Alex writes about Adele, Justin Bieber, Shia LaBeouf, and youthful idiocy.

“It’s so typical of me to talk about myself, I’m sorry.”

-Someone who dwells.

“Can we both say the words and forget this?”

-Someone who wants this to be over.

“This shit changed my coffee order name, which in turn, changed my sense of self.”

-Someone who is in flux.

It started with a tweet, as it does.

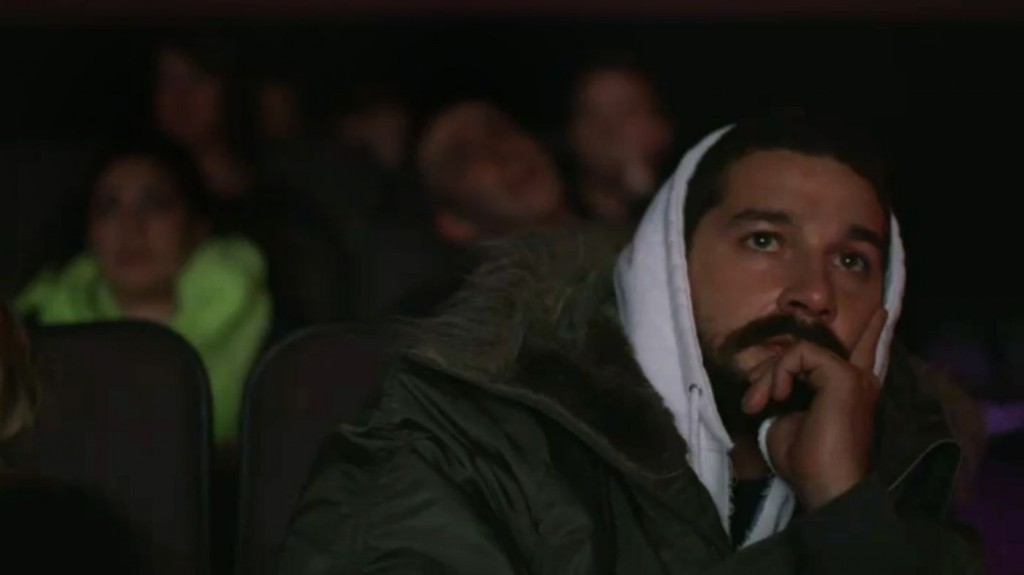

Shia LaBeouf was sitting in cinema six inside the Angelika Film Center in New York, and he was starting to watch all of the films in his career in reverse-chronological order. Throughout the whole ordeal, a camera live-streamed his visage to us online, putting LaBeouf’s emotions, naps, and pepperoni and jalapeno pizza consumption on our laptop screens. As perhaps the world’s foremost scholar on the career of LaBeouf, this immediately fascinated me. I (very briefly) considered going to New York to try to get in the theatre as Shia was hitting 2007 – the golden year in the books of LaBeoufian lore – before logic crept into frame.

Now, LaBeouf has done a lot of dumb stuff in the name of his meta-modernistic pursuits. I know this. The paper bag shit was equal parts funny and silly, and an actor taking a role in a Lars von Trier movie has never made me like them more. But I must have liked something about #ALLMYMOVIES, because I checked in with the livestream semi-constantly while I was working, eating, or between episodes of Curb Your Enthusiasm throughout the week. I never actively watched the stream for more than a few minutes at a time, but I continually found it interesting. What it lacked in bombast, it made up for in quiet intrigue.

