Alex writes about directing, and why he gives directors so much credit.

“This is probably a terrible idea,” he said as he sipped on his drink, knowing all well that the probabilities were probably even less in his favour than he assumed.

“But let’s do it anyway.”

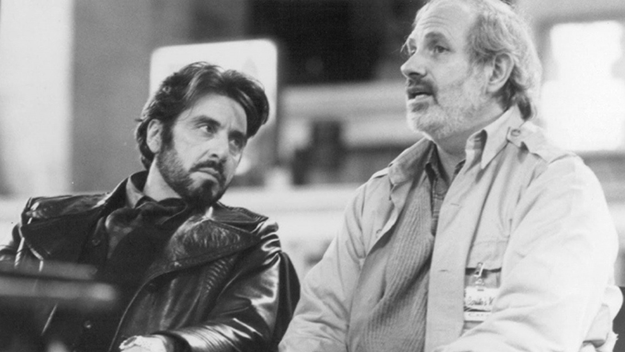

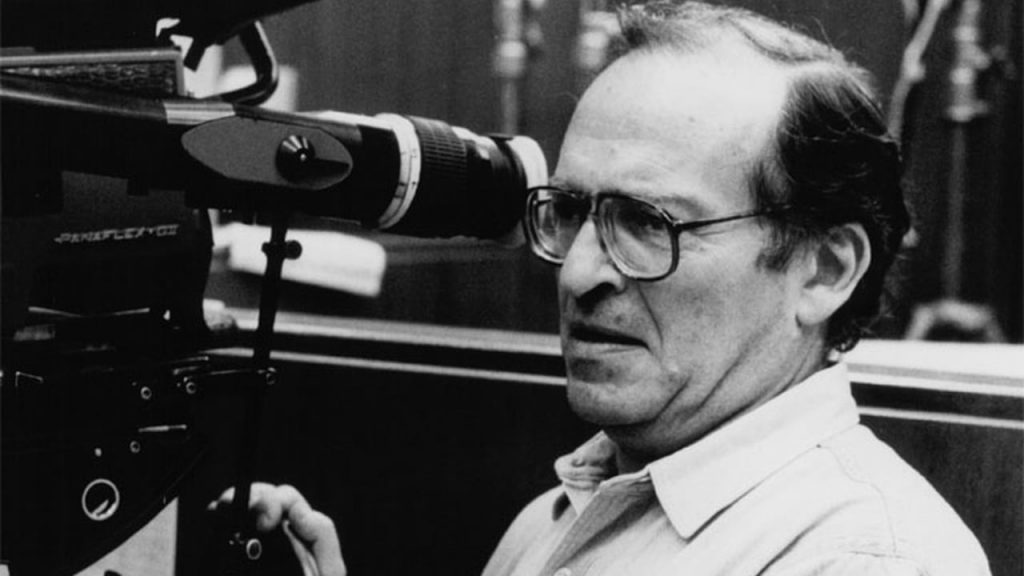

There’s a moment in Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow’s film De Palma, where the Notorious BDP is talking about a sequence he had designed for use in his 1993 film Carlito’s Way. For this scene, De Palma went to incredible lengths to make sure everything was just right when everybody eventually got on set. He storyboarded the shot, and he did a pre-visualization in an unnamed computer program that was uncommon for non-effects shots. Brian De Palma knew exactly what he was going to do, and how he was going to achieve it. He was a man with a plan.

In the sequence, Al Pacino – as Carlito – is being chased by a group of people for reasons I don’t quite recall. I do, however, recall that these people definitely wanted to murder Carlito, so this was most certainly a chase with stakes. Said chase began on a subway train, but was to continue off of it, as Carlito stepped off the train. In De Palma’s idea, Carlito was to exit the New York City subway to continue trying to evade his eventual murderers. The subway station they had planned to use for Carlito’s train exit and continued evasion was the subway station underneath the World Trade Center.

The day before the sequence was to be filmed, a truck full of explosives was driven into the World Trade Center. Everything had to be rethought; all planning was for naught.

In the documentary, Brian De Palma uses this anecdote as a comment on the role of director: you see what you want, but there are a million outside forces that you can’t anticipate waiting to change the course of your ideas. Obviously, the Carlito’s Way example is a particularly uncommon example, but the point remains. Having an idea in your head is nothing; making some version of that idea into a reality is what makes you a director.

