Alex looks at The Wire again four years later, because he couldn’t wait the customary five.

It has been accepted as fact that we are currently living in a golden age of television. Nobody really talks about Dallas anymore, except to say that if that J.Lo movie version ever gets made, it is surely going to suck. The past decade has seen a number of shows that have been called some of the best television ever produced, and if you ask somebody what their favourite television show is, there are more recent options than ever before that won’t instantly make you think, “This is a person who probably thinks LMFAO is interesting and vital.” That there is probably only one acceptable pre-HBO choice left shows how massive the medium’s overhaul has been. But if you ask somebody what they think the best show that has ever aired on television is, there are two answers: either the person you’re talking to says “It’s obviously The Wire,” or they say something else, because they haven’t watched The Wire.

Since its series finale in March 2008, people tend to watch The Wire like they have a limited amount of time to finish it before their DVDs spontaneously combust. I haven’t been to a movie theatre in three and a half weeks and it’s all McNulty’s fault. Similarly, I haven’t shaved since the day before I started watching The Wire for the third time a few Sundays ago. I have a beard now, and it is purely because in the time it takes to shave, I can watch a Bunny Colvin monologue instead. The first time I watched the show in 2008, it dominated my life in a way few other media products have. I would wake up, watch a few episodes, and go to work at a video store where I would recommend The Wire to any customer that would listen. Then I would go home and watch some more, or I would play some video games with a fellow fan while we debated Tommy Carcetti’s law enforcement platform. I didn’t have the internet, and I didn’t have cable. Sometimes I would go out with friends, but I would always spend most of that time trying to talk to somebody about The Wire. These were more or less the only activities I partook in for a month, and judging by how often James has been texting me lines as he watches the show for the first time now, this is still the way the show is consumed by most people.

It has become clear to me that, as a result of the obsessive style of consumption The Wire seems to demand, I have possibly spent more of my adult life discussing The Wire than anything else. If you find out that somebody you are talking to has seen the show in its entirety, it becomes clear pretty much instantly that this conversation will go on for at least the length of time it takes to watch an episode of the series. While there are some aspects of the show everybody enjoys (Omar and Stringer Bell, mostly), there is so much in the show to like that invariably somebody will say something new. One might say they hate Brother Mouzone because of how unrealistic he feels, or perhaps somebody will say they like that character because it is one of the few times the show’s writers actively acknowledges that what they’ve produced is fiction. Maybe this person likes to posit a theory about how J.D. Williams and Reg E. Cathey’s pre-Wire roles in Pootie Tang have something to do with fellow awkward abbreviation fan Louis CK’s rise to prominence. And while most people who love The Wire do so because it is remarkably entertaining and manages to keep the viewer engaged pretty much constantly, the most common aspect to bring up is how the show always feels important.

One can’t read or talk about the show without discussing the elements of realism present in the show, or a feeling of import that generally comes with something that is both realistic, about social issues, and really fucking good. In a discussion with writer Nick Hornby, The Wire creator David Simon described that, “While [the producers] hope the show is entertaining enough, none of us think of ourselves as providing entertainment. The impulse is, again, either journalistic or literary.” In that same discussion, Simon also likens his show to Greek myths, which seems to be something David Simon does in most discussions. “We’re stealing from an earlier, less-traveled construct – the Greeks – lifting our thematic stance wholesale from Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides to create doomed and fated protagonists who confront a rigged game with their own mortality. […] But instead of the old gods, The Wire is a Greek tragedy in which the postmodern institutions are the Olympian forces.” Every character on The Wire is a product of seemingly immovable institutions, institutions that trap citizens and systematically continue Baltimore’s cycle of despair… Michel Foucault would have loved this shit.

Simon’s background as a journalist is certainly present in the show, as is the police background of his creative partner Ed “not the guy from The Brothers McMullan” Burns. Simon says of the writing in the show that, “I’m the kind of person who, when I’m writing, cares above all about whether the people I’m writing about will recognize themselves. I’m not thinking about the general reader. My greatest fear is that the people in the world I’m writing about will read it and say, ‘Nah, there’s nothing there.’” This quote more or less sums up the attempted feel of the show: perceived realism and basis in fact, as the show goes to great lengths to use what would be deemed authentic slang and that the police department reacts to a murder in a way that an actual police department would act. However, the show is obviously fiction. Chris Partlow doesn’t exist, as proven by the fact that Gbenga Akinnagbe appears to be possibly the happiest, most non-terrifying person ever interviewed. Omar can’t even whistle; a middle-aged woman did it in post-production. Former Baltimore Sun journalist and Wire writer William F. Zorzi has written that, “Story was always paramount, and that meant that no storyline was ever twisted or bent in order to squeeze in a ‘real’ character. If anything, it was the other way around.” While the show was meticulously researched and more often than not based around true stories and figures in Baltimore crime history, The Wire compressed somewhere between 40-50 years of stories into 60 episodes of scripted television; the line is blurred, but as Zorzi states, the story always mattered most. Fact was even changed in order to give a character a happier ending than their real life counterpart; the confidential informant that Bubbles is based on died of AIDS in 1992, as opposed to defeating his struggles with addiction in season five. Your favourite moment on The Wire was probably somehow based in reality, but it was still fiction.