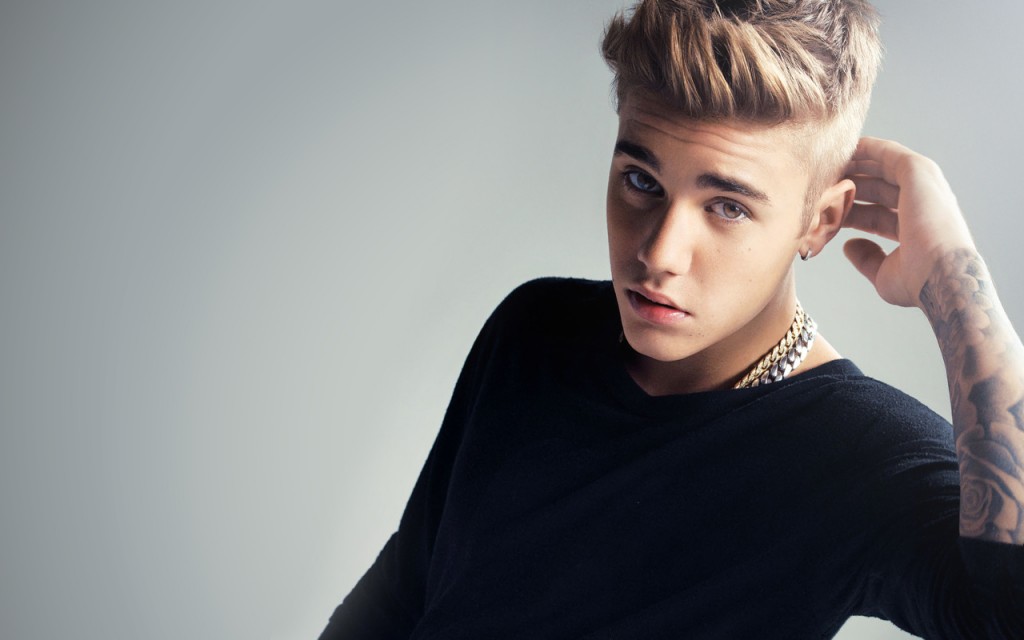

When the Jack U track Where Are U Now hit the digital streets in the summer, a couple of things were apparent: this song is thoroughly enjoyable, and Justin Bieber’s voice sounds surprisingly low in the mix. This was intriguing to me, as it seemed like maybe Bieber was okay with his own role in a song being minimized, an intriguing take for a musical superstar of his stature to have. (It’s not exactly Michael Jackson singing backup for Rockwell, but it was intriguing nonetheless.) Bieber seemed to be – and sounded like – a featured artist, as opposed to the person on the head of the dais. He was technically featured on a Skrillex/Diplo collaboration, but that pair obviously knew Bieber’s name was more important than theirs, and the marketing materials reflected Bieber’s stardom. The Canadian wunderkind’s face is the only one present in the music video. He was allegedly the main attraction, and yet he was being tuned out.

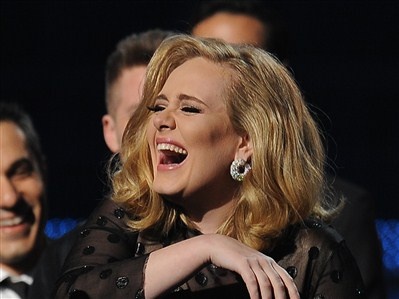

In May, the Internet’s collective heart was all aflutter when it became clear that Adele was making her triumphant return to the pop music charts. The queen of belting was back. This would not be a confusingly mixed record, and when her single Hello was released in late October, it was clear that Adele was here to push her way back into our collective hearts. Her voice was unquestionably the main attraction, and as such it was turned up to eleven.

Adele and Justin Bieber are both fighting for the same slice of earworm-infested pie, but they are doing so in dramatically different ways. I refuse to see these contrasting approaches to production as mere coincidence.

Bieber’s Purpose and Adele’s 25 are currently metaphorically burning up a variety of charts, with Bieber going gold in week one, and Adele unprecedentedly going over a quarter of the way to diamond in her opening week*. Their records are good in their own way, with a handful of winners alongside a couple of duds about Jesus and/or children. Each work sounds like a multi-million dollar album that has been edited and re-edited with ProTools, as they are, mastered for maximum cleanliness in a modern music world that demands that its pop sound pristine. These are to be the sounds of the times, so they must sound like the time.

