Alex writes about Wendy, Benh Zeitlin, and Beasts of the Southern Wild.

Let’s go back to early 2012. A director releases his debut feature, a feature that begins as a widely adored and appreciated Sundance hit. It is released to the general public in the summer of that year, to further acclaim and profits that greatly outweigh what the film cost to make. Listening to people walking out of the cinema I saw it in, all viewers sounded resoundingly positive. In the winter, it would be nominated for four Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Actress, and Best Director. It was a type of success anybody would accept. And yet its director didn’t release another feature for eight years. How does this happen?

The picture in question, to those who have yet to figure it out is Beasts of the Southern Wild, a film that I can assure you was beloved at the time of its release but has since been widely forgotten. This is not uncommon: a look at the other nominees for Best Picture that year reveals a collection of films that had their time in the sun, but whom nobody really talks about all that much anymore. This happens at each Academy Awards, or each year in general: there are always myriad successes, but only one or two films each year can really stick in the collective consciousness for longer than an award cycle. In order to do that, your film has to be truly beloved by wide swaths of people.

My recollection of my 2012 review of Beasts of the Southern Wild was something along the lines of: “these special effects are intriguing,” “holy shit does this music bang,” “this sound mix is off the charts,” “that little girl is great,” “does this movie have a plot,” and “are we watching another entry into the world of indie Malick ripoffs?” My companion and I followed the film by going across the street to drink the cheapest beer on the menu and eat salads that were served in bowls made out of fried dough.

“I liked it,” said my friend who has and shall always retain the ability to translate my longer thoughts into shorter, concise ones. “It was a nice story of a father and his daughter.” I could tell from how she said it that she would probably never think about this film again, and I could tell from my reaction to this that I certainly would. I saw Beasts of the Southern Wild two or three more times, because no matter what you say about the film it is an exciting stylistic exercise with a manageable running time, sliding into the slot for “short movie I can see to fill the gaps between two other movie screenings.” I listened to the soundtrack a lot, while writing and while cooking and while walking into screenings of Beasts of the Southern Wild. (Before my second screening was through, I recall thinking, “Is this movie good, or do I just like the music?”) But the day of the Oscars that year was probably the last time I thought of Beasts of the Southern Wild for years.

When Benh Zeitlin finally released a new film earlier this year, Wendy, I was scoffed at for suggesting I was planning on going to see it. Of course, I didn’t end up going, because I planned to see it on a Thursday. But on Wednesday, Rudy Gobert tested positive for COVID-19, and then borders closed, and I had groceries to stock up on. But I thought a lot about why my friend would think it was silly of me to want to see it.

“It’s directed by the guy who made Beasts of the Southern Wild,” I said, “And I kind of feel obligated to see the follow-up.”

For reasons I honestly can’t even put into words, I felt compelled to watch Beasts of the Southern Wild this past Friday night. I needed a guaranteed win, and I knew if nothing else, this short movie with an absolute banger of a score* would get me home. Watching it in 2020, I noticed a few new things that weirdly I have no recollection of hitting me in 2012. Less than ten minutes into the movie, I knew where all the 2012 success came from: this is a Terrence Malick film poured through a Spielbergian strainer, removing all the fat, upping the broad emotions, and telling John Williams to make the audience bawl. It’s a short (all later period Malick movies are too long, I’m told) movie about a kid (as opposed to adult children played by movie stars) and her father (as opposed to lover), there are countless gratuitous handheld shots of nature (this was left unchanged), and the music is overpoweringly emotional.

*I truly cannot make this point loudly enough. I think if this movie had a less exceptional collection of music running underneath it, the collective reaction would have been entirely different.

Zietlin is not the first person to take Malick’s ideas and translate them to a wider audience, of course. These things are rampant; Malick kind of rewrote Hollywood film language, and people took little bits of it and injected it into their own work. David Gordon Green is the Sundance copycat, with his George Washington being a bonafide Terrence Malick covers album. You can see it in Michael Bay’s work, especially the later films, and you can see it in literally every indie movie set outside of a metropolis (and most within as well). Christopher Nolan remains the king of the Malick thieves, filling his movies with brief handheld cutaway shots to signify a different time or a different memory. Malick will be remembered as the Velvet Underground of filmmakers, the man whose work was widely ignored by everybody but filmmakers, and ridiculously influential to those who picked up a camera with a compulsion to tell a story.

Beasts of the Southern Wild has a lot of conflicting ideas in it, and I felt the return of a lot of my own conflicting ideas from 2012. I still feel like this film might be at least vaguely racist, although I couldn’t put the why into words in 2012, but it mostly revolves around a white filmmaker making a film about predominantly black characters. Although, of course, Zeitlin and his team encouraged those actors to have a lot of agency over their characters in the production. When the film was released, there was much talk of Zeitlin’s Court 13 production collective and their collaborative approach to filmmaking, a collaboration that reached all aspects of production.

“There’s so many facets that you can really bring everyone you know together, who you care about, who’s talented, who has a good heart, and they can find their way into creating something good for the movie, provided you allow the individuals working on the film to have agency and to be able to express themselves, which I think is the hardest thing about when you go to work on a traditional set,” Zeitlin told Scott Foundas in filmcomment in 2012. “The creative hierarchy is incredibly regimented and the people actually touching the stuff that ends up on screen don’t have any love for the things they’re making. Even if the designer does, by the time it gets to the person actually painting that or sewing it together, there’s no feeling in that actual task.”

Zeitlin’s approach was to listen to everybody, writing and rewriting dialogue to fit actors after improvisation sessions, and to listen to any idea that might come up during production. (Again, not all that dissimilar from Malick’s style of filmmaking, or Cassavettes, another Zeitlin touchstone.) This feeling of freewheeling creativity permeates the film, and Zeitlin’s job with his post-production team was to (arguably) tie all the exploration together.

I thought a variety of things during my recent screening of Beasts, but I mostly thought: say what you will about this film, but I’m excited to see what this guy can do next. And he had proven he could do a lot with a little. For whatever reason, filmmaking economics don’t always allow for somebody who can do a lot with a little, even when “a lot” translates into four Academy Award nominations. It was viewed as a lark, it seems.

Let’s move back to earlier in 2020. Zeitlin’s new film, Wendy, has its debut at Sundance to little to no fanfare. Despite how closely (I think) I follow American cinema, I did not know the film existed until the day before it was released in a nearby theatre, and the pandemic has done nothing to increase the film’s reach. I would have seen it in theatres but then, of course, you know.

Watching Wendy is a different experience than Beasts of the Southern Wild, if only because the Zeitlin style of freewheeling indie bombast is no longer new to those of us who saw his debut. The styles of each film are the same, with loud music and unconnected voiceovers paired with footage of children running around and generally being adventurous. As all reviews and/or pieces about the film must claim, Wendy is a reimagining of the story of Peter Pan for the Sundance set, which is just about the most “Spielberg by way of Malick” thing you could possibly imagine.

There are moments where Wendy is as impactful as Beasts of the Southern Wild, just as there are moments in Wendy that are bland and stale (not unlike Beasts of the Southern Wild). The main difference is that, with Wendy gallivanting for approximately twenty minutes longer, the gaps between the good and bad moments are larger, making an already disconnected style feel even more disconnected. With a movie that runs 93 minutes, like Beasts, you power through the two slower minutes before Dan Romer joins in to blow out your eardrums, but with Wendy you often have to stick with what is a less engaging scene for an extra couple of minutes. This is not an argument to make all films shorter, more that the runtime of Wendy simply allows the viewer to meditate on its missteps more, in between the moments of triumphant adventure. And there are some truly beautiful moments in Wendy. From the introduction to Wendy herself and the film’s title card*, to the out of nowhere emotional wallop that comes in the montage after Wendy and her brother return home to live their own adventures, the film never goes too long in between instances of jogging your memory to remind you of Beasts’ finer moments.

*Which, it should be noted, is incredibly similar to the opening of Beasts.

The highlight of the film is the way Wendy depicts twin brothers Douglas and James adapting to life after Douglas is believed dead. After running off to the island where the majority of the film takes place, a place where a volcano named Mother stops its inhabitants from aging, Wendy and her brothers go swimming amidst the wreckage of a sunken boat. Douglas hits his head, starts bleeding, and appears to be lost underwater. As time passes without his brother, James watches his own right arm grow old, eventually demanding Peter cut it off. James becomes old, bitter, and lost, crossing the barrier to the less populated part of the island, where those who feel cast off by the island society go to wander meaninglessly. When Douglas returns late in the film as a still-young boy*, James and Douglas are able to look at themselves older and younger simultaneously. They are able to see what the world has done to James, and what it has yet to do to Douglas.