Everybody has their favourite season of the show, with seasons three and four being the consensus favourites, and The Wire’s version of a “John Lennon vs. Paul McCartney” debate. If you like When I’m Sixty Four a lot, your favourite season of The Wire is probably the fourth, because you are a more emotional person who might cry while watching Ty Pennington build a house. Season three of The Wire, on the other hand, is the most abstractly polemic and interesting of the show, kind of like John Lennon rage fucking a stranger after Richard Nixon was re-elected in 1972. The drug free zone, or Hamsterdam, set up by discouraged Baltimore po-lice Major Bunny Colvin represents the difficulty one faces when trying to change the world they are in, a theme that continues throughout pretty much every plot line of the season. From Stringer Bell trying to move Avon away from his war with Marlo toward real estate, to McNulty’s vocalized confusion of “What the fuck did I do?” becoming a more internal dialogue of “What the fuck am I doing?” pretty much everything in the season is about the difficulty one faces when they try to make enact sizeable change. Hamsterdam shows this pursuit on a larger scale, furthering the show’s point that the war on drugs is doing more harm to society than good. And despite being the second most ludicrous thing the show ever did, the reason viewers bought into the idea of the free zone was because the arguments always seemed kind of sound. We know nobody would actually attempt to create Hamsterdam in real life, but Simon and company make it seem like something that maybe somebody should try. Season four is a remarkably interesting, ballsy and emotionally compelling entry into the show as well, but its more literal examination of the problems in the school system make it slightly less interesting (albeit debatably more engaging).

Contrasting this, while being adored by some, the second season of The Wire has been one of the more poorly received seasons of the show. The reason a lot of people don’t like the second season is because, when first watching the show, you don’t know that each season is going to be drastically different than what preceded it. When season two begins, you have no idea who the fuck this Frank Sobotka guy is, or why that Greek guy with the tiny coffee cup wears such ridiculous hats, nor do you know why any of this matters… at this point, you still thought you were watching a cop show. The people that do really like season two tend to be television critics and more writer-y type viewers, people who appreciate choices that go against the grain of what television writing is supposed to be. (If you’re talking to somebody who really liked Young Adult, chances are they like season two of The Wire as well.) On the second time through the show, most people like the season on the docks more, precisely because they’re now prepared for the sizeable shift the show makes after Avon Barksdale gets locked up. (This also prepares viewers for the similar change that occurs with the focus shifting to the kids while McNulty essentially disappears in the fourth season.) However, no matter who you ask, chances are that any given viewer thinks season five is one of the low points of The Wire’s run.

The most ridiculous thing The Wire did is clearly McNulty’s creation of the red ribbon serial killer. The writing staff’s decision to have him choke dead homeless people in order to obtain funding is rarely classified as anything less than “Robocop 3 bad.” But what makes season five interesting is that it seems to be the most removed from the rest of the series; while the first four seasons are ostensibly saying, “This is a reflection of a modern reality,” the fifth is saying, “This is how bad things could get in the near future if these things continue.” In the first episode of the season, Major Carver addresses his Western District officers and explains that the promises Mayor Carcetti has made throughout the department are going to be delayed for unforeseen circumstances*, Carver’s cops generally lose their shit and start screaming like an angry mob. Carver whispers to somebody that if the municipal government doesn’t get their shit together soon the department could lose these officers’ dedication for good. What season five then proceeds to depict in the police department is what could happen in the future if institutions continue to fail who they are supposedly meant to serve. By pairing this with the newspaper industry, which is at its lowest point and debatably on its way to death, The Wire contrasts the police department with an institution where these cutbacks are killing it, and implying that in the future perhaps the only way to do real police work will be to fabricate a serial killer to generate funding. “It seems absurd, but it will only seem crazy until it actually happens,” the show is saying. This is why Lester Freamon had to be in on the deal with McNulty. The show couldn’t depict its alcoholic, self-loathing, loose cannon character as the sole creator of the scheme; they had to use the most logical, best detective Baltimore has to illustrate that this type of institutional failure can influence any kind of person to act irrationally. Season five is probably still the worst season of the show**, but being the worst aspect of something that is almost always described as “the best” isn’t such a bad thing to be.

*The school system has a sizeable debt.

*The school system has a sizeable debt.