Bieber’s Purpose and Adele’s 25 are currently metaphorically burning up a variety of charts, with Bieber going gold in week one, and Adele unprecedentedly going over a quarter of the way to diamond in her opening week*. Their records are good in their own way, with a handful of winners alongside a couple of duds about Jesus and/or children. Each work sounds like a multi-million dollar album that has been edited and re-edited with ProTools, as they are, mastered for maximum cleanliness in a modern music world that demands that its pop sound pristine. These are to be the sounds of the times, so they must sound like the time.

*It cannot be understated how surprising Adele’s sales are, even as it is being stated constantly. It still makes no sense to me that her album could sell so many copies; a pro-Adele Illuminati conspiracy seems more believable than what actually happened.

Bieber’s is the album that sounds most obviously crisp and altered, of course, if only because his music tends to involve more modern technology present at the forefront than Adele’s. Biebs is primarily making music for the kids, after all, and the kids love them bleeps and bloops. What has been most fascinating in listening to a number of the most prominent songs has been Bieber’s willingness to fade into the background of his own music. There are still a handful of ballads where his voice is the star, but the songs that are going to be the most notable – singles What Do You Mean?, Sorry, and the aforementioned Where Are U Now – sound like dance tracks that Bieber just happens to be singing on. Even on album cuts like Children and Company, it sometimes feels like Bieber heard his fruitful collaboration with Skrillex and Diplo and knew that he should give himself over to the throes of modernity. (As such, Skrillex is a credited producer on five songs on Purpose, the most of any producer.)

In a fascinating New York Times piece about the creation of Where Are U Now, Diplo outlines the genesis of the song, which starts with a Fashion Week run-in, a couple of emails between managers, and a file download.

Bieber was involved in some capacity, and yet hardly involved. He wrote a song, and then somebody took all the various pieces, moved them around to their liking, put Bieber’s voice through a dolphin filter as the hook, and turned it into one of the biggest pop songs of the year. This is not uncommon – dance instrumentalists constantly minimalize their vocalists’ contributions – but it’s odd that such a big star would be willingly caught up in this. When Bieber was actually re-recording parts of the song himself, he would do it a line at a time so his collaborators would have a clean line to do whatever they needed to do with it.

Stars give into trends frequently, but such big stars don’t tend to dive headfirst into trends that minimize their own contributions. That said, it is unsurprising that a man who is unsure of his stature in the modern pop landscape would be so willing to go where the trend dictates.

Adele doesn’t play the trend game, though. She might have a Max Martin track on her record, and Danger Mouse shows up too, but they all get thrown through the Adele filter as opposed to the other way around. Ms. Adkins knows who she is, and we all love her for it. She is talented, she is charming, she is a pop colossus. All of these things are inarguable, we have decided. Adele projects an image of constant, vigilant control over her own being. She is wise beyond her years, so she doesn’t have to deal with the foolishness of youth. As such, her record is about a twenty-five year-old dealing with the fact that their youth is over.

If nothing else, 25 is almost humourously pointed. Adele consistently sings about the past in a mournful way; if 21 was infamously about her anger and sadness over a breakup, 25 is about the regret that a time of being so emotional and impulsive has passed her by. The record starts with Hello, a song that is an interesting apology to the person she wrote a whole, phenomenally popular record about years ago, a person that will forever go to his friends’ weddings and have to dance to songs about himself*. Adele holds onto this motif of looking back throughout the record, constantly talking about a youth that has passed her by, as she is now a woman raising a child. When We Were Young hits this note pretty obviously, All I Ask slightly less pointedly (and therefore more interestingly).

*Imagine being on a dance floor as Rolling in the Deep plays and you see a large group of people ecstatically dancing to a song about how you’re a terrible person.

Even when she’s singing about a love that’s slipping away from her, Adele is singing about the capacity to love a way she once did. She’s not just photographing you in this light because she wants a keepsake of your time together, she’s doing it because she’s concerned the next camera won’t be able to adequately capture the textures of magic hour blue.