(Quick interjection: before I continue, I want to make a couple of things as clear as possible. One, it is impossible to direct anything without a good crew. Whenever directors talk about their film, they never say “myself and the crew” because that would get tiring and repetitive. For ease, I will do the same when discussing my own work.

Also, and most importantly: I am not comparing myself to Brian De Palma. That would be idiotic; I don’t have the ear lobes for it. I am definitely not comparing myself to any of the other directors I will mention either. The only thing I have in common with David Fincher is a general disdain for the world and an appreciation of Brad Pitt. To say I am not on the level of these directors would be a tremendous understatement, and I definitely don’t see myself as somebody that even has the capability to become their creative peer. I would be shocked if I ever even tried to make a short, let alone a feature film. I am fine with this. The closest I will ever come to making a film is tweeting at Ryan Fleck. I do not have a filmmaker’s dedication. I am a mere layman. That said, it is true that I am a layman with more directorial experience than most of my fellow laypeople. So, with all necessary qualifiers mentioned, we travel onward.)

Professionally, I am a freelance video producer, which is to say I make my bones providing various companies with various types of video projects to get their various messages across. In making these videos to (fundamentally) help peddle product, I do pretty much everything: I hire the camera operators, I book the space to shoot in, I direct the shoot on the day, and I edit the eventual video. I frequently double as my own director of photography. I am like Steven Soderbergh, if Soderbergh was a capitalist pig that used too many pronouns in his writing.

The reason I do everything is the same reason everybody in my field should do this: when you do everything, and you have the ability to do everything quickly, it is simply the smartest financial reasoning. I can work quicker, so I can work more. And when it comes time to actually do something creative, this Swiss Army Knife mentality does the same thing for your more personal projects: it keeps your costs down. Rian Johnson edited Brick on his PowerMac because his debut had a budget of less than half a million dollars, and he could save that money for film stock instead. (In the past, the only reason I’ve been able to afford the production crew I want is because I don’t have to pay an editor.)

When I haven’t been capitalizing on my capitalistic tendencies, I sometimes pursue creative pursuits of my own, and my two degrees of separation from a band that doesn’t suck has allowed me to make a bunch of music videos. I have the emotional fortitude to watch exactly one of them without wanting to vomit.

This is not a good batting average. The jury is in, and they have rendered a guilty verdict on 11 counts of being a terrible director, despite the fact that I am (technically) an award-winning director.

Invariably, the process goes as such: I am tasked with listening to a song and proposing a handful of video-based ideas this song gives me. Those ideas are sent to the band, who then decide whether or not these ideas are hot garbage. Much conversation is had, and much planning is done. We talk about how much money we have to spend, and we talk about whether or not anybody can be paid. I storyboard some shots, the artist tells me all of their ideas, and then we combine the two. Finally, we pick a shoot day.

When that day eventually comes, all of that planning is pretty much useless. We deal with realities that come with low budget productions: somebody that was supposed to show up at 8am will be arriving at 11:30am. The space we have simply is not conducive to the camera moves we had planned, because we couldn’t afford a rehearsal day with the crew to solve these issues. Our gaffer doesn’t have enough diffusion to adequately control the sunlight in the way we had wanted. The space we’re shooting in turns out to be a bong water-soaked porn dungeon, and nobody brought any Purell.

Sorting out all of these issues is taking us time that we already didn’t have enough of to begin with. A production assistant has to go buy lighters and hand sanitizer, while we have to move the shot list around to take care of all the things we can get without the person that will be arriving three and a half hours late. We simply have to deal with the fact that we’re going to be in a porn dungeon for the next fourteen hours.

I have never left a set without enough to get a completed video. What we are able to get, however, is almost never what I wanted. If this wasn’t my profession, I am certain I would drink less.

On the podcast, James and others have told me that I constantly sound like I give directors too much credit. I have also been accused of this on rooftops, at parties, and while grilling kabobs. That said, it is an unquestionably true accusation. Everybody is right. But it’s true because, again, I know (slightly) more about directing than James and the other people in these aforementioned scenarios. I don’t mean that to put myself in an elevated position, merely an informed one. Again, I am a layperson, but a layperson with a certain kind of uncommon life experience.

