Alex writes about two modernists making films.

“The first time I saw it, it was not like I imagined it – it was something else. It was like a revelation to me. I think it comes down to changing our relationship to movies. Is it still a movie, or is it something else?”

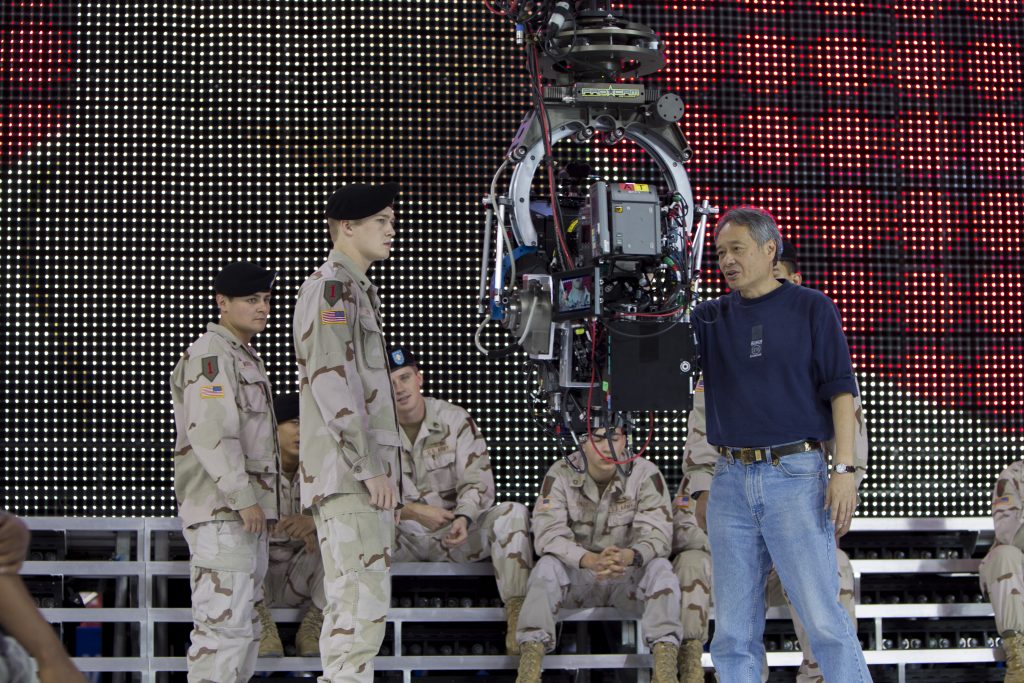

-Ang Lee talking about something that is unquestionably a movie

Sitting through Ang Lee’s latest film, Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, was a puzzling experience for reasons unrelated to the fact that Steve Martin (more or less) played Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones. The film felt like many of those about the Iraq war in any capacity; it felt required to yell its anti-war bona fides, and to yell them exceedingly loudly.

The only people in this film that seem to do any sort of quiet work are Billy himself, Joe Alwyn, and Kristen Stewart, who turns her corrugated cardboard sister character into a person I somehow didn’t hate. Everybody and everything else is much too loud, including Vin Diesel, who manages to be frustrating while playing a mildly tranquilized version of Dom Toretto. The film’s declarations about war are preaching to a long-since-converted choir, and the film’s meta leanings (Chris Tucker spends most of the film negotiating the sale of the various soldiers’ life rights) are not handled with the touch that such things require*.

*Apparently the novel is quite good, and I plan on reading it in the near future. I can easily imagine these elements will be much less problematic in text.

The main reason behind this lack of a deft touch can be at least partially explained by a couple of the film’s technical choices. (As with all people discussing this movie, this is the part where I say I saw the 2D version in 120 frames per second.) Lee wanted to push his technological advances with The Life of Pi even further in his next film. 3D was no longer enough; now he needed that 3D to also be in 4K, and for that 4K to also be projected at a frame rate five times faster than any feature length film has ever been projected.

In fairness to Lee, I have not seen the film in the way he intended it to be seen, because almost nobody has. The 4K, 3D, 120fps version screens in a 300-seat theatre in a New York, a similar one in Los Angeles, and that’s about it. I would be curious to see his ideal version if it played in my city – I would even be willing to sit through this terrible movie again in order to do so – but until it does, I will not. So I saw it in the most newfangled method I had access to, the standard 120fps version.

I have always been dubious about high frame rate projection, despite the fact that Roger Ebert spent the last decade of his life as a champion for it. I can see the appeal of watching sports at sixty frames per second, but the idea of watching a movie at anything higher than twenty-four still seems problematic. The idea of a higher frame rate is to enhance reality – Lee’s stated goal with Billy Lynn was to make the viewer feel like they were living the experience of a soldier* – which I think is basically impossible. When a moviegoer sits down to watch a movie, they know they are sitting in a movie theatre seat, and that seat is their home for two hours. No matter how high the frame rate, we are not going to fucking forget where we are, because we are thinking humans. When I think of the experiences I have had at the movies where I (only momentarily) lose my grasp on where I am, it is specifically because all distractions are removed and I happen to be lucky enough to be watching storytelling that has fully grasped me. And for a person trained on the world of 24fps – which we all are – a high frame rate will always be a distraction.