It’s all very sweeping and saccharine and sad, because these thoughts are coming from somebody who isn’t even all that old to begin with. The core idea of the record is that, even at 25, you have realized everything ends. You are no longer who you used to be, and you never will be again. That was a million years ago.

When I listen to Adele’s new album, I hear songs I didn’t think I would ever like. I wasn’t big on 19, and I cared little for 21. This music is so weirdly old-fashioned, and it’s in a genre I never liked anyway; my favourite brand of singer has never been the solo diva. I am perplexed as to why I like Hello and When We Were Young as much as I do. The guitar in A Million Years Ago sounds like it should score a Nespresso commercial. I hear the individual parts and I think, “This is insane. The backup vocals come in exactly when I expect them to, and so do the strings. Those drums are so lame. This is the pop music equivalent of those John Williams scores I complain about.”

I get it, but I don’t get it.

With Bieber’s record, I get it. I hear it and I can break it down easily. He might be lost in the mix of his own song in Where Are U Now, but the song itself is still pleasurable to listen to. Sorry is a jam, and those surprise horns in Love Yourself are a wonderful touch. There are more out and out unlistenable songs here, but on the whole, Purpose is a pretty decent listen. That said, the apology motif that runs through the record is pretty god damn annoying.

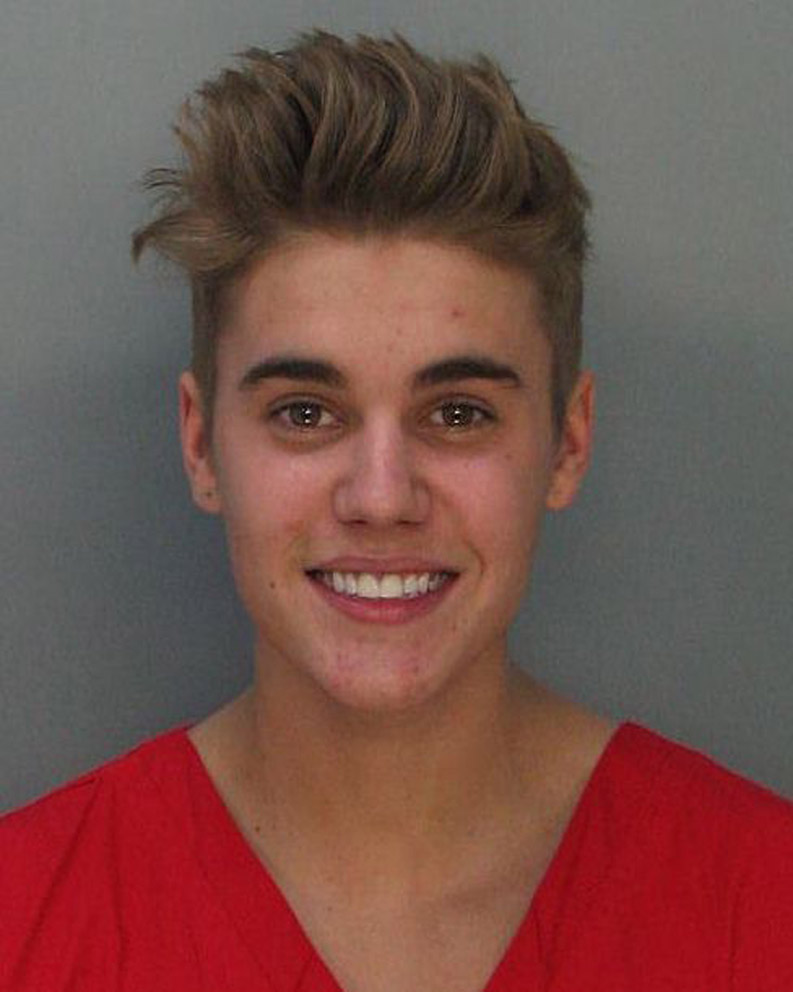

If Adele’s album is a humourously pointed look at her past, Bieber’s is an eye-rollingly pointed apology letter for his more unruly actions of the past few years. In seemingly every review of Purpose, Bieber’s various legal troubles must be mentioned. As such, I will do so now. There was some shit with a monkey, a really funny mug shot, an even funnier deposition, and I think an egg throwing incident. He’s wanted in Argentina. Parents were afraid of their children’s idol. Keyshawn Johnson was angered, and we temporarily cared about his feelings for some reason. When he was eventually roasted on Comedy Central, Justin Bieber even derailed the whole thing by turning his own time on the stage into a prolonged apology about what he has done in the past, and how he hopes to move on. Purpose is merely a poppier continuance of that same pontificating.

What Bieber is doing with Purpose is apologizing for what he’s done in the past, and trying to blend in with the present better. He is allowing people to turn the sound of his own voice down, because he feels it will help him blend in better with the modern landscape. He can still be the face if need be*, but he has to give up some of the control sometimes. It has become clear that he lacks self-control, so he lets others control himself for the preservation of his career. At this point, sticking out only seems to make Bieber’s life more difficult.

*Although the Purpose Movement videos indicate he frequently doesn’t need to be.

Adele sees her regrets, too, and she knows she’s past them. She will continue to move forward as – despite being such a classical artist – that seems to be the only direction she moves. Her next album will not be 12, a treatise on the fumbled joys of childhood.

