Alex writes about Rob Reiner, specifically his string of late 1980s and early 1990s successes.

Recently, as I was completing the final days of my annual gig trouncing the red carpets of the Toronto International Film Festival, I saw something that interested me. A group of patrons near me were being asked a variety of trivia questions, questions about people that were showing up for the evening’s coming film. On most evenings, these questions were easier than falling asleep during Oliver Stone’s Snowden, but one query got posed that nobody had the correct answer to.

“Which Rob Reiner-directed film was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture?” asked the ringleader.

“Stand by Me!” shouted a contestant. No.

“The Princess Bride!” No.

“The Bucket List!” Obviously not, you dummy.

This is Spinal Tap, When Harry Met Sally, and Misery were all listed. After a pause, The American President was named (although it never really sounded like that person even believed they could be right). I had been listening in on this whole thing, so I started to go through all the Reiner movies I could think of.

Ghosts of Mississippi. No.

North. Not a chance.

Alex & Emma… Isn’t that movie about incestuous time-traveling*?

*No. That’s Kate & Leopold, which is a James Mangold film.

I was stumped. I was among the crowd, scratching my head, thinking the gift of free Lindt chocolate would never be bestowed upon us. Once again, the man with the answers spoke, realizing we were collectively out of ideas.

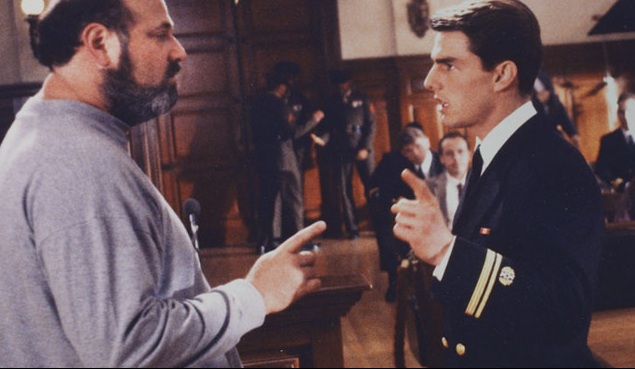

“The correct answer is A Few Good Men.”

Everybody groaned. Of course it is. It could not have been more obvious, but I still couldn’t notice it, even though it was staring me right in the face.

As I continued to stand around, waiting for Rob Reiner to show up to promote his latest film LBJ, I began running through that list of answers in my head. I started thinking about Reiner’s career as a whole, possibly for the first time in my life. As a man obsessed with directorial arcs, I somehow never considered Reiner’s, even though he released the following five films consecutively from 1986 to 1992:

- Stand by Me

- The Princess Bride

- When Harry Met Sally…

- Misery

- A Few Good Men

All of these films were cultural moments in and of themselves. The least famous of those five movies might be Misery, and even that had a cultural moment of its own. Each of these films feature scenes that still get quoted without relent today, decades later. With the requisite few outliers, pretty much everybody likes these films. They were all hits. They were critically acclaimed, and each of them was nominated for at least one Academy Award. When asking a random person on the street about these films, I would imagine the average North American could describe a scene from at least three of them. But what that average person, or what the film-obsessed lunatics like myself never remember, is who directed those films. There’s always something else standing in the way.

In the late 1990s, Steven Soderbergh started a run of five films that I frequently cite as one of the more impressive runs in Hollywood. Starting with Out of Sight and The Limey, he moved on to his Oscar-bait phase with Erin Brockovich and Traffic, before using his newfound clout to play pranks with George Clooney in Vegas while filming Ocean’s Eleven.

I adore Steven Soderbergh. If given the hypothetical to have experienced any filmmaker’s career, his would make the top five, even knowing that I would need to stomach having directed The Underneath. I would never consider Rob Reiner among that top five, not for a second, even once I acknowledge that he also directed This is Spinal Tap.

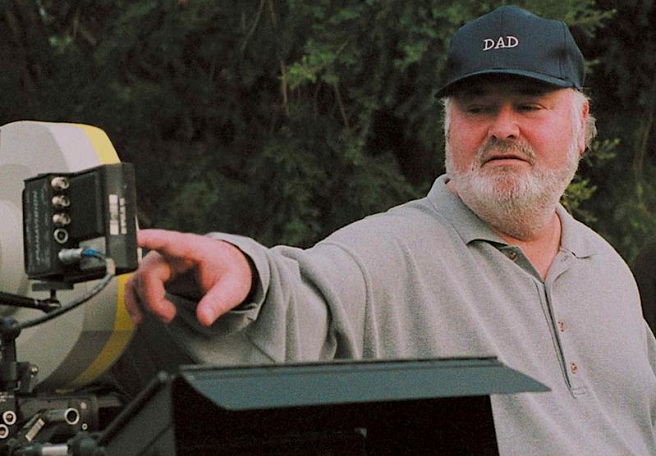

Rob Reiner has directed six unquestioned classics. And yet when they come up in discussion – even with people that like to talk about the talent behind the curtain – Reiner almost never gets mentioned. In a culture where critics and non-critics such as myself build opinions entirely on who is directing the film, why don’t we discuss this particular director?