*Which is a fundamentally disrespectful idea to hold. You will never get a civilian to adequately understand what it feels like to be in war because (and as a civilian, this is admittedly coming from an assumption) actually being in a war is surely more terrifying than any civilian could imagine.

Now, I understand what Lee is doing is difficult. The higher frame rate requires more lighting, and takes more time, and the impressively built 3D camera rig requires so much care that only a few takes of any given scene can be captured. I was present for a tech check for a screening of U.F.O.T.O.G. – Douglas Trumbull’s 120fps, 4K, 3D short film that seems to be what inspired Lee to shoot Billy Lynn this way – and the whole thing seemed difficult to sort out. But you know what? I watched Trumbull’s film, the so-called perfect, immersive filmmaking experience, and I mostly kept thinking about how the short I was watching was objectively terrible.

This is the problem with Billy Lynn. I can’t fully buy into the technology – partially because of my own technophobic biases, I will admit – because the movie itself was terrible. Its time-shifting and metatextual references felt like they were injected because Lee and his screenwriter Jean-Christophe Castelli just saw their first Charlie Kaufman movie and got all amped up about it. I am not saying I will never buy into this technology, per se, I am merely saying that I never could until the movie they filmed it with was actually good.

“Any time you [shoot] outside, you have no control, or at least 50-percent less control. For example, we shot one exterior in London as an establishing shot of the city. I figured it would be raining, but that would be okay because that is perfect to establish London. But the day we scheduled it, of course, it was a bald, perfect sky. We ended up having to deal with crane and camera shadows. So no matter what you do outside, in my opinion you have to compromise three to four times more than when you are in a controlled environment.”

-Robert Zemeckis, attempting a fundamentally impossible quest

Robert Zemeckis’ new film Allied is a not-terrible movie that uses technology in a similarly innovative way to what Lee did. To shoot the film, Zemeckis tried to capture the entire film on a soundstage, filling in the blanks with effects. Allied is far from perfect, but it works as a simple spy movie starring a couple of engaging stars. It even (almost) avoids emotionally over-the-top sequences; the film only goes Full Zemeckis in its final minutes.

Sitting in that film, I knew less about the process used to make it than I did for Lee’s. I knew Zemeckis would try to be technologically innovative in some capacity, because that’s just how homeboy works these days, but I wasn’t entirely sure how. At times, I could tell that much of what I was seeing wasn’t real per se, mere digital matte paintings thrown on top of blue screens, but after the film was over I found out it was a lot more than I had guessed.

Now, that didn’t change how I felt about the movie all that much, but it certainly made my feelings about the movie more clear. Watching Allied, it felt like a good movie that had been sterilized. Everything felt too clean to be a world, even though Zemeckis and his team were more or less creating a version of our world from scratch. It was certainly better than Zemeckis’ uncanny valley-challenging films The Polar Express and Beowulf – with the exception of a baby, nobody in the forefront of Allied is egregiously computer generated – but there was an unceasing feeling of sterility that plagued the film. For a movie about humanity’s imperfections, it felt too perfect.

This is why Zemeckis and other technology-loving auteurs like James Cameron like to make their movies on a soundstage: directors are perfectionists, and not having to engage with the real world means not having to contend with real world issues. In Allied, the limits of the weather don’t have to be considered, because there’s a roof covering the shoot, a roof that also features a sprinkler setup to pour rain if the scene calls for it. You don’t have to use a series of gigantic fans and risk blinding Marion Cotillard with a renegade grain of sand, you simply add the sand to the shot later.

During the studio era, films were made almost exclusively on studio grounds because of various technical limitations. Cameras were larger, the significant power needed for lights was harder to find, and nobody wanted to wait around forever to get one shot (this was a time when directors would consistently release four films a year because the factory-style efficiency let them work faster). Films were consistently made in such an unreal world that when Citizen Kane featured low angle shots that showed a room’s ceiling, it was considered revolutionary.

As film equipment got better, directors were able to take it out into the real world and allow their films a heightened sense of realism that comes with that. Movies tried to avoid sound stages when possible, because the problems of dealing with locations became worth it to get your film some added authenticity. But now, we seem to (slowly) be going back to the studio age – with so many big budget superhero bonanzas relying on the soundstage production method, it’s only a matter of time before more directors do the same. (It’s entirely possible that location vs. soundstage becomes a film vs. digital style argument in the future.)

Again, directors are perfectionists. When somebody like Zemeckis sees a way to give him more control over his environment, he’ll take it. The saying goes that art imitates life, but when artists attempt to do so with too much digital imitation, the lack of an imperceptible, realistic touch will continue to hold the art back. There is no true perfection in life, so expecting that out of your cinema is a fool’s quest. You can create your perfect, sterile world, but that constructed perfection will end up being the source of your film’s imperfection.