Justin Bieber is in a state of middling though – he doesn’t quite know where he belongs in culture, in his videos, in his own goddamn music. He’s still too young to have clarity within such an old world.

Shia LaBeouf was watching his constructed life in reverse, for a new construction that he was (at least partially) in charge of. He submitted himself to his collaborator’s wishes, and what we got out of it was equal parts odd and intriguing. He was sitting still while rolling backwards through his own memories.

I like to think I am not one to guess what people are feeling, but realistically I know I do it constantly, and as such will do it again now. I suspect Shia LaBeouf has a couple regrets in how he ran his earlier career, but I mostly think that is tied into wishing he hadn’t signed such an extensive Transformers contract. He probably hates that he was in Eagle Eye because that movie was – in the parlance of its time – a pile of hot garbage. But the problems of his past have lead to the successes of his present (and future), and as such I believe he has come to terms with this. The beautiful Elastic Heart video he was in builds on all of these things – a child star trapped in a cage of their own image who is now too old, too grown to slip through the cracks and restart – and I’m sure he has no regrets about that.

In some cases, the result is worth the confusion.

So what makes Adele so unprecedentedly likeable? Well, she sometimes makes really good songs, which certainly helps. But she’s also a relatively young person who seems smart enough to be a middle-aged woman; the kids can love her because she still seems young, and the adults can love her because she’s not as dumb as a kid*. She is the new old thing. Adele is self-conscious, clever, and seemingly always aware of how things appear from the outside. She never actively appears to want to be famous, but also doesn’t hide from her fame. All of these factors are important. Adele is everything we need our modern, likeable superstars to be.

*This is similar to how people both young and old adored Lorde; she’s young, but never in an idiotic way.

The music video for Hello best illustrates her self-awareness of the old world position she has built for herself on the charts. As she stands in the forest in the video, with autumnal leaves blowing around her ankles, the amount of foliage is at comical, Midler-in-1987 levels. Her coat is ridiculous, and the wind machine on set is probably louder than Adele herself. Through all of this, Adele plays it straight, but it’s clear she knows how silly it all is. Her laugh is a booming cackle of self-awareness, so we’re all aware that Adele is smart enough to know that’s way too many fucking leaves, Xavier Dolan, calm down please.

As she wraps her ultra-serious performance of the same song on Saturday Night Live, she breaks, making the most charming, “What the hell is going on?” face she can. Adele is focused on being a part of the old world, but her success is predicated on her reminding us that she remembers that world is gone. That all of this is obvious without being too obvious is precisely why we like her.