*Out of nowhere, and with seemingly no explanation, but plenty of things in this movie are totally unexplained.

Now, writing this all out makes the movie sound deeply terrible. And it might be. The highs are very high, but they are spaced out, and there are many more lows. But the moments where Wendy hits its peak are glorious, and this is one of those moments. The film wordlessly shows us the twins, one old and one young, in a graphic match to a shot from when they first arrived on the island. Instead of the whole world being in front of them to play with and explore, however, now James has been overcome by the darker elements of it. He experienced a life without what he needed to be happy, and he can see a younger version of himself with that whole life left in front of him, the younger version looking back at him, silently hoping to avoid the same mistakes. Because this is still technically a Peter Pan story, James has fashioned himself a hook to replace his hand, gathering his fellow Olds to fight back against the island and Mother.

The film sprints to its end, with Wendy and Douglas rushing home to their mother, and a montage of their lives from there on out begins. Wendy has her own child, who is eventually taken away by Peter on a train in the middle of the night, a train Wendy rushes to chase after but can’t keep up with. She knows her own daughter needs this, and so she lets it happen. (It is weird to see a film end with a mother being okay with her child being kidnapped, but this is how Zeitlin’s world works, I guess.)

Again, watching this film and thinking about it and (especially) typing it out all make Wendy sound like nonsense. And, as I keep saying, it might be. But one truth of it is that I love how this nonsense feels, even when I am occasionally a little bored with it. Wendy plays like a movie steeped in a type of freedom filmmakers would pine for, and it is able to feel as free as it does specifically because Zeitlin doesn’t need the Hollywood infrastructure to make the films he wants to make. By keeping his work strictly independent, he is able to do what he wants (at least for now). Wendy’s lack of success might make his next adventure slightly more difficult to fund, but he found a way to make Beasts of the Southern Wild happen, so I have no doubt he’ll be able to do the same again.

The lack of cohesive structure in Zeitlin’s films creates a high risk, high reward sort of proposition for the viewer. Either this montage will work and the viewer will be exhilarated, or this montage won’t work and probably none of them will and oh no now that guy’s snoring in the fifth row. I have experienced this a lot of times; I keep referencing Terrence Malick’s movies in this essay and others because I am one of his bigger fans. I have seen people nod off during montages I would describe as “perfection,” and I always understand why they do. This movie may be terrible, but – while I may lack the words to properly explain why – it is most certainly for me.

Something that has bothered me (and surely always will) is the impossibility to describe what about a song is so exciting to me. Much of my favourite music is instrumental, and even an appreciation of something like Run the Jewels requires me feebly explaining ethereal concepts that convey some sort of feeling. Similarly, Zeitlin’s two films are so strongly tied to their scores (composed by Zietlin and Dan Romer). Wendy and especially Beasts often feel more like songs than movies, with ideas tossed to the audience and then discarded, because the mechanics don’t matter so much as the feeling they convey. The specifics are meaningless, because nobody is going to remember the exact lyrics anyway. All that matters is how it feels.

Before leaving the island, Wendy joins her fellow inhabitants, both young and old, in singing a chant to Mother. They are all singing in unison, in hopes that what they call out will be picked up and a volcano will erupt (or whatever the actual plot is). It doesn’t matter if anybody can hear them though; hearing the call never mattered. All that mattered was still being able to sing, in the hopes that somebody will hear it. But either way, calling out means something to its singer.

Both of these films might be bad, or both of them might be good. There’s simply not much of a difference between them beyond the runtime. The pervasive feeling I have, that publishing this will put a button on my desire to watch either of them again, leads me to believe they’re closer to bad than good. But I enjoyed watching them; Beasts was an interesting experience in 2012, and Wendy was a different kind of interesting experience in 2020.

There are always going to be people who create something that seems new and exciting, and occasionally that new and exciting thing might actually be an old thing repackaged in a new, exciting style. That, along with an ad campaign that works, will lead a portion of the masses to your film. You will bask in your success for as long as it lasts, always concerned it might disappear in the blink of an eye.

Those same creative people might then need a little bit of time to create the next new and exciting thing. By then, of course, the world might have changed, because the world is always changing (and seems to be doing so at a much more rapid pace than was done in 2012). The singular truth that will remain, however, is that the gatekeepers of Hollywood will follow the money, and if the new idea doesn’t seem like something that will make money (and the previous person who gave you money is either bankrupt or no longer wants to give you money), then you’re screwed. You are left to your own devices, to create a world people may or may not want to be a part of. It doesn’t matter. It was never meant for them, anyway.

]]>In Survivor: Winners at War, a lot of things remain unclear on a week-to-week basis. After being hit with an extortion disadvantage that requires him to pay six fire tokens, Tony has to borrow three tokens from three different tribe mates to make the payment. In the following segment, Tony immediately wins two tokens at the immunity challenge. Which of the two people did he pay back? The show doesn’t mention it. When Parvati and Natalie get their six tokens from Tony, the show doesn’t tell us if they split them evenly, or what their strategy was for using them. This is one of the many times this season when the game is overrun by information, and the show simply doesn’t have time to tell us everything that’s going on.

Well that’s exactly what happened in my head while writing this. These are extra pieces of information that I think are interesting and important to the history of Survivor, but that I simply didn’t have room for in what was already an 8000 word piece that ended up in my book. I don’t know why you’re reading this, but thank you for sharing my obsession.

Parvati’s True Manipulation

Survivor is, to put it mildly, an extremely conservative show. It is aired on the most conservative broadcast network, and often plays into outdated historical binaries (like Heroes vs. Villains) that make little sense in the modern age. After twelve seasons of being criticized for a lack of minority representation throughout the casts, Survivor’s response was to start its Cook Islands season by splitting up its four tribes by ethnicity, a decision that was lambasted in the press and questioned by its own contestants, including eventual winner Yul Kwon in his first confessional interview, and Parvati Shallow in hers.

“Different ethnic groups,” Parvati says. “I mean is that… kosher? I don’t know.”

Cook Islands is Parvati Shallow’s first season, and it is not her best-played season by any means. Her strategy is initially to play on her charms, and use her flirtatious personality to build an alliance to protect her that she can then turn on later in the game. When her alliance loses its dominance, Parv’s fate is cemented, and she comes in sixth place. Like so many skilled Survivors before her, she gets unlucky.

But the show also does her a disservice, and the way she is edited feels like it views her as a one-dimensional flirt. Since Parv is a traditionally attractive woman, the show tends to hone in on moments when she is cuddling up to fellow contestants, and features multiple slow close-up pans of her body as she lies in the sun. Later seasons would prove this was all a part of a larger, more skilled plan from Parv that the Survivor producers simply couldn’t see at the time. To them, she’s simply there to fall in line as one of the season’s “hot chicks.”

When women are bathing in Survivor, particularly early seasons, the way the camera lingers on their bodies is (obviously, this is a reality show) pretty gross. Most traditionally attractive women on the show are treated as little more than that, and that includes the winner of season six, Jenna Morasca. Sometimes these women play into the roles the producers throw them into, as Jenna and Heidi do when they strip naked in return for chocolate and peanut butter, but they only do so because Jeff Probst is able to turn their jokes into a real offer in the middle of a challenge, and egg them on to get them to accept it.

In the after show of Survivor: Australian Outback, Bryant Gumbel questions Amber Brkich and Elisabeth Filarski’s decision to wear bikinis that cover (slightly) more of their bodies than predecessor Colleen Haskell did. Both Amber and Elisabeth say that yes, they did choose to do that because they saw the way Colleen was captured and hoped to change it, if only a bit. Unsurprisingly, it didn’t really work, and the show kept filming women this way, and in the thirteenth season the producers chose Parv as one of the bodies they wanted to linger on with no regard for her mind.