Admittedly, when I watch a movie, I care more about the direction than anything else. A poor script can be immaculately directed and I would still like it; this explains my appreciation of Terrence Malick’s To The Wonder. Most people seem to watch cinema as books committed to film: the plot, characters, and resolution is what matters. Which is true. All of those things matter, and in the best-case scenario I find them interesting to think about as well. But I’m always just a little bit more interested in what it took to get everything onscreen in a functioning capacity.

When I see a really impressive set up, I know what must have gone into it. It can’t have possibly been exactly what was planned. In the opening pages of Sidney Lumet’s book Making Movies, he mentions how he once brought up a particularly gorgeous Kurosawa shot to the auteur himself.

“I once asked Akira Kurosawa why he had chosen to frame a shot in Ran in a particular way. His answer was that if he’d panned the camera one inch to the left, the Sony factory would be sitting there exposed, and if he’d panned an inch to the right, we would see the airport – neither of which belonged in a period movie.”

By the time we’re watching Ran, we can’t see the Sony factory. That’s the point. But some of us are better at imagining that there might be one just off the edges of the frame.

Editing is frequently a difficult process as well. When you’re on set, you are limited in what you can do, but when you do come up with a feasible idea, you can still attempt it. At least at that point, writing is still a possibility. When you get to editing, you are faced with a hundred thousand piece puzzle, and you don’t know what it’s supposed to look like at the end. You are still shaping the final product, but you can’t create any new pieces. You’re still writing, sure, only now you’re working with a predetermined, frustratingly small satchel of word tiles.

Often, filmmakers find themselves in trouble in the editing room. Paul Thomas Anderson couldn’t figure out how to make Punch Drunk Love work in editing for over a year; Spike Jonze was showing an overlong version of Her to anybody that would watch it, trying to figure out how to properly structure the final film. Both of these movies ended up being very good; neither of them even gives off the look of something that came together through editing. But they were not without their problems while they were still being made.

Frequently, there are only so many options to make an engaging finished product. Your initial idea simply doesn’t feel the same cut together as you assumed it would, or it doesn’t work because you timed everything out wrong on set. In the most recent music video I edited, the order of events in the final product was changed simply because the footage for the first verse took more time to run through than anticipated, and the second verse allowed us the time we needed for it. It took me months to see this is the way things would have to be, the way things always should have been in the first place.

The fact that anybody can direct a functioning film is pretty fucking impressive. It’s a difficult job, and anybody that can pull it off is cool in my books, even if the eventual film sucks. (I admire you, James Cameron, even though I hate most of your movies. Uwe Boll is a lunatic, but you can’t knock the persistence.) When I really love a movie, though, is when the job is most impressive. When Christopher Nolan is able to actually make the labyrinth of Memento come together, it’s a marvel. David Fincher’s accelerated view of Facebook’s founding is a truly impressive success. These people have to dedicate at least a year of their lives to putting together something we will consume in two hours and (in all likelihood) never think of again. Even when somebody makes an amazing film – Derek Cianfrance’s The Place Beyond the Pines and Kenneth Lonergan’s Margaret come to mind – there’s still a good chance nobody will even fucking go see it.

Whatever hoops somebody has to jump through to direct a film, I applaud their calf strength, their refusal to never stop never hopping. Because you are performing a fool’s errand, fair director, and yet you do it anyway.

When it was eventually filmed, the climactic sequence of Carlito’s Way was changed. De Palma had Carlito escape to Grand Central Station to catch a train instead of exiting at the World Trade Center. And that new, altered version of the sequence that ended up in the film is the only part of that movie that I loved. I don’t remember why a grab bag of thugs was chasing Carlito, but I damn sure remember that elongated Steadicam shot. Brian De Palma’s original idea couldn’t have worked due to forces outside of his control, but he made it work anyway.

That’s the core of directing: having an idea, realizing that idea can’t work as well as you want it to, coming to terms with that, and making your backup work anyway. The world is never what you want it to be, because the world is never truly yours.

“It’s always a terrible idea,” he reminded himself. “But let’s do it anyway.”