Alex writes about the way Jay Z’s new album has been reviewed, as well as a variety of other topics.

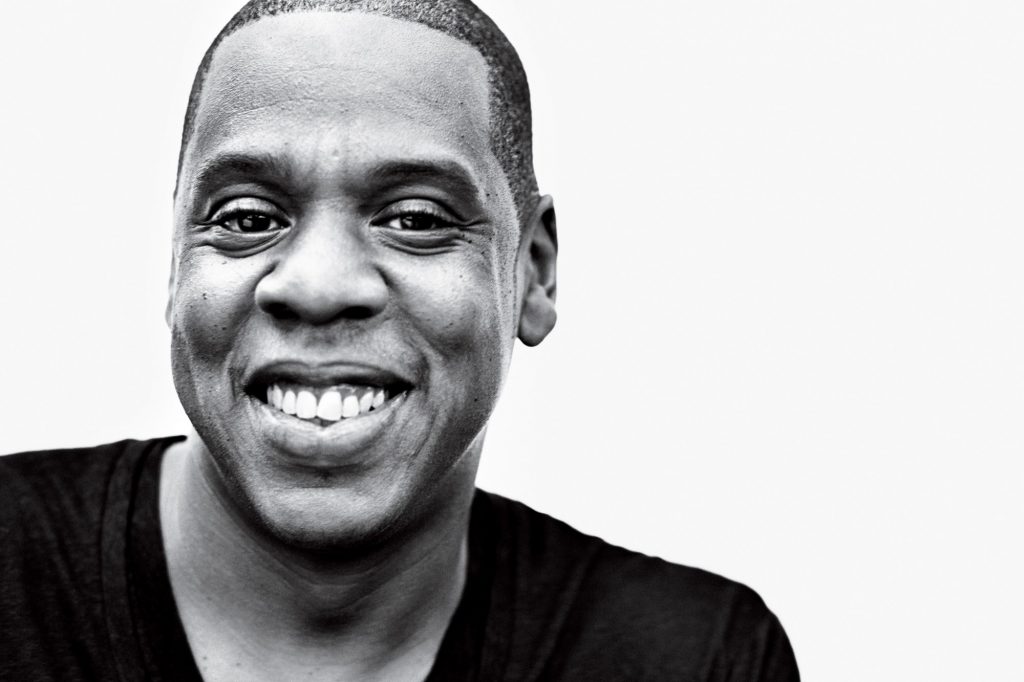

By the time I heard Jay Z’s 4:44 for the first time, it had gone through the first wave of instant criticism and commentary, as will happen now when an iconic talent releases a record at midnight on a Friday. There were the GIFs that told me Hova confessed to cheating on his wife, there were idiotic reaction videos of idiotic people making idiotic faces during a couple lines of The Story of OJ, and critics rapturously declared this an important album (even more so than a traditional Jay Z album would be). This is the modern popular music climate now: to a certain kind of person, it can be exhausting before you even hear the music. As such, everything becomes divisive, and I eventually declared 4:44 a bit boring when I finally got a chance to give it a listen two days later.

Parts of 4:44 simply sounded like Jay Z’s much ballyhooed flows were a tad lazy, lacking a certain crispness. Like much of his previous record Magna Carta Holy Grail, the ratio of Jay Z cranking dingers in a game and half-assing it in batting practice seemed to be out of whack. There were things about 4:44 I loved instantly – The Story of OJ is a truly fantastic song that stands among Jay Z’s finest work – but by the halfway mark I was starting to realize I wouldn’t end up feeling the way most were about this album. I enjoyed the ideas behind the songs, and while it picked up toward the end, there was too much to dislike.

That said, even when discussing a Jay Z album I don’t love, there’s always much to like. There is nobody in hip-hop better at crafting single lines that you only have to hear once to get them forever lodged into your brain. (A couple of 4:44’s best include the DUMBO section of OJ, and the line “Shout out to all the murderers turned murals” on Marcy Me.) His ability to pick only the most expensive, lush beats is well-documented, and producer No ID was up to the task here. Even the overly positive critical reaction warmed my heart a little, as this was the first hip-hop album that could be added into a critical category best exemplified by Bob Dylan’s Modern Times.