In Parv’s second appearance, in the show’s sixteenth season Survivor: Micronesia, the gimmick is that a tribe of the show’s fans will be competing against a tribe of favourites. Allegedly, Parvati was not included in the collection of favourites initially, only being given an offer to appear on the season after fellow Cook Islands participant Candice Woodcock declined. As the tribe of favourites is introduced one by one in front of the fans in the premiere episode, Parv gets almost no response when she walks out, leading her to turn to Jeff Probst and sarcastically say, “Thank you, Jeff.”

The show’s alleged preference of Candice over Parvati is indicative of how the show views women. Candice is maybe one of the most boring, uninteresting contestants in the history of Survivor, but since she looks like somebody who could compete in a Miss America pageant and isn’t aggressively annoying, Survivor views her as a favourite. Candice never shows a real strategy, and the strategy she does choose is so weak that she doesn’t make it far after the merge. When she did return for Survivor: Heroes vs. Villains, Candice’s performance is similarly uninspiring. But she is a woman who falls in line and chooses the path of least resistance, so Survivor loves her. Parv is viewed as less of a favourite because her style of gameplay was viewed as one-dimensional in Cook Islands, again though only because of a combination of luck and the show’s edit of her.

Is Parv open about her strategy? Yes. She says that she is trying to flirt her way to a certain point, and in Survivors: Heroes vs Villains the way she rolls down her already very small bikini to make it even smaller can only be a further strategic move to help her continue to be underestimated. In Survivor, being flirtatious only gets you so far, and Parv knows this. At some point, you have to be able to operate as an individual to win Survivor, and Parv is more than capable of doing so if the necessary elements break right.

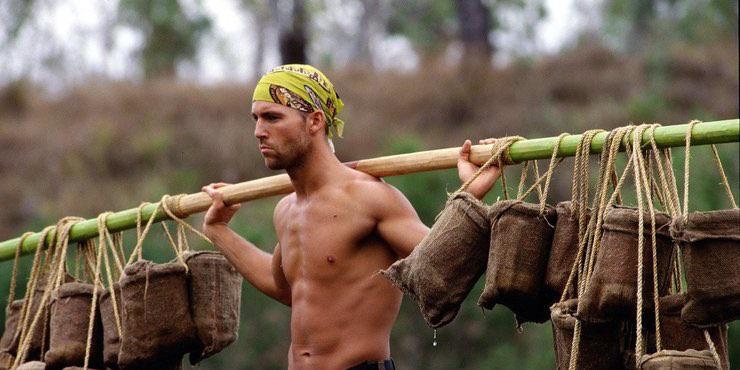

In Micronesia, Parv once again begins her alliance by flirting with James Clement, and the two team up to form an alliance with Amanda Kimmel and Ozzy Lusth. This carries them to the merge, where Parv initiates the blindside of presumptive finalist Ozzy almost immediately, beginning a run of four consecutive blindsides.

- Ozzy Lusth: the de facto leader of the merged tribe, holding a hidden immunity idol (that everybody on the tribe knows he holds) and the biggest immunity challenge threat in the history of Survivor in his peak physical condition, believes he has control over the alliance, and that Jason will be going home. Parvati Shallow leads the Black Widow alliance to vote for Ozzy, without telling her friends Amanda Kimmel and James Clement. Ozzy does not play the idol, and is visibly stunned and hurt when he is voted out.

- Jason Siska: After being sent to Exile Island by Natalie, Jason finds the hidden immunity idol that is replaced once Ozzy gets eliminated. Natalie then convinces Jason that James will be voted out at the next tribal council, even though Natalie knows the whole alliance is aiming at Jason. Again, the person with the hidden immunity idol doesn’t play it, and again they are voted out.

- Alexis Jones: Amanda volunteers to be sent to Exile Island, with reward challenge winner Alexis choosing her to go. Amanda uses the clues to discover that the new hidden immunity idol is buried under the tribe’s flag back at camp. Returning from Exile, she allows her tribe mates to search her belongings so they know she doesn’t have it, before enlisting Parv to help her distract others while digging under the flag. Parv succeeds, Amanda finds the idol, and when every vote gets directed Amanda’s way, Amanda plays the idol and her and Parv vote out Alexis. It’s rad.

- Erik Reichenbach: This one is painful to watch. Natalie convinces Erik to give up his individual immunity to protect her, and he is immediately voted out as the jury openly laughs at him from the side.

Parv is not the central figure in all of these blindsides, but she is prominently involved in each of them, and she knocks over the first, most important domino. The Black Widow alliance is a group of five women that becomes four once Amanda and Parv turn on Alexis, and eventually three for Parv, Cirie, and Amanda as was always Parv’s plan from day one in the Favourites tribe. When Amanda wins the final immunity challenge, she brings her friend Parv with her to the final two, viewing Cirie as a bigger threat to win.

At the final tribal council, Parv gives a great performance answering the jury’s questions, a skill Amanda simply does not have. Parv has shattered Ozzy too much to ever get his vote (he also confesses his love for Amanda at the same tribal council) and similarly insulted James, but it seems like she wins the votes of the people who are on the fence. Parvati is crowned the winner with a vote of 5-3, being rewarded for gameplay as opposed to Amanda’s focus on remaining likeable.

One thing that hasn’t been touched on here, and what helped her in this jury vote, is that Parv is a truly charming television personality. She is more engaging than most, possibly all of, Survivor’s contestants. When discussing her in Heroes vs. Villains, Coach says “She’s got the charm, she’s got the smile, and for some reason when she pays attention to you, you feel like you light up. It’s not that people don’t see it, it’s just that they are allured by her charm. And they’re taken by it. They’re smitten by it. It’s unbelievable.”

Randy Bailey says something similar in an interview, saying that “Survivor in so many ways is like the real world. You don’t get ahead by being smart, clever, hard-working. You get ahead unfortunately with a pretty smile and being able to schmooze people. And Parvati is the queen.”

In Survivor: Heroes vs. Villains, Parv aligns with Russell Hantz on day one. As opposed to the other contestants, nobody has any information about how Russell will play the game as his previous season hadn’t aired when production on Heroes vs. Villains begins. Opposed to the other alliances formed in this season, Parv is flying blind. But the people around her are also somehow still flying blind to her own skills.

Later in the season, JT gives Russell the hidden immunity idol he found, as a way to build trust and form an alliance with Russell, who seems to be controlling (and definitely believes he is controlling) the game. At the first individual immunity challenge, Parv and another player she is in an alliance with, Danielle, are the last two standing in an endurance contest. Parv steps down voluntarily, knowing Danielle needs to win to stay alive. Russell believes Parv is in trouble, so he gives his hidden immunity idol to Parvati to protect her (and protect Russell’s own alliance), totally unaware that Parv has found a hidden immunity idol of her own.

Even though Parv is told by Amanda, a member of the Heroes alliance, that the Heroes are going to vote her out, Parvati believes a lie is afoot. At tribal council, the Heroes direct their votes at Jerri, but Parv plays both immunity idols to protect Jerri Manthey and Sandra Diaz-Twine while making the gamble of leaving herself exposed. Russell is visibly surprised that Parv both has a second idol, and isn’t playing either for herself.

Parv guesses right, and nullifies the Heroes votes, sending JT home. As he realizes he’s going home, JT shakes Russell’s hand, believing Russell to have been the mastermind of his elimination. Incorrect. Parv manipulated Russell into giving her an idol, she found one of her own, she (by being good enough in the challenge to be one of the final two standing) allowed Danielle to win immunity, and then gave immunity to two other tribe mates to strengthen her alliance. It’s a truly epic Survivor move, and it is indicative of Parv’s mis-categorization that JT shakes the wrong person’s hand on his way out the door. Parv ends up being the runner-up in this season, losing to the person who became the first two-time winner of Survivor, Sandra Diaz-Twine.

Even though Sandra has an additional win on Parvati, I believe Parv is the greatest Survivor player of all time. Her skills in challenges are underrated, she is cunning, and she is able to adapt to the new gimmicks Survivor throws at her. Sandra should be considered the runner-up as greatest player ever, but the combination of Parv’s adaptability to new gimmicks, manipulation as the game changes around her, and physicality (as the game has gotten more physical with time) make her a true threat in any era of Survivor’s history, be it the past, present, or future. When Sandra and Parv are eliminated on the same episode of Winners at War, it’s worth noting that Sandra quits the game while Parv chooses to keep fighting from Extinction Island. Randy might have meant it derisively, but Parvati Shallow is indeed the queen.