**It should also be noted that The Wire has been watched by a comparatively small audience, and that the people who have seen it tend to be more affluent and media-savvy. We see the world of the Baltimore Sun depicted almost as a caricature, because we know more about that environment than anything else depicted in The Wire’s run, and it becomes less interesting and loses some of the aura of realism as a result.

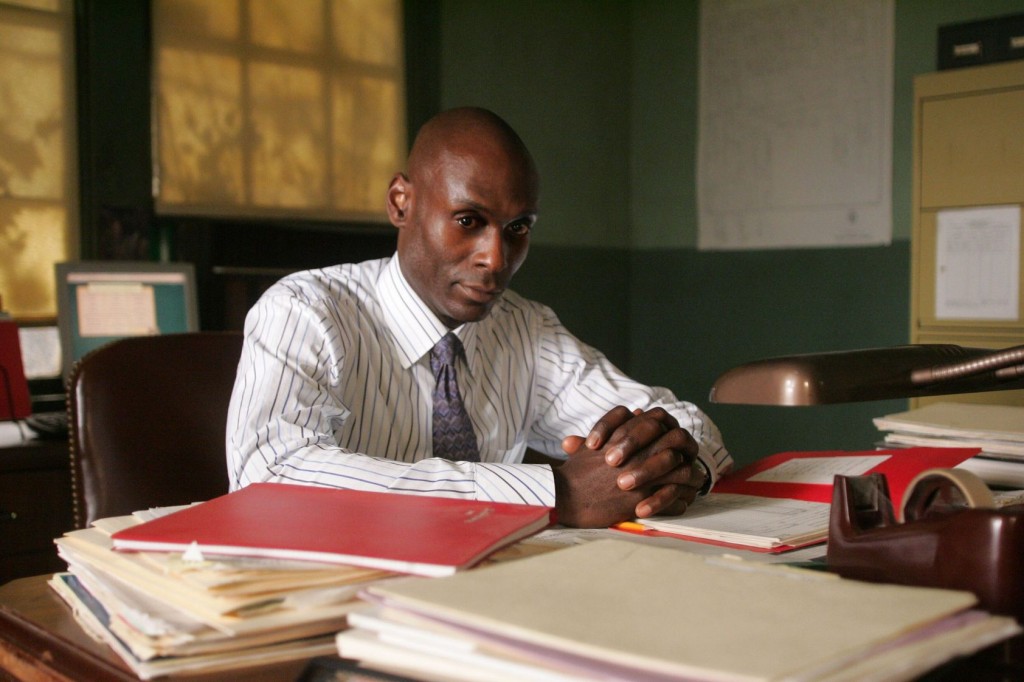

Like picking a favourite season, the discussion of favourite characters always comes up, as it will with any television show featuring more characters than god damn War & Peace. Universally, the two characters everybody gravitates to are Omar and Stringer Bell, because Omar is the badass we all wish we could be, and Stringer because Idris Elba might be the most charismatic motherfucker ever born. This is understandable, and it’s difficult to argue for anybody else as a favourite. While I love Kima Greggs’ voice and disposition more than anybody, even I know I get more excited when String is yelling at an assistant for taking minutes on a “criminal fucking conspiracy.” But one of the best things about The Wire is that its most enjoyable characters aren’t its most interesting characters. This is a difficult distinction to make, for myriad reasons. Stringer never had a chance to be the most interesting character, because the show continued for two seasons after he was killed, and we met so many new characters between his swan song and the show’s. And Omar, while having his distinctive code of morals, is a little too far removed from what the show is trying to convey, too far away from the system, to really be that interesting. Throughout the course of the show, the two most interesting characters are Bodie Broadus and Ellis Carver, something that was clear to me when I first finished the series in 2008, and only remains true as I rewatched it in 2012.

The point the writers of The Wire are trying to get at only becomes clear toward the end of the series’ run, although some of the more explicit hints at it come in the fourth season. We are watching a cycle in a city’s life, which is why the show goes to great lengths to make sure we recognize that all of the younger, minor characters are newer incarnations of McNulty and Omar as the show ends. We see Detective Sydnor become McNulty, Dukie becomes Bubbles, Michael turns into a less charismatic and less gay version of Omar, etc, etc. But with Bodie and Carver, we see two characters that are dramatically different when their arcs end as they were when the show begins, and characters that represent the whole arc of the show itself. Bodie, after the murder of Lil’ Kevin, becomes as fed up with the corner boy lifestyle as I was with watching Lil’ Kevin’s rub his hands together all the fucking time, and Bodie seems ready to take the stand against Marlo, Chris Partlow and Snoop Pearson for the murders that took place in the vacants. Of course, as we learn continually throughout The Wire, you can never break the cycle, and Bodie is soon killed.