In 2006, Bob Dylan released an album that was rapturously received by critics despite smart people observing it as “kind of okay.” The reception was so overwhelmingly favourable that even critics writing positive reviews still felt like they had to comment on it. In his review for The Guardian, Alexis Petridis writes that, “It’s hard to hear Modern Times’ music over the inevitable standing ovation and the thuds of middle-aged critics swooning in awe.” (This was a sentence that came in the middle of a four-star review.) A legacy artist simply has different goal posts to hit; when you release Highway 61 Revisited in your twenties, you only have to kick twenty-yard field goals in your sixties to make people think you’re Stephen Gostkowski. These things happen all the time – it happened with Bruce Springsteen’s The Rising, depending on who you ask it may have just happened with Martin Scorsese’s Silence, and if Eminem’s next album is a stripped down confessional record without any use of his favourite homophobic slur it will happen for Marshall, too. But Jay Z made it happen first for hip-hop, because that is Jay Z’s place in the world of uber-popular rap music.

After the very good American Gangster’s release in 2007, Jay’s two subsequent solo albums Blueprint 3 and Magna Carta Holy Grail, were a bit lacklustre*. So when he released something kind of good a couple weeks ago, critics went kind of nuts over it – as they had for Dylan eleven years ago – as though somebody they had all anointed a hero had returned to his best form after a period of mild dormancy. The truth is, he hadn’t really returned. Sometimes one’s best days are simply behind them.

*It must be noted that Watch The Throne came out in the middle of these two albums, and that Watch The Throne is mostly fantastic. Admittedly, most people seem to look at that one more as a Kanye West album Jay Z was featured on a lot though.

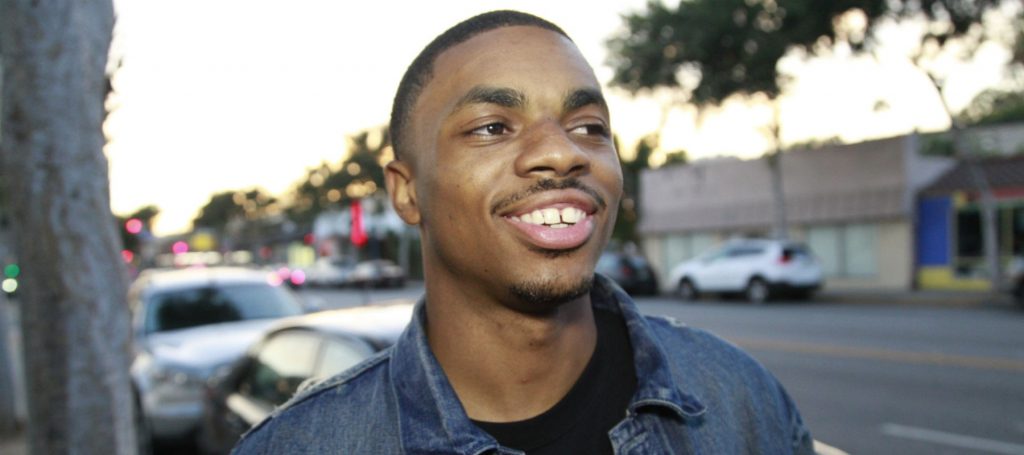

A few days before I listened to 4:44, I listened to Vince Staples’ new record Big Fish Theory, an album that I loved immediately. Staples somehow made an album that feels similar and entirely different from his previous full-length, Summertime ’06, an adventurous album filled with uncommonly honest lyrics and uncommonly inventive beats. Critics have strongly supported Big Fish Theory as well, as Vince Staples is somebody people such as myself feel a strong inclination to support – he is an artist who is doing things as we have always wanted them to be done, albeit with a slight twist.