With Bieber, the humour always seems unintentional. I can’t watch him mug at the camera without laughing, specifically because I don’t think he knows he’s being funny. When he cries out “Be more straight forward!” toward the end of What Do You Mean, I laugh every time, and I’m certain this is not his desired reaction. As a skater goes for a clearly unplanned high five during the video, Bieber’s surprised expression looks like somebody who is never ready for the unplanned. Bieber is unliked because he never seems to know what he wants. He is just another dumb, famous kid, so intelligent adults hate him.

When he began his initial, prodigal stages on YouTube, Biebs was pegged as a multi-instrumentalist wunderkind, the type of kid people watch competition reality shows to discover. He was a not-yet-man of many talents, who Usher then groomed into a modern pop god. Bieber was discovered via modernity, but his more traditional skills were what got him seen initially. We hate him for the disappearance of the latter, and the embracing of the former. Giving in fully to modernity is the only way to get us back onboard, Bieber thinks. He must let Skrillex drown him out.

My initial reaction to Adele’s first-week success was one of a cheer for the old world. She cockblocked modernity and somehow ended up bringing an old fashioned sales record that many have proclaimed for years would never be broken. I would probably react the same way if – regardless of the film’s content – The Hateful Eight’s 70mm projections somehow became the biggest box office hit of the decade*. I am forever a contrarian, always rooting for what seems unloved, and purchasing albums is an action that is now distinctly unloved. I fawned over digital cinematography in its infancy, and now that it has taken over I am staunchly pro-film. But this will all be a blip; the bleeps and bloops have won. The music industry is long since dead, no matter what Adele has to say about it.

*This is basically impossible, but I thought Adele’s sales were too, so who the fuck knows anymore.

By withholding her record from streaming services, Adele was able to break unbreakable records. But this traditionalism has its negative effects as well. By holding onto the old world too long, you can hinder the new one that will happen whether you accept it or not. The music industry died because it didn’t give into modernity quickly enough; I am dismayed by the state of movies because the studios didn’t survey all of their moneymaking options early enough, and I am now subjected to a world of cinematic homogeneity. Adele’s record is the one star still able to shine this bright, though, so she will hold onto it until she absolutely must let go.

Adele knows what she’s doing, sure, but she’s the only one that’s able to do it. She is what Star Wars will be: an unparalleled hit simply because it brings together enough, long-held common interests. We will all go to the theatre because on December 18th, it is the only place to get what we all collectively want. But this is an outlier; it will be the highest grossing film in movie history, but it will not solve the problems of cinema. If anything, it will make them worse. As myriad writers have pointed out in pieces about her sales, Adele holding out hinders future artists by keeping consumers away from modern alternatives like streaming services. Your mom would be on Spotify right now if Adele had given them 25 immediately.

But of course if Adele could be fairly compensated for doing so, I’m sure she would have, so we’re all just floundering, really. She does things the tried and true way because the new normal is still fluctuating. Right now, the only thing that makes sense for Adele to do is remain in control for herself.

We all want to believe we are Adele, a person in control of our lives, viewing these modern absurdities from our ivory observational perch. But the truth is we’re all much closer to Bieber. We’re flailing around, trying to figure out where we fit inside this crazy, nonsensical world. Adele has enough distance to see where she fits, and we like to think we’re so lucky. But we’re not. We’re dummies, sitting in the dark looking anywhere we can for a reflection of ourselves.

I suspect that a handful of years from now, as people of my generation are pondering the follies of their twenties, they will sit back and think about how hilarious it is that we all decided it was a good idea to try to start online publications. This particular website will one day become a more intelligent version of that GeoCities site I made about my favourite pro wrestlers in 1998. We are making content, hoping that it will catch fire, even though we all have to be smart enough to know that will never happen. There can only be a few media empires, and the sitting leaders of that group are specifically designed to stop more of them from existing. Writing in your bedroom with Woodford Reserve and a laptop is the new plucking in the garage with a guitar and some Miller High Life. We’re all members of terrible garage bands, and our music is embarrassing and unlistenable.