Within the police department, Carver goes through a similar transformation over the course of the show. In season one, him and Herc are corrupt morons, taking money from a raid for themselves, and generally believing that the “Western district way” is the proper method of fighting the war on drugs. As the show continues, we never see Herc evolve from the self-centred, arrogant and generally loathsome person that he is at the beginning, and as the show ends he is appropriately vilified by way of brisket. As Carver’s arc continues, however, we see him go from being a slightly better person than Herc to some combination of Cedric Daniels and Bunny Colvin, the two characters who are probably the most moral human beings for the duration of the show’s run*. Since we are smart television viewers, we are learning about this world as the show progresses. And since Bodie and Carver are smart television characters, they learn about it, too. People often go to great lengths to say The Wire is a show about a city; in a DVD special feature, Clark Johnson says his favourite character is Baltimore. It kind of is, but it’s more about the life cycle of a city, which is told in various cycles, and the only way to really relate to the show is through its characters. We will presumably live through a variety of cycles in our lives, so the characters that have the most plausible and full arcs have to be the most interesting to us for the show’s ideology to really mean anything.

*I know Daniels did that shit in the Eastern district back in the day, but in Baltimore from 2002 to 2008, he was a pretty classy dude, with a voice/strut combination that would make the heroes of most Westerns jealous.

*I know Daniels did that shit in the Eastern district back in the day, but in Baltimore from 2002 to 2008, he was a pretty classy dude, with a voice/strut combination that would make the heroes of most Westerns jealous.

I somehow ended up working a contract job within the justice system for eight months in 2009, editing non-pertinent information about orgies out of otherwise pertinent wiretaps, and maintaining the courtroom technology throughout a major murder trial. I was basically Prez, except I never blinded a kid and I’m not very good at solving puzzles. I spent my time talking to a variety of cops and lawyers; I became friends with a Kima, a Maurice Levy who looked kind of like the villainous painting in Ghostbusters II, and I ran away from my version of Judge Phalen once because I was unsure of whether or not making eye contact with a judge constituted a mistrial. Shit, every day I handed headphones to men who murdered half as many people as Chris Partlow. I didn’t learn much I didn’t suspect before taking the job; I was grossly overpaid for doing fairly little, many of the defence lawyers were slimy assholes, and when I made a sound argument for changing one fairly small technological aspect of the process, I was repeatedly shut down without reason (to my endless frustration). However, it seems entirely possible that I would still be working there today if they had found a permanent position for me. The job was so simple, easy, and well paying that none of those things really bothered me. I was the problem, but the real problem was that nobody would ever really do anything about that.

If there is one thing The Wire does value, it is an individual working outside of an institution. As the series finale’s final montage shows, we will always fail if we are relying on an institution, but we can still succeed outside of it. At the end of the show, characters like Bubbles and McNulty find a type of happy ending: Bubbles overcomes his addiction and inability to talk about Sherrod in public, and McNulty begins to mend his problems with the loveable Beadie Russell, presumably to re-attain the happiness he found in season four. The Wire seems cynical, which it kind of is, but it is actually kind of optimistic, possibly more optimistic than many of its writers realize. One only has to look within the medium of television for proof: the rise in great, inventive, new styles of television is fairly recent, all things considered. This is a medium that has been in existence for over half a century that has undergone a considerable change. What David Simon and his crew represent is the spirit of McNulty; doing it within an established institution, but managing to be unique, interesting, and really fucking entertaining. And while the series might have existed on a channel with a smaller viewership than a network like ABC, its influence is widespread. Parks & Recreation is basically a comedic version of The Wire, and even iCarly parodied Snoop’s death. Simon might explicitly have been trying to convey the difficult nature of operating within an established system, but what his show implicitly got across is that it is possible to change something from within an institution. It’s not easy to do so, but if one really looks around, things aren’t as bleak as they might initially seem. There are interesting, vital voices out there, ones so worth hearing that people will temporarily retire from doing much of anything in order to consume them.

And now I’m going to pour a Jameson’s and shave my beard. I’ll be listening to another podcast about The Wire, but then I’m done. I’ll probably wake up and think about David Simon a little bit tomorrow as I clean up my pile of DVDs, but I assume that once I begin watching a new television show, I will have moved on. I’ll probably just start thinking about Don Draper and trade in the Jameson’s for an Old Fashioned. I would imagine I’ll watch The Wire again some day, and I’ll surely think about it when I get pissed off about poor institutional decision-making. But when I think of The Wire, it will always make me think about the possibilities of a medium I grew up thinking was far less interesting than film. In making The Wire, David Simon wanted to show how terrible institutions are – which he did – but he also showed that there is hope. He might not have helped to change his real city’s landscape, but his show is the best example of how television redefined what it can accomplish. And if the only tangible effects it has made is to get some of the show’s actors to start social programs or make a documentary about teenage homelessness, The Wire has helped television be taken even more seriously. Perhaps its ideas will be one day more accepted, but for now, its mere existence is still a good start.