This time, that twist was throwing in some elements of dance music, which came together more or less flawlessly within Staples’ pre-established use of unorthodox sounds. Most critics went a bit overboard in talking about such modern soundscapes; Big Fish Theory feels more adventurous than it is simply because it begins with Crabs in a Bucket, easily the most dance-oriented song on the album. But outside of a conversation of its avant-garde bona fides, Big Fish Theory is a fantastic rap album with at least five songs* I can imagine myself listening to regularly for years to come (just like I have with Jump Off the Roof, Summertime, Lift Me Up, Like It Is, and pretty much everything else on his previous album not titled Senorita). My concern is that I’m only able to feel this way simply because the mass conversation has passed Staples over; his music is less divisive than Jay Z’s simply because more people feel a need to weigh in on something that crosses all quadrants, something that reaches all of our timelines. Vince Staples is not as far to the left as some critics claim, but he’s certainly less central than Sean Carter, and people only get mad about art that everybody is talking about.

*Big Fish, BagBak, Yeah Right, 745, and pretty much everything on the album not titled Love Can Be.

A couple of months ago, Trey Parker and Matt Stone were on the Bill Simmons Podcast, during which Stone got charmingly riled up over a couple of movie reviews in the New York Times, reviews that fuelled the themes and storylines of the most recent season of South Park. While conceding that, “This is the dumbest, smallest thing to get mad about in the whole world,” Stone continued to discuss how positive reviews for Star Wars: The Force Awakens and Ghostbusters lead to how they treated Trump and Clinton through the season. While conceding that The Force Awakens is a blandly good movie, Stone says that it’s not the type of movie that is supposed to get a good review in the most vaunted of media outlets*. Manhola Dargis’ polite references to the movie hitting all quadrants while being repetitively enjoyable irked Stone deeply, because he feels film should be treated more seriously, or at least feels the most visible critics should be holding film to a higher standard. Admittedly, I’m filling in the blanks a bit here, but that sort of legwork isn’t needed when talking about Dargis’ semi-famous, ultra-positive review of Ghostbusters titled, “Girls Rule. Women Are Funny. Get Over It**.” Neither Stone nor I disagree with the statements in the title, but the attachment of it to a movie that did not rule and was not funny made it hard to get over.

*It should be noted that Vincent Canby’s original NYT review for A New Hope was more or less a positive one, albeit in a backhanded sort of way. The best line: “The story of Star Wars could be written on the head of a pin and still leave room for the Bible.”

**In fairness, the title is not Dargis’ fault so much as whoever actually chose that headline. Had that line remained as a simple couple sentences in her review only, the review probably wouldn’t have been so controversial. And yet, here we are, talking about it a year later.

“That’s our highest level of film reviewers [who] start to play this little game, this jockeying game, about like ‘Oh but there’s women in it so it’s part of this other thing,’” Stone continued, “Like ‘Dude, that’s a shitty Ghostbusters remake,’ that doesn’t get a good review, like what is wrong with this world?” An outright bad film is good because misogynistic idiots need us to declare it as such, and a bland one is good because we fear what people will think about us if we don’t fall in line with what culture has already agreed is great.

This summer’s current example of this phenomenon is Baby Driver, a very wonderful movie with notable flaws that is being treated as a classic by critics mostly by the nature of its distributor picking a smart release date. Baby Driver – again, a very wonderful movie – is a good action movie with inventive editing techniques and pretty good action sequences with one great one thrown in the mix. In the parlance of five-star reviews, it is a 3.5 star movie that has certain qualities that have caused critics to elevate it to a five star movie: Edgar Wright is a director long appreciated by critics who has never had a true financial success, and this was a movie released right as the annual summer cinematic intellectual property fatigue was kicking in for critics. (Whoever saw Trans5mers on the release schedule a few days before Baby Driver’s eventual release date of June 28 and said “Hey, critics are going to fucking hate that movie, let’s bump ours up to bask in the reactionary glow” is a marketing genius, and I hate calling anybody a ‘marketing genius.’)

Again, I love Baby Driver. My life is built on a strong appreciation of well-crafted 3.5 star movies; the original Ghostbusters is a solid 3.5 star movie, and it’s the first movie I ever loved. This was always the most encouraging amount of stars an action movie could receive when I was a teenager, trying to decide which action movie I should see that weekend. But too many of my conversations about Baby Driver have been about couching expectations against an overblown positive reaction, and I fear this is the boring new world of film conversation I must live in.