As the son of Carl, Rob Reiner has been in Hollywood for basically his whole life. As a twenty-one year old, Reiner was writing for the (by 1960s standards) subversive Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, followed by a successful transition into acting as Meathead in All in the Family (a show that was the most popular show on television for half a decade). After this he made a move into filmmaking, with This is Spinal Tap as his debut feature, beginning his run as perhaps the most notable non-auteur in Hollywood.

By the time Reiner started directing, he was already famous; he had been in Hollywood for almost twenty years, and he had won multiple Emmy awards. Had Reiner’s career ended in 1978, it would have still have to be considered phenomenally successful. He has since directed 19 films, six of which are well-remembered classics. Reiner might be the most successful modern(ish) director we never talk about.

When looking for a shared theme among Reiner’s films, the simple thing to point to is that there really isn’t one other than the fact that each is about human beings. These are all relatively simple, entertaining movies. Reiner has never attempted to make anything byzantine like Memento; his most expansive film is probably North, which plays like a movie for drunk children. When watching any of Reiner’s films, there is no discernible style to attach to them; each film (with the exception of the stylistically inventive Spinal Tap) looks pretty much exactly how films of its time period looked collectively. If you need a Hollywood time capsule for 1992, look at A Few Good Men: the only (brief) action sequence is shot with hilarious orange-boosting filters and absurd music, and the movie features Demi Moore in a prominent role. Nothing jumps out as inventive, but nothing jumps out as bad either. But watching any one of Reiner’s other films does not give you much to link to A Few Good Men; Misery looks and feels totally different. In each of Reiner’s films, the shots are relatively simple, and the visual language of film isn’t all that complicated. Reiner is but a man with a camera, making movies as he sees fit, and what is seen fit by his eyes is often not all that showy.

The most obvious common trend in looking through Reiner’s career is that, in his most notable works, he is surrounded by filmmakers who are more famous than he is. This is Spinal Tap – a failure upon its initial release that has since turned into, well, Spinal Tap – has retroactively been turned into a Christopher Guest movie. Stand by Me and Misery are both seen as Stephen King movies, and in the case of the latter, Kathy Bates’ entertaining performance dominated any post-screening discussion of the film. Even watching Misery today, I couldn’t help but think “Well, I guess this is how Stephen King thinks about fandom*,” even though I watched the film to specifically try to read Reiner’s thesis. Like with many of his other films, Reiner blends in so well that you want to talk about others instead, even when your goal is specifically to try to talk about Reiner himself.

*Whereas in other cases, specifically The Shining, I never think about Stephen King. When I think about that film, I exclusively view it as a Stanley Kubrick film that King happened to provide the genesis for, even though King is more famous than Kubrick.

When Harry Met Sally was written by Nora Ephron, and it felt like such a script-based film that Reiner’s contributions are now mostly ignored critically. Ditto for The Princess Bride, written by a post-All the President’s Men William Goldman. A Few Good Men was written by newly-minted playwright superstar Aaron Sorkin. In discussions of all of Reiner’s movies, the talent listed first never seems to be Rob Reiner. In the case of A Few Good Men – simultaneously Reiner’s most critically and commercial successful film – he might rank fifth (or sixth if the person you’re talking to happens to love Kevin Bacon).

Which almost self-imposes the questions: is Reiner actually a talented director? Or merely smart enough to stay out of the way of other incredibly talented people?

The first question is obviously idiotic. Lightning doesn’t strike twice, let alone six times; ipso facto, Rob Reiner is talented. The answer to the second question is also yes, which might be a talent in and of itself.

Throughout his career, Reiner has never seemed less than normal. He is an adorable, approachable man. Physically he never looked like a star, even as a younger man, which allowed him to thrive on a television show that was popular specifically because of how normal everything was intended to seem. As a director, Reiner has made films about normal people, and he has made them in simple, easy to digest ways. When he is working with an exceptionally talented person, he is willing to let their ideas drive the metaphorical car; if there is one defining trait running through Reiner’s career, it seems to be that he is a realist. Reiner is able to take the work of the abnormally talented, and put them through his own filter to allow them to excel.