At the beginning of Heroes vs. Villains, when the Heroes and Villains see who their opposition is after helicopters drop them on their beach, Jeff drops some interview questions that reflect the show’s further disrespect of the greatest player of all-time. As he is interviewing Tom Westman, and complimenting him on being a winner people rooted for, Jeff says “which isn’t always the case with some of our winners” as the image cuts to a shot of Parv. When Jeff asks if anybody on the beach believes they’re on the wrong tribe, multiple villains’ hands shoot up, and Parv speaks up.

“What did we do? What did we do that was so bad, Jeff?”

“Parvati, let’s be clear.” Jeff responds. “While you did a great job and were awarded with a million dollars, you lead one of the most notorious tribe of women ever in the history of the game. You betrayed people left and right. You guys were responsible for many, many blindsides. Great player? Yes, that’s why you’re here. Hero? No.”

Jeff asks the muscular James, who was betrayed by Parv in Micronesia, if Parv is a hero or villain. James, naturally, chooses the latter. Jeff says “James is bigger than me, James is right.”

Parvati’s response? “I will fight him… I’m not scared of him. I don’t care how big you are.”

You can throw whatever gimmicks, challenges, villains, heroes, idols, judgment, misclassification, and institutional sexism you want at Parvati Shallow. She will use it all against you, seemingly without your knowledge. No matter what, she will fight back.

Probstian Smarminess

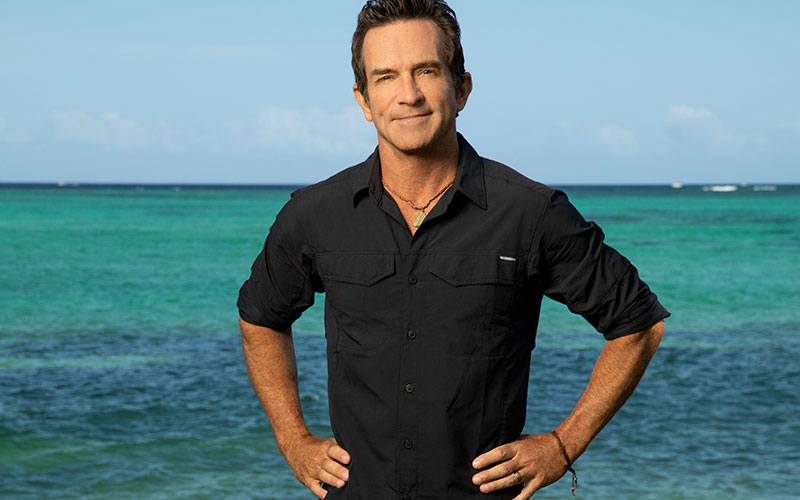

Survivor is hosted by Jeff Probst, who is good at his job. When the Emmy for Outstanding Host for a Reality or Competition Program was created, Probst won each of its first four years. (He hasn’t been nominated since his last win in 2011, not that he was undeserving.)

There are many things that make Probst good at his job: he is funny when he needs to be, engaging when he needs to deliver the drier rules and explanations involved in Survivor, and because he is good at prying information and confessions out of contestants at Tribal Council. He also looks like somebody who could be good at playing Survivor, which for some reason strikes me as a positive.

One can criticize Probst for many things, most of which are criticisms of the show itself. He often falls into an old school sort of sexism; he often doesn’t seem to realize (again, this goes for the show as well) when he’s counting out women or talking about their physical abilities (or lack thereof) too much. There are moments where he has acted in a way I would describe as repulsive, specifically in handling the moment when Sue Hawk quit All-Stars. Probst missed what Richard Hatch did to her in the previous day’s challenge, and when Hawk was emotionally breaking down and decided to leave the show, Probst was combative instead of supportive.

Perhaps most impressively, in Game Changers, there’s a truly shocking moment where Jeff Varner outs Zeke Smith as transgender at a tribal council, with Varner’s implication being that since he hasn’t told other tribemates Zeke should be seen as deceptive. Debates about whether or not this should have been broadcast at all are valid, and I have no objection to those who think it shouldn’t have been but, as aired, it’s a pretty remarkable conversation that Probst navigates deftly. Given his past history I never would have anticipated Probst would manage this well, let alone manage it well as it happened.

More recently, Probst has stepped up his skills when dealing with situations that are not easy to deal with. The mishandling of season 39 notwithstanding, Probst’s skills have grown. In a Winners at War tribal, when Sarah Lacina gave a speech about feeling discounted as a Survivor winner for being a woman, Probst admirably called himself out on his treatment of women throughout the twenty years he has held the job. Coming on the heels of seasons 39 I’m sure Probst was looking for a way to do this anyway, and elements of it do feel forced, but handling the moment well when it is given to you still deserves commendation. The show may not have really grown all that much in twenty years, but it’s good to see that at least Jeff can.

Survivor as a Comedy

Perhaps the most underrated aspect of the production of Survivor is its ability to make the viewers laugh. A big part of this, of course, happens in casting charming, funny contestants, but the show itself has to manufacture time for these personalities to shine through. In 39 days, with a collection of strangers, there are going to be moments of boredom that people fill with things that end up being funny, and it’s up to the show’s producers and editors to build these into funny segments.

In the first season, the cast often spends time looking for tapioca, which was planted around the camp before production. In Sue Hawk’s Wisconsin accent, the word “tapioca” is humorous, and when Sue Hawk is cut together saying “tapioca” eleven times in rapid succession, it’s even funnier. Survivor 40 has had a couple similar moments as well, with Sarah’s deadpan explanation of her career as a Survivor clothing designer followed by a brief fashion show at camp which she and Michele Fitzgerald performed humourously in. Earlier in the season, possibly the funniest thing I have ever seen on Survivor happened, as the editors pieced together instances of Nick Wilson walking into conversations with a dead-eyed stare, all of which happened during a pre-tribal council period of paranoia.

In Survivor: Redemption Island, Phillip Sheppard’s credentials as a former federal agent were questioned every time his name key appeared on screen, as he was credited as “Former Federal Agent?” question mark and all. In that same season, as David Murphy details Boston Rob’s control over the game at the final tribal council, the producers add a piece of music that is clearly meant to evoke the feeling of a Survivor equivalent to the theme from The Godfather. It’s hilarious.

The Stacey Stillman Story

In Survivor: Borneo, there was a contestant named Stacey Stillman on the Tagi tribe, and she was the third person voted out in the game. After the season ended, Stillman filed a lawsuit against CBS, alleging that Mark Burnett had engineered her exit out of fears that the vote would otherwise go against the 72-year-old Rudy Boesch (who, after the elimination of Sonja Christopher and BB Andersen, was the only contestant remaining who was over the age of 40). Stillman alleged that Burnett spoke to her tribemates Sean Kenniff and Dirk Been to steer their votes away from Rudy. Been would later testify in support of Stillman, and the case was settled out of court. Should you be interested in the whole rundown, Ianic Roy Richard wrote this comprehensive breakdown back in 2017.

Do I believe Burnett would have done this? Of course. A reality program is constantly being manipulated by its producers, and it’s not hard to imagine Burnett being fearful that his new show was eliminating all the members of a particular age demographic in its early episodes. I believe Stacey Stillman, and I hope she was paid well by CBS for exposing this. It seems likely that Burnett could have done this again throughout the show, and the Stillman case simply lead CBS to write even more detailed non-disclosure agreements for its future casts to sign. I choose to believe the producers tend to hang in the background post-Borneo, influencing the outcome more by selecting which challenges to use depending on the remaining contestants, but logically I know better.

In 2011, Survivor: Redemption Island introduced its first Edge of Extinction-style location, where eliminated players would have an opportunity to get back in the game. After one person is eliminated, they are sent to Redemption Island, where they await the next eliminated player. Upon the second player’s arrival, there is what Survivor calls a “duel” but is essentially like any other individual immunity challenge. The winner of that duel gets to stay on Redemption Island with the chance to return to the main game, and the loser is officially eliminated from the game.

