on Earth. And all of these thoughts hit me in the span ten seconds, and all of them made me feel incredibly shitty.

In short, First Man is a deeply sad, unfathomably lonely movie.

Post-Half Nelson, Gosling’s career takes an intriguing turn, in that he kind of goes away for a while. There are films that he would have had in the can pre-Oscar nomination like 2007’s Fracture, a film featuring Gosling sparring with Anthony Hopkins’ murderous maestro, a film that remains deeply entertaining if a purely Hollywood genre piece. There was also Lars and the Real Girl – a solid film about community-based empathy and also Ryan Gosling being in love with a Real Doll – but after that Gosling doesn’t have another film released for years. Not that there weren’t any attempts.

Peter Jackson’s terrible 2009 film The Lovely Bones stars Mark Wahlberg, but it was initially supposed to star Ryan Gosling. Gosling, cast in the role while twenty-six years old, would later admit to feeling odd that the filmmakers wanted him for the role of a father of a fourteen year old, given Gosling’s age. Jackson’s idea was to thin out Gosling’s hair and age him with makeup, a stupid idea that fits right in line with this very awful movie. Gosling’s idea, unbeknownst to Jackson, was to grow a beard and chug melted Haagen Dazs until he was 60 pounds overweight. It seems Jackson did not appreciate this, and the parties agreed to move forward without one another, and Mark Wahlberg swooped in to give a terrible performance (albeit a terrible performance with Jackson’s desired body fat index).

Talking about it with The Guardian while promoting Lars and the Real Girl, Gosling implied he felt it was a mistake to take the role initially, saying, “The problem is, when you’re just starting out, you’re trying to convince everybody that you can do anything, because you need a job. You train yourself to think that way. And then when you get to a point where you don’t have to hustle for jobs any more, you have to sort of reprogram yourself and think, ‘Well, what can’t I do?’ Because the truth is that they’ll catch you. They’ll put you in anything.”

Asked if it changed his approach to looking at roles, he says, “Yeah, I think so. It was nice to be believed in that much, but it was also an important realisation (sic) for me: not to let your ego get involved. It’s OK to be too young for a role.”

And then he went away. Gosling spent a year learning how to play instruments for his band Dead Man’s Bones, for an eventual album that is surprisingly good – more early period Timber Timbre than Dogstar or 30 Odd Foot of Grunts. He bought a Moroccan restaurant, and he laid the plumbing himself because his attraction to movies that pay scale left him without the money needed to hire somebody. Even before this, Gosling had worked making sandwiches at a local deli following the release of The Notebook.

“That break did me good,” he adds in discussing his hiatus, “in the sense that taking some time out meant I had some experience of life. Experience of normal life, I mean, that you can then reflect in a movie. It’s not good just to have life experience of film-making and that’s all. It’s hard to play a real person when you’ve been in jets and town cars for three years.”

Eternally curious, a pervasive fact about Gosling seems to be his desire to learn new skills. He learned how to rebuild the car he pilots in Drive from a mechanic named Pedro, and one of the appeals to La La Land for Gosling was having a few months to learn jazz piano and polish some of his long-dormant Mouseketeer dance skills. When it came time to shoot Blue Valentine, I fully assume he actually worked as a mover and housepainter for a month or two before shooting as research for his role as Dean, despite having absolutely no confirmation of this fact.

Upon his return to acting in 2010, Gosling was featured in Blue Valentine, a beautifully heart-breaking picture that features some of his best work*. Writer/director Derek Cianfrance was able to tap into the same talents in Gosling that made him shine in Half Nelson, playing both to his improvisational naturalism and his apparent desire to drink melted ice cream**. Semi-famously, production halted for a month between the Super 16mm-captured courtship and the cold digital RED rendering of the dissolution of the marriage, set six years later. During that time, Gosling and Williams lived together in a Pennsylvania house with their on-camera daughter Faith Wladyka; Williams would go home to her family at night, and given child labour laws one can assume Wladyka would as well, but knowing the Gos he probably stayed at the house drinking himself to sleep every night in an effort to perpetually stay in character. When the man works, the man works hard.

*Even though he somehow only gives the second best performance in the movie, topped by co-star Michelle Williams.