(Admittedly, part of this is actually the fault of Rotten Tomatoes. Siskel & Ebert famously created a binary ‘thumbs up or down’ sort of criticism that eventually devolved into the algorithmic Rotten Tomatoes we have today that turns any nuanced criticism into ‘yay’ or ‘nay.’ Studios have been incorrectly blaming this for the domestic failure of a few summer movies – Baywatch, Pirates, The Mummy – but the real problem is that it turns a 3.5 star review into a 5 star review [or a 2.5 star review into a zero]. As long as your review is technically positive, Rotten Tomatoes rounds up for you, and Rotten Tomatoes is where most filmgoers get their criticism these days.)

Another movie I mostly loved that I got into many arguments about towards the end of 2016, La La Land, is the most obvious example to bring up when talking about cinematic and critical expectations. I was lucky enough to see La La Land at TIFF, mostly free of expectations (aside from that of it being Damien Chazelle’s follow-up to Whiplash, a movie I adore), and I fucking loved it. Seeing the opening shot at the back of the Princess of Wales theatre with 2000 people in front of me was fantastic. The next number was almost equally so, even if the rest of the movie wasn’t (although the last number wraps things up well). Pretty much everybody walked out of that theatre excited about what they had seen, and the critical outpour continued for another three months until La La Land’s wide December release. By this time, most people going to see it expected to be walking into the greatest movie of all time, which it is not, and so many of the people I talked to about it in December were underwhelmed because they had been told by so many to prepare to be overwhelmed.

If some equivalent of La La Land had been released in the 1990s, I believe it would have been rapturously received by most of the people I know, because in the 1990s word of mouth generally didn’t start traveling until after the movie hit wide release. Until then, there was nothing beyond, “Yo, I hear this movie’s good.” Take Pulp Fiction, the closest decades-old equivalent to La La Land that I can think of. Pulp Fiction was coming off a Palme D’Or win in Cannes in May of 1994, and it received a wide release in October that same year. This was the second film of a young writer-director whose previous film was a low-budget success story, and this follow-up would be his pastiche tribute to all the things he loved growing up. This pastiche was immediately well-reviewed at a film festival, and then four months later it was released to the general public, essentially the same timeline as La La Land*.

*La La Land had a platform release, which is specifically designed to build word of mouth for a smaller film by opening it in a large market and hoping word spreads by the time its wide release occurs on Christmas. Pulp Fiction was famously wide released immediately, which was (and still is) uncommon for an indie. Also, there were five months between debut and wide release for Pulp Fiction, and only four for La La Land.

With Pulp Fiction, most people would have had access to one early review of Pulp Fiction from their local critic or maybe a Siskel & Ebert segment or whichever Associated Press critic their newspaper acquired for them. The passive film fan would have “Pulp Fiction is supposedly a very good movie” in the back of their head for four to five months before they could see Pulp Fiction, and the more aggressive film lover could read profiles on Quentin Tarantino in Empire magazine if they felt like it. Perhaps the 1990s equivalent of Alex and James would sporadically talk on the phone about how excited they are for this film that they will not have a chance to see until October.

Then, after the film’s release, you would slowly get a variety of dissenting opinions from people who thought Pulp Fiction was overrated or hyperviolent or basically the cinematic equivalent of stylish thievery, but this would happen slowly as you went about your life. You would learn Travis’ opinion when you had a beer with him, or you would learn Graham’s when you went to your office. In the occasional phone conversation you had with your out of town pal Sarah, she would say, “That overdose scene was a little much, but it was good. Jheri curls are inherently hilarious.” Somebody would inevitably be the dissenting opinion, but it would be the minority, and there would be nothing really encouraging you to change yours.