The two tribes were made up of all new faces, with one returning player on each tribe: Russell Hantz and Boston Rob. Watching this season, it’s pretty hard to ignore a sneaking suspicion that it is being rigged by the producers to ensure that Boston Rob is finally able to win Survivor. (According to Richard Hatch, it was Hatch who was supposed to have Boston Rob’s spot.) As one of the game’s best players, and likely its most famous player, it’s not hard to see the show wanting to make sure their icon would go down a winner of the game. So, they engineer a gimmick that brings back two past non-winners, one of whom is charismatic and generally well-liked and skilled in Boston Rob, and the other is the infamous villain Russell Hantz. Whichever tribe Russell is on would immediately be fearful of him because they have seen him play a sociopathic game in two recent, consecutive seasons, and know he cannot be trusted at all. Unsurprisingly, Russell is voted out almost immediately, and loses his duel, causing him to be eliminated.

The rest of the cast is stacked with duds of contestants: on day one it’s clear that this is Boston Rob’s game to win, as long as he makes a few right decisions. “But what if he’s eliminated?” the producers asked themselves. Well, few are better at individual challenges than Boston Rob, so if he gets sent to Redemption Island the odds are still in his favour.

Boston Rob gets eliminated, dominates on Redemption Island, gets back in the game, and wins the million dollars.

Do I believe Survivor is always rigged by its producers? No. Do I believe Survivor has been rigged by its producers on multiple occasions? To think otherwise would be foolish.

The Ballad of Colby Donaldson

In the Australia-set second season of Survivor, Colby Donaldson is the runner-up. For years, he was considered one of the best contestants in Survivor history for his dominance in challenges, strong alliance with Tina Wesson, being charismatic in his confessionals, and looking like goddamn Captain America. One of the more fascinating facts* in Survivor’s history is that, in the year 2000 (the year of Survivor: Borneo), there were 1464 babies born named Colby. In 2001 (the year of Survivor: Australian Outback), that number jumped up to 3859.

*This information comes from the source of the Baby Name Institute, which is legitimately difficult to find information about as an institution today. So, take it with a grain of salt.

In an early season two confessional, Colby delivers one of the most comical lines in the show’s history. Explaining that he brought a giant Texas flag as his luxury item to use as a makeshift tarp for the camp (which is a very smart move), Colby follows his explanation with “But don’t get me wrong. When I wake up in the morning, I’m thankful for two things. I’m thankful I’m alive and I’m thankful I’m a Texan.”

At the beginning, the show tries its damnedest to sell the idea that there might be some sort of relationship forming between Colby and Jerri Manthey, but after a very small amount of time together it becomes clear Colby actively dislikes Jerri. He does, however, take a liking to Tina, and they work together to eliminate all their real competition (Elisabeth Filarski and Rodger Bingham particularly, both of whom would have been significant threats in a jury vote) until the final three is whittled down to them and the deeply unlikable Keith.

Unsurprisingly, Colby wins the final immunity challenge, meaning he gets to choose his partner in the final two. Somewhat surprisingly, he brings Tina. He would rather see himself lose than even give Keith a chance at winning. For the remaining duration of the final two format*, this decision is one of a kind. Tina eventually wins the final vote 4-3, and Colby leaps out of his seat in excitement for her. When questioned about his decision, Colby remains steadfast: he has no regrets, and would do it again. For a long time, I didn’t believe him.

*Survivor moved to a final three format in season 13, only periodically returning to a final two. This is because a final two scenario gives the winner of the final immunity challenge so much power – they essentially get to select who they would prefer to face in a jury vote. Had Colby taken Keith with him to the final two and won in a landslide, I suspect the show would have moved to a three finalist format earlier.

Colby makes two return appearances in Survivor: in All-Stars, where his elimination is arranged quickly by Lex van den Berghe as Colby is seen as a challenge threat, and in Heroes vs. Villains six years later, where he ends up in fifth place specifically because he is no longer seen as a physical threat. In Heroes vs. Villains, Colby’s performance in challenges isn’t impressive in the least, to the point where Jeff Probst actually questions him about it. This leads the famously competitive Colby to admit that maybe he just doesn’t have it anymore.

The most fascinating aspect of Colby’s run this season is that he doesn’t attempt to play the social game at all. He is on the Heroes tribe, with the literal white hat to prove it, and he forms a quick alliance with Candice Woodcock and Rupert Boneham, but beyond that he doesn’t do much. When his tribe loses an immunity challenge in episode six, Colby gathers the tribe when they return to camp and says he knows it’s his time to be voted out, and he’s at peace with it. He doesn’t want a day of scrambling and bickering, so he tells everybody to simply enjoy the day. That said, James Clement’s knee injury leads the tribe to vote for James instead, and Colby lives to fight another day.

Eventually, a bit of the old Colby flashes through, and he plays a key role in helping the Heroes tribe win challenges. After the merge, he even makes the winning shot in a shuffleboard-style reward challenge, sending him, Amanda Kimmel, and Danielle DiLorenzo to the home of Robert Louis Stevenson for a history lesson, meal, and screening of Treasure Island.

At this reward, Amanda is hellbent on finding a clue to the hidden immunity idol’s location, as she believes she will soon be voted out. However, Danielle finds it in a bowl of popcorn, and drops it next to the bed the three contestants were sharing while watching the film. Amanda gets up, grabs the note, which results in her and Danielle physically fighting over a tiny piece of paper while Colby remains hilariously unmoved on the bed, eating popcorn and watching a film. After an argument between Amanda and Danielle, they put it to Colby to decide, and he immediately says the note should be Danielle’s because she found it first. Amanda having the immunity idol would help Colby infinitely more than Danielle having it, and yet Colby knows who the clue belongs to.

This combined with Colby’s constant facial expressions, growls, and general grumpiness leads me to believe he’s the heir apparent to Rudy Boesch, and we simply couldn’t see it because physically they’re nothing alike. Colby is going to do what he says he’s going to do, and he believes in a steadfast right and wrong. There are no real examples of Colby being conniving; in the second season he doesn’t need to be because he’s almost always winning immunity, and in the twentieth he just happens to sneak by because he’s not seen as a true threat. But Colby remains himself. He is unchanged by Survivor. In the show’s history, there are not a lot of people as successful as Colby who do so without bending to the show’s whims and, even when given the opportunity to bend slightly in order to come out as the winner, Colby did not take it.

I now believe Colby would make the same decision if faced with the Tina/Keith choice again, and I believe Survivor as a game would be more interesting if it had more characters in its history like Colby Donaldson.

Heroes vs. Villains

Before Winners at War, the last time Survivor did a proper celebration of itself, it was in its twentieth season, commemorating the tenth anniversary of the show’s debut, with Survivor: Heroes vs. Villains splitting two tribes of return contestants into a tribe of heroes, and a tribe of villains. The moral grey area on Survivor exists no more, apparently, and the show begins to look at its contestants in a binary sort of way. Colby “Captain America” Donaldson and Jerri “the original black widow” Manthey even wear similar hats, with Colby’s white and Jerri’s being black, because of course.

Some of the divisions don’t make perfect sense, though, because Survivor as a game illustrates that you need to be a villain with heroic attributes, or vice-versa. Boston Rob is classified as a villain, even though he’s a hero to many of his former All-Stars who he protected through to the final five. Two of the Black Widow Alliance from Micronesia (Cirie and Amanda) are classified as heroes, while fellow Black Widow Parvati* is classified as a villain. But where the division matters comes in the butting heads of Russell Hantz and Rupert Boneham.

*Interestingly, in contrast to All-Stars when past winners were eliminated immediately, winners participating in Heroes vs. Villains are not viewed as threats. The final three for this season ends up featuring two previous winners.

Rupert, a veteran from Pearl Islands and All-Stars, views himself as a heroic figure and the show positions him in a similar fashion. His tie-dye tank tops and shaggy beard, combined with his tendency toward pontificating about honour turned him into a fan favourite, and his ability to remain true to himself seemed to keep him there.

Russell, on the other hand, was a tried and true villain. Coming right from the previous season of Samoa, Russell built his game on lying to everybody pretty much all the time, and never being able to see why people might view that as a problem. In short, Russell is an out and out sociopath. In Samoa he would burn people’s socks without their knowledge, and dump water out of canteens, and in Heroes vs. Villains he continued the act by burying his tribe’s machete.

The majority of Heroes vs. Villains is controlled by Russell and Parvati, each alternating periods of being the most threatening villain, as some post-merge in-fighting leads heroes like Colby and Rupert to stick around longer than they might have felt they could. Eventually, Rupert’s luck runs out, and Colby’s does soon after, leading to a final three of Russell, Parvati, and Sandra.