The number of ‘publications’ I have written for is idiotic, and most of those publications themselves were idiotic; some of the people I wrote for are full-on idiots*. We tried to create this little bubble of collective thought, not realizing that since we were doing the same thing as everybody else, it meant nothing. There is a multitude of bubbles; we are simply all in our own now. Whenever people say, “I can’t believe people actually think this,” I am resorted to pointing out that we all have the power to create our own sphere of influence, so it’s silly to believe others don’t do the same. We are all Donald Trump, imagining thousands of Muslims pointing at their televisions and cheering on 9/11, not understanding why people refuse to believe us.

*Not you, Brady. The exception proves the rule.

I still write and I still podcast because James and I enjoy it as a hobby; we believe we’re doing a good job, so we keep doing it, regardless of who listens. But I am making the world a worse place. Caring about such inanity is insanity. We are contributing to the ever-escalating wall of noise that makes it seem like nothing will ever make sense. I am doing that right now, and I know this, but I am not going to stop. I’m saying something because it’s better than doing nothing, but the something I choose to write about is nothing.

Even if it’s at the fringes, though, for some reason this noise must still be there.

After Shia LaBeouf came out of screening room six at the Angelika Film Center, he did a joint interview with his collaborative partners, Nastja Sade Ronkko and Luke Turner, which was published on NewHive, the host of the #ALLMYMOVIES stream. There was much silliness and talk of artful pizza, but there was also a lot of talk about community. The goal of the prolonged piece seemed to be exactly what I like about going to the movies: to bring people together in pursuit of a common goal. To – if only temporarily, if only for the 105 minutes of Disturbia’s runtime – fully understand the world you inhabit.

LaBeouf talked about how he said initially people were focused on his own reactions – people come to the theatre to see the stars, after all – but over time it became this thing they were all in together. They were collectively experiencing a movie, it just so happened one of the performers was there for the experience too. The viewers established a quiet bond simply because they were physically doing the same thing at the same time. I have done overnight movie marathons, and I understand this feeling entirely. It is exhausting and potentially diabetic, but it is wonderful and difficult to attain.

I find it impossible to hate on anybody for trying to provide that feeling to another person, even if that person ends up being an outlier.

In his review of 25, Jon Caramanica expertly breaks down the appeal of Adele:

“Pop moves and mutates, but Adele more or less does not. Naming her albums for different ages in her life doesn’t indicate radical changes from era to era, but rather reinforces the reassuringly slow march of time. Her music is like time-lapse photography of a busy street: Small parts move, but the structure of the whole picture remains essentially intact.”

Adele reminds us of a world we want to believe in, a world that is still within our grasp. Change isn’t happening too quickly here, because this is a compact disc. The songs contained within might not be happy, but at least we understand the pieces that churn together to make that choir of sadness sing. Adele simultaneously grasps the world as we want it to be and the world that actually is.

We miss the past, the traditional medium, the idea of being younger than we are, if only because it always seems like things made sense when we view the past through the rose-coloured glasses of our faulty memories. We are all constantly saying goodbye to a world that has already passed us by, quietly wishing that it hadn’t. We pick up the newness as a signifier of how we miss the old. But this world is gone. We must give in, as much as we refuse to.

As Adele sang to a bigger crowd than ever before, it was only because she was an all-time outlier. Her perseverance meant nothing.

As Bieber put himself lower in the mix, he knew it was because he needed to let us choose which part we cared about for his own self-preservation. His fluctuations meant everything.

As Shia sat in the dark, regressing through his personal history, he went back to a time when people sat together under the same darkness. And as it was ending, as he went back to modernity, he cried. His tears were mere noise. They meant nothing.

It ended in a sob, as it will.