**Coincidentally, Half Nelson and Blue Valentine share a cinematographer, Andrij Parekh.

What remains so fascinating about Blue Valentine today is the way it inverts Gosling’s star image from The Notebook, the image that in 2010 was likely still the lasting one viewers held of him. The scenes from Blue Valentine that take place in the past might as well feature Gosling climbing a Ferris wheel to talk to Williams; Dean isn’t that far removed from a modern day equivalent of Noah. But the scenes from the present show how that kind of impulsive dedication can go awry, how the charming love story can so easily go to shit in a six-year span. Blue Valentine never hits this note too hard, allowing it to underline more than take over the scenes, but Gosling’s pre-existing track record as a romantic leading man certainly never hurt Blue Valentine.

Blue Valentine’s release kicked off a long list of Gosling performances in a small period of time: within a year All Good Things, Drive, Crazy Stupid Love and The Ides of March were all in theatres. Gosling seemed to be making a move, cashing in simultaneously on both his acting cred and stardom to play a variety of types of characters. The people who wanted him in their movie post-Half Nelson were finally getting the chance. Crazy Stupid Love co-director John Requa put it thusly to The Telegraph in 2011, theorizing that, “[Gosling] did not want flash-in-the-pan success. He wanted to do it in his own time. Someone really prominent in Hollywood came up to us and said, ‘Good work, guys, you’ve finally made Ryan a star.’ And we said, ‘No, no. Ryan decided to be a star and we were lucky enough to get him. He’s his own man. He came to us. We just said action and cut.’”

It is during this period where the two distinct versions of Gosling become clear: there was the naturalistic, restrained Gosling present in films like Half Nelson, Blue Valentine and The Ides of March, as well as the full-blown movie star Gosling charm offensive contained in movies like The Notebook, Crazy Stupid Love, and eventually La La Land. Gosling had so many strengths that they couldn’t always comfortably exist, so he performed in enough movies to give ample sides of him room to breathe. He’ll play quiet introverts, he’ll learn how to strip a car and rebuild that car and drive the fuck out of that car, and (eventually) he’ll be one half of a charming duo that takes a borderline independent musical to nearly half a billion dollars at the box office.

“It used to be mandatory to sing, dance, and act—to do comedy as well as drama,” Gosling told New York Magazine in 2010. “You came out here and trained. Over time, [actors] got compartmentalized. If you tried to play a character that was south side of a character you were made famous for, you were kicked to the curb, or shamed into getting back in line. The idea,” Gosling tells Logan Hill, “is to go back to the way things used to be.”

This section surely reads as though I am claiming Ryan Gosling is the second coming of Al Pacino or something, which is certainly not the intention, despite potentially parsing that idea walking through the snow in 2007 after having seen Half Nelson for the first time. Like all great actors, Gosling has his array of tricks, and he goes to the same various wells so frequently that he can become predictable. Even watching the more improvisational movies like Half Nelson or Blue Valentine, you see some of the same tendencies popping up again and again, specifically his tendency to portray anger with slightly too much physical movement and his portrayal of sadness with a quick turn of the head followed by an unblinking stare into the distance.

Because of this, admittedly my passion for Gosling’s work faded over the years, notably in this 2010-2012 period as it became easier to see the overlap in his performances. What was once new shall always become old. I saw the same moves over and over, and I still self-identified as a Gosling fan, but I was no longer watching movies exclusively because he was in them. Over the past two weeks though, watching every notable film he has been in this decade (and a large percentage from the decade previous), I have realized those feelings were unwarranted. Initially I just wanted to watch Fracture because it was Sunday, and I was kind of hungover and I had a pizza to eat. On Tuesday I realized I should probably watch The Ides of March again in the name of research, which was impulsively followed by Crazy Stupid Love. Then it was a Thursday when I finished work early and decided to watch Blue Valentine again, a decision that eventually devolved into somehow watching five Gosling movies in a single evening. Something about the man’s career was hard to let go of, even with the repeated tricks being even more obvious when seen in rapid succession.

There is a significant difference between being predictable and being stale, though. Gosling can be predictable, but he is never stale. There is a liveliness to everything he does onscreen, even when he is doing that “stare off to the distance looking like you’re on the verge of tears” thing for the fourteenth time in any given film. And in a time when it’s so easy to do what people are telling you to do in an effort to avoid offending anybody, the choices Gosling makes with his roles are consistently great. Looking at his past six films results in finding an uncommonly fantastic run for a movie star:

- The Big Short – Gosling gets to go incredibly broad for the first time, and it is a joy to watch.