Going into the final jury vote, Russell seems convinced that he is going to win. Like in Samoa, he feels his other two competitors will be seen as coattail riders, and doesn’t see how they could be considered to get the jury votes needed to win. Watching this season from the outside, however, the opposite seems to be true: I couldn’t figure out how Russell was going to get a single vote. Parvati made the most aggressive move of the season, playing two idols (neither for herself) at one tribal council, maintaining the villains’ control of the numbers and eliminating JT. Sandra played a solid game as well, making moves when she needed to and consistently pushing herself as the underdog of the villain alliance. Russell, on the other hand, aggressively lied to everybody, swore on his children’s lives and didn’t keep his word, and in general was a deeply unlikable human being to be around even to members of his own alliance.

When faced with questions from the jury, Russell refused to backtrack on his actions, and did not even appear capable of grasping why people felt wronged by him. Meanwhile, Parvati and Sandra answer questions thoughtfully, as they explain their gameplay and do nothing but make themselves appear worthy of winning the jury vote. In retrospect, this jury vote is a competition between likely the two greatest Survivor of contestants of all time, and then also Russell Hantz.

To get to the final three, Russell had one key advantage going into the season, an advantage that is everything on Survivor. Given the compressed production timeline between seasons, Survivor’s nineteenth season (and Russell’s first appearance) hadn’t aired before the contestants on Heroes vs. Villains went off for the production of season twenty. All players knew about Russell was that producers told the contestants that Russell was one of the biggest villains in Survivor history. So Russell had seen the game tape on all his opponents, yet they hadn’t seen the tape on him. If this season had been played six months later, I have every confidence that Boston Rob would have engineered Russell’s demise very early in the game. But that’s not how it played out.

The jury vote came back with a decision of 6-3-0 in favour of Sandra, and Russell receiving no votes. As Jeff Probst reads the votes aloud, alternating a vote between Parv and Sandra, you can essentially view Russell melting down as he realizes he is not going to win. During the reunion show, Russell aggressively talks over Probst, trying to make his points as to why he should have won, and once again refusing to grasp any other person’s perspective on any given situation.

In the reunion show, Probst announces that there was a vote conducted, where the fans vote on their favourite player of the season. The two finalists are Rupert and Russell, and for the second season in a row, Russell wins this vote, collecting $100 000 for his successes. The jury of his peers might not like him, but those watching from afar can’t get enough.

At the Survivor: All-Stars reunion six years earlier, the first time a similar fan favourite award was given out, Rupert came out victorious, winning a controversial sum of $1 000 000. The difference between the votes Russell won and the vote Rupert won? About ten million viewers. The finale of All-Stars garnered almost 25 million viewers, while by 2010 the Survivor finale only brings in 13 million people (and Russell’s previous season was even less). It is in the period between All-Stars and Heroes vs. Villains where Survivor’s cultural imprint dwindles, both through the formula growing tired and the expansion of home entertainment options. When we all still watched, Rupert was the favourite. But the people who stuck around with Survivor tend to favour Russell.

]]>There are many ways to delude oneself, typically with no good reason to actually believe it. You can focus on your work in order to convince yourself you’re not lonely; you can hide in a movie theatre to avoid existence; you can stare into your phone until fiction becomes fact. None of these things ever work out exactly how you hoped though, because nothing ever does. You miss out on everything else: time, money, hope, all of which compounds into negatively affecting your own future. You could accept this loss early on and get on with it all, or you could let it quietly fester within you… Or you can just go to space instead. Your call.

Ad Astra is the latest film from James Gray and – as per all of his previous films – it is very good. After an introductory action sequence on a truly gigantic antenna, featuring our hero Roy McBride escaping a mysterious technological surge, Roy is informed that those surges exist all across the world. They appear to be caused by the remnants of the Lima Project, an exploration mission lead by Roy’s father Clifford who was assumed to be dead, leading a mission that was assumed to have failed. Roy soon launches into space to find his (until now) presumed dead father – a father who left him and his mother behind years ago – in order to continue his celestial search for extra-terrestrial life forms.

A lot of things happen in the interim, as the journey passes space pirates and recording booths and Natasha Lyonne, but the viewer can always safely surmise Roy is going to make it to Neptune to see pops. (The viewer has already seen early in the film that Roy’s father is played by Tommy Lee Jones, and that cantankerous curmudgeon doesn’t sign onto a movie merely to pose for a photo in a spacesuit.) This isn’t a movie about whether or not the hero gets from Point A to Point B, it’s moreso about the zigs and zags along that path. So, of course, Roy gets to Neptune and, of course, his father Clifford is still alive hacking away at his own interplanetary quest.

Upon entering his father’s ship, Roy talks to Cliff and – in an inspired writing choice – Cliff immediately tells his son that he didn’t miss him while he was gone. Despite leaving his son when Roy was 16, living a wholly solitary existence on Neptune for years, Cliff never thought about his son once. The look on Roy’s face as this information is relayed to him conveys to the audience that he knew this the whole time. Roy simply had to hear it from the wrinkly-eyed oracle himself before he could admit it out loud.

Brad Pitt’s performance as Roy has been appropriately ballyhooed, with most of its power contained in static frames of Roy’s face, merely processing information. Perhaps Pitt’s strongest moment in the film comes right as his father Clifford is telling him that, “Hey, I never thought of you once while I was gone. Kick rocks, kid.” When we watch Roy experience this, Pitt chooses to barely move. He sheds a tear, but other than that he is essentially motionless. And yet you can see him registering the most powerful emotion of the movie on his face: “I fucking knew it.” You watch a man break not because of what his father says to him, but because of what he already knew and refused to believe. Then, and only then, can he vocalize what he knew to be the truth all along: “I know, dad.”

You can get where you’re going, you can experience what you wanted to experience, but the only thing you’ll learn is that which you were afraid of the whole time.

Earlier today, I was bored. When I say bored, though, I mean what all of us mean when we say we’re bored in 2020: I had nothing immediately pressing to do, so I aimlessly looked at my phone while standing and waiting for my rice to cook. I did not stare off into space, as I would have ten years previous, and I did not get out my book to read due to the relatively short time I had to kill. So I scrolled. I found nothing, as I always do. And yet, I will do this again, presumably before I finish this writing session, despite the fact that I know it will break my focus in a way detrimental to the finished piece. But a Vanity Fair cover story on Joaquin Phoenix is peaking out at me from the browser tucked behind my word processor, and those meaningless photos aren’t going to scroll through themselves. He looks like he’s laughing on a couch! Must-see content!

We live a life of quietly agreeing to believe one technological snake charmer or another, about one snake oil or another. If something doesn’t fit what we’re looking for, we can rest easy knowing that we can keep looking, scrolling on by until the next thing fits our exceedingly temporary needs. The technology in our pocket has instructed us that we control everything, so if we find something we can’t control we can wall ourselves off to it until we find the next desirable thing that we can control; contrary thought need not apply, for it shall be swiftly ignored. And if we don’t find what we want, we continue our unending scroll, our search for what will satiate us in the precise way we wish to be satiated.

Do I think this world is broken? Yes. Do I believe it is unfixable? Honestly, kind of. I believe that, at some point in my lifetime, we got to a stage where everything was good enough. If we called off the search for all non-medical technological advances in 2007, we probably would have been okay. I would have been cool with stopping the day before the announcement of the first iPhone; the internet is an immensely powerful and wonderful tool, but maybe we don’t need it in our pocket at all times. (Admittedly, this point comes from a place of privilege: as somebody who has lead a comfortable, North American existence, I felt and feel we were far enough by 2007. I recognize technology has given voice to many members of the previously voiceless who actually need to be heard. In this piece, I suppose, the views on technology apply to me and people living existences similar to mine.)

People have been bitching about technological advances made in their lifetime since the dawn of time. Everybody misses how things used to be, even though “the way things used to be” is a relative experience. Cave painters would have probably complained about society’s introduction of the paintbrush had they lived long enough to see the day. In 1845, Henry David Thoreau famously eschewed society entirely, making his own world on Walden pond so he could focus on his writing. Over a century later, Ted Kaczinsky took a more aggressive, exploding-mail sort of approach towards eschewing society from a cabin in the woods. I am not going to retreat from society; I am too deeply entrenched (and I also kind of think Thoreau was a defeatist, let alone my thoughts on Kaczinsky’s repulsive actions). I’m going to stay here, and I’m going to worry that I made the wrong decisions on how to spend my time today, yesterday, and tomorrow, and I justify continuing to do this by saying everybody else around me is doing the same thing. As you can see, because you are reading this.