When you’re twenty-one, a lot of bizarre things can appear to be normal, depending on what environment you’re in. It’s an age where it seems like drinking two litres of Slurpee every day is not insane, or that liking Jack Johnson’s music doesn’t immediately make you a dummy. At a comparable age, Reiner was writing on Smothers Brothers. By the time Rob was three, his father Carl was writing and performing on Sid Caesar’s Show of Shows, so Rob was deeply entrenched in Hollywood before he was old enough to realize how weird that fucking place is. Surely at this point – as a 69-year-old man – he is able to look back with clarity on the abnormal arc of his life, but that he can’t remember a time when his family wasn’t involved in show business in some capacity surely increases the feeling of normalcy toward his own work. Rob Reiner probably sees his job as just that – a job – albeit an exceptionally cool one that many are envious of.

I am continually fascinated by the moment when a director is coming off a colossal success. In this one brief moment said filmmaker is able to get a film they truly believe in greenlit, even if that film is a little more odd than the studio in question would like. When the talent is hot, a studio will often give them the benefit of the doubt. Think Mike Nichols making an all-time auteurist bonanza with Catch-22 after the collected success of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf and The Graduate, or Francis Ford Copolla making The Conversation after The Godfather (or Apocalypse Now after The Godfather Part II), or M. Night Shymalan following The Sixth Sense with Unbreakable. If James Cameron had wanted to follow Avatar with a $200 million dollar virtual reality biopic about my career as a video store clerk, he probably could have gotten 20th Century Fox to pony up. Which is only slightly less idiotic than Rob Reiner choosing to follow his biggest success A Few Good Men with North.

Now, North is not all terrible. The idea at the core of the film – that of an overachieving child essentially declaring free agency from his parents, and taking a variety of pitches not unlike Kevin Durant did this past summer – is (potentially) appealing to me. Had Wes Anderson and Owen Wilson been given this script and $20 million in 1998, I’m certain they would have rewritten it into something good. But as it stands, North is a terrible fucking movie. The jokes running throughout the film are almost uniformly unfunny. Kathy Bates and Abe Vigoda show up in Inuitface, and the Fed Ex product placement* makes the end of Cast Away seem subtle. North is a terrible movie, and was reviewed as such. It made no money. It essentially killed Reiner’s hot streak, sending him back into the arms of Aaron Sorkin and The American President, a film that feels even more Sorkin-y than their previous collaboration**. Since then, Reiner’s (critical and commercial) failures greatly outnumber his successes.

*Which, when the story of the film turns out to be a dream, means that Elijah Wood’s dreams are extremely pro-ground shipping. Admittedly, assuming a child in the 1990s would have product placement-infected dreams is legitimately interesting.

**If somebody who was aware of the North American pop culture landscape – but had absolutely no knowledge of that film – watched a version of The American President without credits today, I can only imagine they would assume Sorkin had directed it himself.

It is impossible to write this piece without sounding like I’m insulting Reiner; it also probably reads like I’m writing about Reiner as if he is already dead. I realize that by writing about how unimportant he is seen, my promotion of his career as a whole can only read one way. But I want to be clear: Rob Reiner is cool in my books. He has never been the most notable cog in his own career, that much is true, but he also gets to be Rob Reiner. He is a genuinely hilarious man who everybody seems to like. He has directed six classic films. If nothing else, Reiner basically invented the Sorkin walk and talk in A Few Good Men, so we owe him one for that.

In a recent interview with The AV Club, Reiner talks about some of his more personal contributions to his work. To Reiner, Misery is about the limitations of one’s fame, and he views Stand by Me as his masterpiece because he felt it was the film where his own sensibility shined through the most. These are not things I get out of his films, but it does to some extent devalue my opinion of them. I would never assume there is nothing personal in Reiner’s work – in order to dedicate a year of your life to a film, you also have to be willing to put some of your life into that film – but I know that his personal contributions are not the things that shine through the most. If nothing else, his most successful run of films basically proves that what keeps him happy and comfortable, at least for a time, also made America happy and comfortable. Reiner didn’t necessarily know what the people wanted, and yet he still consistently gave it to them. He kept working how he wanted to, and it worked out enough to keep him happy.

Throughout TIFF, I would hang out with a wonderful British editor named Credenza, who I have worked with at the Festival for years. Since we only see each other during said Festival, I would come and hang out with her after my shift, basically making it impossible for her to work. A consistent argument between the two of us was built around how she saw our careers – she felt that it was our obligation to ourselves to continually try to excel in the most difficult environment possible. (If she knew anything about baseball, she surely would have employed a metaphor about being called up from the minor leagues.)

Naturally, I disagreed.

This is the feeling I get from Rob Reiner’s career. He does the work that he wants because he can make it happen, and if it happens to connect with others, that’s wonderful. Reiner does not easily fit into the arc of the auteur we have all come to accept as essential to film criticism, and perhaps that bothers him a little. But I suspect the opposite. The minor leagues are just fine with certain players, so long as they get to stay on a good team for a while. This is a man who feels consistently content with his life, a man who simply wants to keep doing what he has always loved doing. Sometimes that will work out for him, and sometimes he will fail. But the man cares not. The man simply keeps going.