With La La Land, anybody who wanted a deluge of critical opinion could find it in ten seconds, and could then continue to follow it for the four months leading up to the movie’s actual release. At Halloween parties you would talk about how “Apparently La La Land is the best movie of the year,” and little would dissuade you from holding that opinion as more critics discussed it. And then when the movie actually was released in December, you had entirely different expectations, and entirely different conversations. What was once a slow trickle of opinions became a cacophonous void that felt like a thousand voices screaming at you simultaneously. The natural reaction to that is not to join, but to scream a dissenting opinion back at it.

Am I saying La La Land is as good as Pulp Fiction? Not a fucking chance. All I’m saying is that I don’t think they were released on a level playing field (because nothing ever can be).

I can’t say I know why the middle ground in criticism has disappeared, but I have some suspicions. It feels like a middling piece of popular art used to be a common occurrence, but now for some reason the response to anything must be rapturous in some direction or another. Katy Perry’s new album must be terrible, and Jay Z’s must be exceptional, with the latter case seeming to occur much more frequently. Only musicians at the level of HAIM have the luxury of having their new album declared middling, and even that is because Something to Talk About is a tremendously boring album that a lot of critics wished was good (but couldn’t deny it was not and allowed their pre-release hopes to lift their review into the realm of almost-positive). In film, the endless cavalcade of Marvel films are positively reviewed despite being essentially the same film repeatedly*, while the DC films are negatively reviewed until Wonder Woman gave critics a way to feel all high and mighty by positively reviewing an okay film. Most cultural products are simply okay, yet it seems like we must make it feel as though art can only represent two radically different sides of the critical equation.

*The MCU is a textbook example of a collection of 3.5 star films, as they are the equivalent of the 1980s-1990s action movie, a type of movie that was released repeatedly despite being mostly the same. I hardly need to point out that in the 1990s these films were not all positively reviewed; if anything is true, it’s the inverse.

This is the part where I make the obvious comparison to our reactions to art mirroring our reactions to the state of the world. Again, there is no middle ground, as we are all screaming into the void, and nobody gets heard saying something like, “Things are mostly okay.” People want to be memorable, people want to be heard, people want other people to know how they feel about the world. Having an internal dialogue is no longer enough, so we must tell the world. And yet, despite advances in technology, the world can only hear a few voices at any given time, so all of this is fed into our reactions to the work of those voices.

Jay Z’s musical maturation, and by extension 4:44, have become almost a musical equivalent of Lady Ghostbusters, and I recognize I am guilty of making this happen. I love that Jay Z is a hip-hop legacy artist who is (at least now, if not always) pro-LGBTQ, or that he’s encouraging breaking from past genre stereotypes. Saying that stabbing Lance Rivera was a not-ideal move is wonderful to me, as is rapping about investing in real estate instead of going to a strip club. This admittedly comes from a problematic place, given that I am currently the one making some (quiet) noise. I am driving a teal Toyota Tercel with a ‘Honk if you hate noise pollution’ bumper sticker, leading a convoy of garbage trucks filled with cultural criticism. There is no way out of this through words. The speakers have been predetermined, and until we realize that we will forever be screaming into a void.

People want to write their way to a new world, and that’s impossible. Only a few voices really matter, which is kind of what the conversation over 4:44 is continually proving. Sometimes a movie is just a movie, or an album is just an album. But a Jay Z album is still a Jay Z album, thirty-six minutes of words from one of the most widely accepted voices of the last two decades. If we’re all going to listen to one guy, at least he’s willing to be honest and evolve.

Admittedly, I was a bit overly harsh towards this record the first time I heard it. I felt like the music was boringly schizophrenic, like Jay couldn’t decide who he wanted to be (this is further backed up by the first track – it’s called Kill Jay Z partially because he wants to move past the persona people have built for him out of his own music). But then I was walking around listening to it half-drunk while pondering my own meaningless existence, and I realized that even this millionaire isn’t immune to identity crises. He doesn’t know whether or not anything he has done has made the world better, so he has made an album that is explicitly about the world he wants to create. There are countless examples of people imagining a world they want for themselves and those around them not coming true, but it’s cool to see somebody as rich and as famous as Jay Z even being honest about the mere attempt.

We all got excited, we all screamed. Nobody was right, and yet everybody was.