Now, my stance on modernity is (obviously) hypocritical. This website exists as the stepchild of a blog that was founded in 2009, after I had read enough opinions online to think mine were thoughtful enough to publish. Our podcast, where we recently discussed Ad Astra, exists because of the continued growth of what is now called content. I heard enough voices talking about movies, and I thought James and I could do better, in an at least semi-unique way. Did we succeed? I don’t know. But we tried, which means I have contributed to the surge (albeit a surge that strikes back quietly, and at a smaller scale, but constantly). Now I suppose I’m trying to figure out how to shield myself from its repercussions.

In Ad Astra, Roy puts on his helmet and blocks out the world. It’s present the first time we see him onscreen, and it’s present the first time he interacts with a human being. He keeps a shield between him and others (albeit often out of intergalactic necessity). Early in the film, working on the biggest satellite the world has ever seen, Roy crashes back to earth after the action scene that introduces us to the surge. His parachute ripped, he hit the ground hard, and then people came to pick him up. In this instance, Roy needs help. But as soon as those people enter his sightline, the scene blacks out. We don’t see any interaction between Roy and this crew of unknown people sent to help him out.

After this, as discussed above, Roy goes through a lot of shit. Interplanetary travel and whatnot, not to mention being told by his father that he is unloved. But the key thing of what Roy learned is explained to us in a voiceover about his father, a man whose glaucoma can no longer allow him to see very far in front of him. In a piece of voiceover, Roy breaks down all that Clifford found, all the beautiful nothingness of these planets. They looked gorgeous and were impressive discoveries, but there was nothing there other than surficial beauty. Clifford didn’t find the beings he knew and still believes are out there, which is why he wants to keep looking. Roy knows this is foolish – he has discovered that there is nothing to discover, and Roy can accept what Clifford can’t. As he says to his son, pleading to stay on the ship: “I have infinite work to do.” Roy knows now that, at some point, it’s time to give up. To revisit the hackiest moment in the film, sometimes you have to let go of something gnawing at you, as Clifford says to his son in the father’s final moments on screen.

After a bunch of survival excitement, Roy gets back to earth, his pod crash landing in what feels like a slightly more relaxed callback to his fall from the antenna earlier in the film. This time, however, Roy needs somebody to pull him out. His legs won’t work after living so much time in zero gravity, so if only out of necessity he needs to give himself over, and the scene doesn’t black out as soon as the rescue crew arrives. Roy raises his visor to reveal his comically well-groomed space travel beard, and he raises his hand. Somebody he has never met before grabs it, pulling him away from a technological advancement and into his own, uncertain future. The camera tracks down to reveal the seat of his craft, unoccupied yet still in focus, as Roy moves off into the blurry, unknown future all the while in the hands of others.

There’s a short epilogue after this, of course, a scene of Roy sitting alone in a café, sipping a lonesome latte as he awaits his long lost paramour Eve to come meet him. Now, there are a million reasons to not like this sequence, all of which hit me immediately. Below are a quick sample of said ideas:

- Ugh. We have been given no reason to believe Eve would go back to Roy.

- Okay well that last word choice was actually pretty strong.

- This doesn’t seem like an ending James Gray would write.

It turns out that, well, James Gray didn’t really want to write it. At the behest of the moneymen, Gray came to the compromise of adding a way-too-cute button to his otherwise wordless and eloquent ending. It’s a cinematic tale as old as time: formerly beautiful ending and the capitalistic beast. In discussing the conclusion of Ad Astra, both Gray and his star (who is also a producer on the film and therefore a part of these endless meetings and email chains), have been eloquent on the matter.

Brad Pitt, in the LA Times: “I don’t see it as a change, I see it as evolved. […] From the beginning when we started with the script, the basic structure was there, the architecture of ‘we’re going to go to the moon, then we’re going to go to Mars and then we’re going to go to Neptune.’ But so much of it has constantly been in flux, I don’t see that as change. I see that as a natural part of its growth.”

James Gray, in Dazed Digital: “That last 40 seconds was very much a collaboration and a compromise. […] But I was OK with it, because if the movie felt like a downer, I was going to get very upset. The point of the movie isn’t that he goes to Neptune, confronts his father, and then becomes a miserable guy. The degree to which that was clear to the audience, I was OK with it. And besides, my ending is in the movie (before those 40 seconds).”

As has been much discussed, Ad Astra is a grander movie than Gray has ever attempted to make before, both visually and financially. Depending on what figures you’re looking at – I am of the mind that any figure I can find is probably wrong, but at least indicative of scale – Ad Astra came in at a budget three to four times higher than The Lost City of Z, and in order to convince money people that their faith is properly placed, sometimes you have to make some concessions to get all the money you need to tell what is still (mostly) your story. There is both good and bad in this new Ad Astra ending. The aforementioned matcha meet-up is a stone cold screenwriting bummer, sure, but the return of the psychological testing that is intercut within at least adds a subtle tie back into the film’s beginning.

During the opening sequence, a collection of various introductory shards that explain to us where Roy is coming from, we hear Roy give a psychological test, which becomes a recurring event throughout the film as mandated by his profession. When we see Roy give this test at the beginning, he is calm of course, but the way he is framed is slightly obfuscated. The image doesn’t feel clear, like we’re being forced to look through some translucent glass to get to what Roy is saying.

In the final sequence, after Roy has returned, we can see him give his psychological test more clearly. The image is as crisp as can be. The only other noticeable visual difference comes in the helmets we can see reflected in glass around Roy, helmets Roy no longer needs. He is giving himself over to the world in front of his face, removing the shield that he has kept in between him and it for so long, so that he can live his own life. He has learned that the way to shield yourself is not to wall himself off; Roy can make a kingdom for himself that way, but it is a false kingdom. It’s a dictatorship run by somebody who can’t see more than six inches in front of his face. Anything you think you have perfected within it is a lie.

Speaking to Bilge Ebiri in Vulture, James Gray discussed the paradox of an unending quest, through the lens of filmmaking.

“One time, if I may drop his name, I had this fantastic conversation with Martin Scorsese, and he was talking about La Strada and he said, ‘I wish I could make a movie like that.’ I’m like, ‘You’ve made incredible movies, maestro.’ And he said, ‘I never made anything like that.’ I think the tragedy of Tommy Lee’s character is that he never found a pleasure in the beauties that he discovered. He never found beauty in the idea that human beings are what matter. The idea of striving is what matters.”

You can’t control everything at any level of filmmaking, at any level of existence, and to make any film you need to be honest with yourself about that, let alone one that costs as much as Ad Astra. The grander the vision, the more likely your vision will be messed with, but it’s better to try and fail and take the learning that comes with that than to stay hidden, meddling but protected in obscurity forever. You can have an infinite amount of work to do, reaching for something just ahead that isn’t really there, continually making changes because you feel you can’t get it right. At some point, you must accept that you have done as well as you can and learn to live within the world that is available to you. Submit.

]]>

Alex writes a year in review of 2019 of sorts, and an appreciation of Little Women.

For as long as I have been conscious of these things, 1999 has been a “great movie year.” Various online content factories spent all of 2019 reminding us of that fact and, for once, their impulse was not idiotic.

By the end of 2007, I was extremely confident that it too was a similarly great movie year. At the age of 21, I was aware enough to know that the ability to see Michael Clayton, There Will Be Blood and No Country for Old Men within a couple of weeks of each other meant there was something happening in the Hollywood water, metaphorical water that I aggressively guzzled as frequently as possible.

I felt a similar sensation at the cinema as 2019 began to draw to a close. Despite a fairly bleak desert of cinematic options for the middle third of the year, the winter swooped in with movie after movie that I deeply enjoyed, in a way that reminded me of what was happening toward the end of 2007.

Why does this matter? How does whether or not a collection of great movies get released in the same year affect anything? If Dreamworks hadn’t been pre-occupied with Saving Private Ryan’s 1998 awards campaign, does American Beauty get produced as fast as it did in 1999? If there had been an unexpected monsoon in the Texas desert, delaying No Country for Old Men and There Will Be Blood’s neighbouring productions (and releases) a few months, would that have swung my opinion on 2007? What if Disney shelves Ford v Ferrari as a relic of the old, pre-merger 20th Century Fox? Does that affect 2019’s standing? And does it actually matter? I truly don’t know.