- The Nice Guys – Goddamn is this movie funny and goddamn is Ryan Gosling good in it.

- La La Land – This movie is not fun to talk about with anybody for a number of reasons I have already discussed elsewhere. But Gosling was nobody’s problem with this film, and if one were to ask me to point to the best proper movie star performance of the decade, Gosling as Sebastian is in the conversation.

- Song to Song – This one’s a bit of a cheat, since it was filmed in 2012 and director Terrence Malick’s reluctance to finish a film lead to its 2017 release, but this is Malick’s second best film and Gosling works fantastically within the framework of a Malick film.

- Blade Runner 2049 – Gosling’s one blockbuster foray happened to be a fantastic, famously slow-paced film about Gosling’s character discovering that he is not a Christ figure.

- First Man – (see above and/or below)

Gosling never does what a modern movie star is supposed to do, and even when he does, he does so with an inversion: he’ll make a blockbuster, but he’ll die in it to avoid becoming sequel fodder. He’ll be in a detective movie with Russell Crowe, but Gosling will play his character like he’s Laurel and/or Hardy. Even when he stars in something that reads as obvious – a biopic about Neil Armstrong, say – the eventual picture is not what you had in your mind when the movie was announced. (Nobody expected First Man to be shot like it was Gimme Shelter.) Whether it’s his doing or simply by picking the right people to work with, you never know what you’re getting with Gosling, but more often than not you’re getting something unique. No post-Armstrong role has been announced, but whatever it is will be worth watching*.

*Not so bold prediction: I would bet it is a couple years before we see Gosling play a lead role again, or perhaps any role whatsoever. If he is nominated for an Oscar for First Man, I would imagine that the awards show is the last place we see him for a while, lest one were to stumble into the right deli and found Gosling making paninis.

Gosling’s performance as Neil Armstrong focuses more on the quiet, interior version of Gosling, as director Damien Chazelle creates a world that allowed for the Blue Valentine version of Gosling to appear frequently. The scenes with the Armstrongs at home have a level of naturalism that can only be improvised, and in Neil’s scenes of quiet isolation Gosling suggests an interior monologue that never quite gets vocalized. Occasionally, in scenes of Neil joking with friends or telling Buzz Aldrin to effectively shut the fuck up, the louder, more performative Gosling briefly takes the reins, but more often than not, the subjective cinematic style of First Man required a resolute quiet from its leading man.

After the realization about Armstrong’s attempts to move on from his daughter’s passing, you have a hard time seeing the biopic, and begin to see a movie about a truly depressed human being who refuses to talk to anybody about what he is going through. (It is worth noting that at one point Janet mentions that Neil has never talked to her about Karen, which on its own is a deeply sad admission.) Neil begins to ignore his family more and more as he prepares to leave home, to the point where Janet makes him sit down with his own kids to tell them where he’s going, in a scene clearly meant to mirror the press conference Neil had just been the star of.

In a film filled with tremendous music, the best cue is unquestionably titled The Landing, a cue that is tied to the most exciting moment of the film. In this five minute sequence, composer Justin Hurwitz combines the pervasive theme we have been hearing throughout the film with all sorts of disparate sounds we haven’t heard to this point – we are going where no man has gone before, and Hurwitz brings in pieces of the orchestra we haven’t heard to this point as the scene progresses. In what is the saddest moment in a perpetually sad movie, the music gets bigger than it does anywhere else as we see a reveal of the moon’s surface: the orchestra is louder than it has been, there are more instruments than there will be again, all for the reveal of the lunar surface. And yet, in the wide shot used for this moment, Chazelle decides to keep the frame incredibly empty. You see the moon’s surface, a relative speck of the craft Armstrong is in, and nothing else. The musical choice is classical – this is the first time this has been done in human history so this is a big reveal, and the music is appropriately grand – and yet the visual choice is the exact inverse of how most movies would choose to navigate this moment. This is not triumphant, this is a man using all of his brain muscle to get to what is essentially an empty expanse, but an empty expanse Neil was able to convince himself would solve his problems.

