This is part 2 of Alex’s article about teen movies and MTV reality shows. If you missed the first part, it’s right here.

Director Steven Soderbergh (Traffic, Che, the Limey, Ocean’s Eleven, etc) has had an interesting career, to say the least. Never one to attempt the same thing twice, Soderbergh has found that he is running out of ideas and has publicly contemplated retiring from film within the next couple of years. His main concern as a director isn’t narrative; Soderbergh is far more interested in how the story is told than telling the actual story itself. As such, his movies rarely look similar to each other, nor are the stories told in a similar fashion. Even the Ocean’s Eleven series, which was a highly commercial and mostly-coherent trilogy, used three radically different visual styles. In a recent interview with Studio 360’s Kurt Andersen, Soderbergh was asked which filmmakers he admires.

“That sort of leads us into a question of theft, which for every artist is a really important question. Stealing is necessary. The way in which you steal, though, is very important. You need to… it’s like going over to somebody’s house… if you’re going to steal something out of their closet, you need to act as though you now own it. You’re not giving it back; you’re going to wear it as though it’s yours. And you need to sort of take control of things you see that you feel now need to become a part of you.”

When Soderbergh discusses leaving filmmaking (and let’s just assume for the sake of argument that he really will retire), he doesn’t sound like he will miss it. His work ethic is remarkable, and one only has to look at the short dates between his movies to see that. Soderbergh seems to be running out of formal experiments to attempt, and says he would rather retire than tire of film. He mentions that he is no longer excited to get in the location scouting van, so he’s going to leave that to younger directors who are still excited to do just that. Soderbergh likely is aware that many of these younger directors will look to his work for inspiration, and he is also likely content with the idea of younger filmmakers repurposing some of his stylistic ideas.

Sports journalist Jackie MacMullan published “When the Game was Ours” in 2009, a book she co-authoured with Larry Bird and Magic Johnson about their rivalry throughout their playing careers. In a recent interview with ESPN’s Bill Simmons, MacMullan details how that upon handing her manuscript in to her publisher, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt immediately dished it off to HBO as a piece of research for a forthcoming documentary, not unlike one of her co-authours would do on a fast break. MacMullan was initially horrified by this, as she was to have no input (outside of a filmed interview) in the documentary about the rivalry, but she details to Simmons how her opinion eventually changed. Once the documentary Bird & Magic: A Courtship of Rivals aired in March 2010, MacMullan’s book had been published for months, and it received a healthy jump in sales due to the HBO film. MacMullan’s version of the Bird & Magic story was losing interest, but somebody else’s interpretation of it, based on MacMullan’s book, gave her own work resurgence.

Pablo Picasso’s quote “art is theft” leads off David Shields’ book “Reality Hunger: A Manifesto,” in which Shields compiles a variety of quotes to form a whole piece of work. While he adds his own notes along the way and alters some of the quotes, it appears that only about 40 percent of the book is original writing by Shields, whereas the rest was compiled (with some quotes also being altered slightly, such as Picasso’s). Shields’ intent appears to be to show that all art is in some way related, and that the questions of artistic theft should be considered more an homage than anything. In Shields’ view, once a publication or film or song has been released, it is his for the taking (and altering). He numbers each quote throughout the book and lists the original writer in the appendix, but he says that this only happened at the persistent requests of his publisher; his intention was to not attribute the quotes to anybody.

In my university career, I always felt that any essay I wrote was mere quote compilation (albeit with more sourcing than Shields). I was barely doing anything other than compiling information, and adding in what this information said to me either personally or as it pertained to the subject. No matter the topic, be it Michael Bay, Saturday Night Live, or Bioshock (I essentially majored in being lazy), I always felt like I was merely contorting somebody else’s idea into what I wanted it to say. I might draw a professor or reader’s attention to something they might not have otherwise known with a quote I found, but the most interesting words in these essays were never my own. I was just extending the ideas of other people to a reader who perhaps would not have come across them otherwise. I feel that way about this article as well. And this is why I have never been able to grasp why some people don’t like sampling in music.