One thing I am fully confident on, however, is that this essay is going to end up as being much too close to something I wrote but a month ago, a piece that by its conclusion had comfortably stated my suspicion that 2019 will be remembered as a good year. So be it. When I wrote that one, I hadn’t seen Little Women yet, so now I’ve got some new things to say.

Admittedly, Little Women was not a movie I anticipated loving. Greta Gerwig has been on the Chris Pratt No Bueno list since I wanted to rip my eyes out in the middle of the interminable Frances Ha. I liked her solo directorial debut Lady Bird, albeit nowhere near as much as the rest of the moviegoing public seemed to. (Like so many other films, I saw why people loved it, it simply didn’t connect with me the way it did with others. This is fine. These things happen.) As a sporadically logical person, I tend to view my previous reactions to an artist’s work as potentially indicative about how I will feel about their next piece and, as such, expectations were measured. In this case, as in so many others, my assumptions were incorrect.

Early on in Little Women, I was pleased if not excited. I had suspected there could be some modernizing by way of time-shifting in this film, and lo and behold there was, pretty much immediately. We’re introduced to Jo as a writer in New York, before flashing back to her home life as a younger girl. As the scenes set in the past began, I noticed a certain vibrance to everything. It all felt a little too warm: the performances, the faster pace of the Christmas morning dialogue between the sisters, even the hue of the shots themselves looked warmer than the previous scenes. Sunlight and fireplaces had replaced overcast skies and wet city streets.

“Anyhoops,” I thought, “this could be interesting, should it turn out that they’re being directed totally differently for a turn to come later or something… But that surely won’t happen.”

In the early 1990s, Hollywood was coming out of the initial post-Jaws, post-Star Wars boom of diving full-on into the world of embracing stories specifically designed to please the highest number of people possible. The idea for so long – buoyed by the success of Steven Spielberg’s work both as director and producer – had become to make a film that couldn’t possibly offend anybody in order to maximize its box office opportunities.

Throughout the 1980s, there was an independent movement bubbling in American cinema, with the burgeoning success of Michael Moore, Spike Lee, Jim Jarmusch, Gus van Sant, Richard Linklater, and the Coen Brothers coming all relatively close together, followed by Steven Soderbergh winning the 1989 Palme D’Or at Cannes for Sex, Lies & Videotape. These were all filmmakers inspired by the mainstream in some capacity, but willing to look a bit left of centre to tell the stories in a slightly different way, which culminated in the success of the wunderkind who came slightly after them, Quentin Tarantino. After Reservoir Dogs was a Sundance success, and Pulp Fiction became a cultural sensation, all the studios were looking for their own burgeoning young auteur. This is how Paul Thomas Anderson, David O. Russell, David Fincher, Spike Jonze (plus Charlie Kaufman), Alexander Payne, Christopher Nolan, et. al became enmeshed as a sort of Hollywood New Wave, the biggest wave of talent to hit Hollywood in a limited time period since the famed 1970s*.

*This is all incredibly simplistic analysis of this period, and the periods leading into it. I know this, and therefore it is lacking certain context. But providing that would take longer than you’re willing to read here. To get a fuller picture of the story, I recommend Peter Biskind’s exceptional Down and Dirty Pictures or Sharon Waxman’s compulsively readable Rebels on the Backlot.

In his 1999 book Getting Away With It, Steven Soderbergh poses fellow director Richard Lester a question about infamous genius Billy Wilder, and how Wilder’s almost incomparable run of quality finally came to an end in the 1960s.

Soderbergh: We’ve talked about sustaining, and I’ve always thought Billy Wilder is an interesting case. Clearly around the late sixties his view of society or his take on society became… well, not interesting to an audience.

Lester: He had a very oblique take on a very formal structure, and then that structure was taken away and there was an empty field there and he didn’t have to become oblique.

What they’re discussing is the way Wilder’s greatest successes played with the form developed within the studio system, allowing Wilder to offer his take on various genres, all with a Wilder twist. As the 1960s became more aggressively experimental throughout cinema, Lester is arguing that – despite being debatably the most versatile director who ever lived – Wilder lost his way of connecting with the masses, because his formal experimentations stood out less as cinema as a whole got more experimental.

Jump forward to the 1980s and, as the new establishments of the 1970s and 1980s are being cast in cinematic amber, the auteurs of the 1990s came along to play with whatever toys were left strewn about, building to the formal experimentation cresting in 1999.

Ten days after the Oscars where 1998’s Shakespeare in Love was crowned Best Picture, The Matrix hit cinemas and a year later American Beauty won Best Picture. Despite not necessarily being my choices for the two best films of their year, it’s helpful to look at American Beauty and The Matrix as indicative of 1999: the big, commercial success (that was also critically successful) and the critical bellwether (that also made oodles of money).

American Beauty and The Matrix both had something the audience was ready for – suburban discontent, and sci-fi extravaganza, respectively – but something that they had been prepared for even without their knowledge, by films like Blue Velvet and Star Wars. But what these 1999 films did was twist what we expected ever so slightly: right off the bat, Lester Burnham told us he was already dead, and The Matrix asked if we were ever really alive. (These are small things, sure, but this was the year of Blink 182’s All the Small Things.)

The cinematic earth rumbled in 1994 when Tarantino made a pop culture-infused crime movie, but it was only able to become a sensation because it didn’t throw too many things out of whack. These 1999 movies all posed questions that seemed new, with structural deviations throughout, but they all came back to ideas we had already accepted in other previous films. The cream of the 1999 crop boiled down to family drama (Magnolia), teen films (Election, 10 Things I Hate About You), war movies (Three Kings), revenge thrillers (The Limey), office comedy (Office Space), and whatever you classify Being John Malkovich as. And since most of those films didn’t do particularly well at the box office, the successes of The Matrix and American Beauty were what people wanted to imitate.

After American Beauty’s (and Shakespeare in Love’s) success, and the sporadic success of some of these other meteoric auteurs, major studios began developing boutique distribution wings, in order to find their equivalent to Miramax to help bring home a Best Picture statue. The early to mid 2000s were rife with films (presumably) pushed into production by the developments of the late 1990s, with films like Little Miss Sunshine, Sideways, Lost in Translation, Almost Famous, Finding Neverland, and infamous Best Picture winner Crash combining different aspects of American Beauty and/or Shakespeare in Love’s success, to varying degrees of success. Miramax had been the little engine that could (win Best Picture), and then Dreamworks proved you could do the same thing even faster. Crash’s Best Picture win a few years later similarly minted Lionsgate and Bob Yari Productions (although the latter declared bankruptcy before the decade was out). From an outsider’s perspective, it seemed the success of some of these films gave studios, the majors and their minor boutique wings, freedom to be creative, freedom to listen to an idea they might not immediately have bought in the past.

“Maybe it’s the next American Beauty,” they surely said about whichever genre/tonal hybrid came across their desk.

Smash cut to 2007, and you have a group of movies made by filmmakers at the top of their game, but still films that could be palatably explained to people wearing suits. It was a collection of miscreants, but miscreants that could be described in a very sellable sort of way. See below for proof.

ZODIAC

What it really is: a movie about journalism, the internet, and how having more information at your fingertips doesn’t necessarily make the world make more sense.

What it could be described as: The director of Seven returns to the world of serial killers!

THE ASSASSINATION OF JESSE JAMES BY THE COWARD ROBERT FORD

What it really is: a Terrence Malick-inspired biopic about how fame destroys these men, both famous and otherwise.

What it could be described as: Brad Pitt in a Western about the most famous American cowboy of all time!

GONE BABY GONE

What it really is: a kidnapping thriller that features some surprisingly spot-on media criticism, directed by a man who had very recently been a heavy focus of the media.

What it could be described as: a kidnapping thriller in Boston! Remember The Departed?!?! You love Boston! Funny accents!

MICHAEL CLAYTON

What it really is: watching a man and woman dissolve underneath the weight of the moral implications of their corporation-driven legal jobs, and the effect it has on each of them.

What it could be described as: George Clooney fights the system in a legal thriller!