Once on the moon’s surface, we see Neil looking around at only his shadow; he looks up and sees the earth that is now the same distance the moon once was from his home. Quietly, we are meant to believe Neil understands this was a fool’s errand.

Again, First Man is a deeply sad, unfathomably lonely movie.

If there is an unspoken appeal about Gosling, it’s not necessarily his acting choices or his role selection or the fact that he’s remarkably attractive. When people scream for a celebrity, it’s never one of those first two things, and it’s (almost never exclusively) about the third. There’s a certain unknowable factor to Gosling that shines through, and makes what he does choose to give us – those moments of charm in his roles or promotional interviews – all the more appealing. Gosling seems like a regular person who understands that talking a lot about himself is rarely the most interesting course of action. And onscreen he can be so restrained that getting anything out of him feels like a win. Gosling seems like a quasi-introverted person who simply happens to have to talk to these people with microphones and notepads about himself for some reason.

In the case of a celebrity like Gosling who is giving these interviews as part of a promotional cycle, the obvious reason for said talking is “money.” But you can totally stonewall these people while still promoting your film*, and Gosling never seems to do that. Reading profile after profile about Gosling, one fact becomes clear that doesn’t seem to come through in the public’s perception of Ryan Gosling: he’s kind of fucking weird. He seems to like magic a lot, went to Disneyland by himself semi-frequently as a thirty year old, pours way too much sugar into his coffee, and as previously mentioned decided to lay the plumbing in his own restaurant. Are any of these facts troubling in any way? With the exception of the Disneyland one, no. They’re uncommon acts taken upon by a man who lives an uncommon life, and few professions are more uncommon than movie star.

*See this recent New York Times profile on Bradley Cooper, written by Taffy Brodesser-Akner.

The core question of any one of these endless essays I have written about famous people I will never meet is always the same: why do I care about this person? I have spent a lot of time performing research that could only be described as “ever so slightly more than totally fucking meaningless.” I have no real desire to know Gosling, nor do I believe I can do so by engaging in this practice I am currently finishing up. For some reason, there just happens to be something leading me in this direction.

So frequently, Gosling’s finest strength in a role is an act of introversion: he holds everything inside until it’s time to actually vocalize (or the physical equivalent of vocalizing) what he needs to convey. The great strength of First Man, the element I couldn’t grab a hold of on one viewing, is just that. Neil cries alone after Karen’s funeral, and from that point on Neil pretty much refuses to communicate how he’s feeling, and Gosling does everything to keep all of that inside. It is only in the climactic lunar sequence when we see Karen’s bracelet for the first time in two hours that we know it was simply too much to discuss. We can understand that implicitly, and Chazelle and Gosling collectively hold it inside of us until it is time to literally (if not figuratively) let it go.

Is it odd to hypothesize about what a real person is thinking in their career and life choices? Probably. Am I turning Ryan Gosling into a character in my own writing as a way of getting across something I have been thinking about a lot independently of Gosling’s career? Unequivocally yes. Do I feel bizarre about this? A little. But the film I started this piece talking about is Gosling himself and Damien Chazelle doing pretty much the exact same thing with one of the most famous Americans to never hold the presidency. This might be wrong, but only the same kind of wrong being perpetrated by the same person I’m writing about, so I’m slowly coming to terms with it.

The last scene of First Man, the scene that prompted the man near me to say “…what?” comes in quarantine, after Armstrong has returned to earth. The film lets us know that things weren’t perfect in the old Armstrong homestead before going into orbit, but now that Janet and Neil are together again, Neil reaches out to touch the pane of quarantine-thick glass in front of him. You can look at the person you know better than anybody else in the world, and there’s still something there you can’t quite get through.

I have been writing this essay for over a month now, and I can’t quite say it’s finished because I can’t quite say it comes together properly. There is something missing, something I couldn’t find in research, and now I am out of Gosling movies to watch and Gosling profiles to read. There is nothing more to be done. I can keep trying, but occasionally you have to realize that the question you’re asking yourself may be unanswerable.

Eventually, you realize this. You try to reach, and you either keep trying to reach the same way or you find something new to reach out for, a new thing to occupy your days. If you can get close to the glass, you have to count it as a win. After all, once you get there you’re only going to turn around and see the place you came from taunting you from a distance that used to be right under your feet.