I have been a hip-hop fan to some extent since I was a toddler, when Run-DMC’s “Christmas in Hollis” was my favourite fucking thing ever. The beat to that song was built on Clarence Carter’s 1968 song “Back Door Santa,” a holiday song as entertaining as its title is unintentionally funny to Adam Sandler fans. The thing about Christmas in Hollis was that it introduced me to a Clarence Carter song I likely would never have put any thought into otherwise. When I heard the song used in the Arnold Schwarzenegger film Jingle All the Way in 1996, 10 year old me instantly recognized it as the sample Run-DMC had built Christmas in Hollis around. Without sampling, it is conceivable that I wouldn’t even know who Clarence Carter is, but now I’m linking you to his Wikipedia page. And two decades later, Christmas in Hollis is still being used in popular television shows like the Simpsons, the Office, and Chuck. I may not be running out to buy any of Carter’s records, but I am aware of his music only because it was sampled. For any artist in a popular medium who is not constantly lying to themselves, having people be aware of your artistic output is the most important aspect of creating it.

People who are against the idea of sampling are quick to cite the financial aspects of the situation. When a horn break is lifted from a Clarence Carter song, if nobody is being paid for that, somebody will be upset. A landmark lawsuit against Biz Markie in the early 90s proves this. But nobody gets paid when Quentin Tarantino turns a collage of other movies and pulp novels into what critics dub an intertextual masterpiece, and Picasso’s estate doesn’t see any money from David Shields quoting him. Chuck Klosterman certainly won’t see a dime from this article. People seem to be okay with unlicensed sampling, so long as it is done the right way. But what is the difference?

“Those who study film and literature are often taught to recognize intertextuality, as it helps them to understand the text. In these art forms, it is up to the reader/viewer to distinguish what aspects of the work are intertextual, and therefore acknowledge the original text.” This is friend (and voice of the MacGuffin Men) Emily Vella writing in a paper about fair use and copyright issues inherent in sampling. She argues that there is little difference between sampling in film, literature and music, outside of the amount of money that can be made from protecting copyright in music. When an artist is sued for use of an “illegal” sample, it is common for the actual sampled musician to receive no money from the lawsuit. Whoever owns the publishing to the music gets paid, and often that is not the artist.

Years after using a vocal sample from then-rival Nas, Jay-Z boasted that “[Jay-Z] knows who [he] paid god, SearchLight Publishing.” The song where this line occurs is Jay-Z’s diss track “Takeover,” which itself legally samples the Doors’ “Five to One.” I don’t know if the Doors themselves saw any money from “Takeover,” but I know the Lafayette Afro Rock Band saw nothing from Jay-Z sampling them for his 2006 single “Show Me What You Got.” And in a case outlined in Emily’s paper, Funkadelic musician and rainbow hair braid pioneer George Clinton saw no money for an N.W.A. sample of Clinton’s “Get Off Your Ass and Jam.” Only a “sample-troll,” a publishing company that makes money through copyright lawsuits by acquiring rights to music, saw any money in these instances. And often, these sample-trolls acquire these rights through shady circumstances; Clinton theorizes that the rights for his song were more or less stolen from him. Despite this however, Clinton still favours sampling, calling it “a way to get back on the radio.”

Many of the most popular and culturally relevant media products are now extremely postmodern, and use sampling in one way or another to get their ideas across. Inception was a product of a lot of sampling; it is telling that its themes are succinctly summed up by one line in the Matrix. Glee combines the musical with the teen movie formula, with an infusion of the cultural fascination with karaoke. Community, while significantly less popular with the masses, is often cited by critics as one of the most creative and compelling shows currently on network television while being built almost entirely on referencing other television shows and films. Yet the only one of these products that has drawn any real controversy is Glee, and that controversy has had little to do with the re-possession of the songs in the show; the controversy almost always seems to be based on the way teen sexuality and drug use is portrayed (which actually happen to be the aspects of teenage life that Glee does portray interestingly). Essentially, in the case of Glee, mass culture is okay with the new versions of Britney Spears and Journey songs, and that seems to be because typically the songs don’t change all that much. But even in the case of Glee, these songs are being altered and modernized to fit the format of the show, and culture still seems to not only be okay with that, but adore the show for it.

Much like the Breakfast Club summarized the general perception of the youth of the mid-80s, or the inaugural Real World season did for the early 90s, Glee will one day be looked at as a representation of things that were once interesting to mass culture. A 24 year old in 2037 probably won’t like Glee per se, but they might be fascinated by what it says regardless. The presentation of teen sexuality and drug use will seem outdated by then, but it will represent what was controversial decades ago. And when sampling is eventually more widely accepted in pop music, perhaps Glee’s popularity will have even played a role in that shift.

Sampling is, essentially, looking back on an older piece of media. Regardless of whether that time is in the recent past (MacMullan’s book), or further back (Clarence Carter’s music), it is extending that artist’s influence. It’s N.W.A. getting George Clinton’s music back on the radio, or Community reminding us that the 1981 movie My Dinner with Andre exists. This idea is not applied only in media products, however, but in human interaction as well. Like every paper I wrote in undergrad was a collection of information samples put through my own filter, so too are my day to day conversations. When I’m talking about the positive aspects of Lady Gaga, I am merely adding my own spin to Chuck Klosterman’s thoughts on the subject. When discussing the negative aspects of the Fame Monster, I’m sampling my friend Emily’s opinions into my own. And I don’t think that this action should necessarily make me feel like the Shame Monster.

Early in this article, I quoted Steven Soderbergh. I did not, however, give you the full context of Soderbergh’s words; I left out a sentence. Here is the quote again, with the sentence I previously left out now present and in bold.

“That sort of leads us into a question of theft, which for every artist is a really important question. Stealing is necessary. The way in which you steal, though, is very important. You need to… it’s like going over to somebody’s house… if you’re going to steal something out of their closet, you need to act as though you now own it. You’re not giving it back; you’re going to wear it as though it’s yours. And you need to sort of take control of things you see that you feel now need to become a part of you. And so that’s a long way of saying I’ve been as influenced by things I haven’t liked, or haven’t responded to, as I have to things I have responded to.”

Soderbergh means this as it pertains to his filmmaking style. He goes on to detail how just before he was to shoot his first film, Sex, Lies & Videotape, Soderbergh saw a terrible movie dealing with similar themes as his own script. What Soderbergh took from that screening was essentially a blueprint of how to not make his own film. Soderbergh meant the point to be taken as how he talks about his work, but it is not particularly difficult to apply that to pop culture affecting our day-to-day lives.

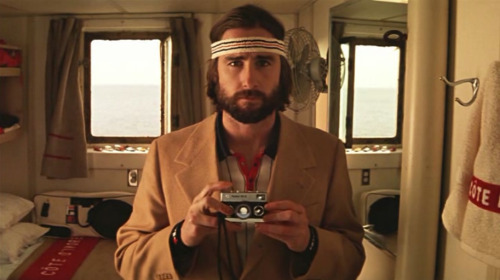

MTV’s target audience no longer knows a world without MTV reality shows or teen movies. We have grown up experiencing construction after construction, and these media products build on each other over time. Jersey Shore is just the Real World: Seaside, and John Tucker Must Die is a version of Mean Girls where Cady, Janis and Damien are more adept at using social media. And like these products build on each other, we build ourselves on them as well, again extending the life of media that resonates with us. While some might purposely apply aspects of a certain product to their own life, that person is certainly in the minority. The Soderbergh quote implies that we need to be in control of how products influence us, but it is nearly impossible to really do so in practice. A nameless, chubby friend of American Teen’s Hannah dresses exactly like Luke Wilson’s character in the Royal Tenenbaums, seemingly every day. At such a young age, he is unlikely to have a conscious reason for dressing like a homeless tennis enthusiast, but he does so anyway. Both he and Hannah fit perfectly into their predetermined character types, and that type is instantly noticeable through the media they have associated themselves with. Something about the Royal Tenenbaums affected him, much like MTV reality shows and teen movies affected Hannah. And even though I didn’t particularly like it, something about American Teen must have affected me. I just might need a decade or two to sort out what that was.